Memoir of N.Frank Humphreys

reproduced from

archive.org

MISFIT

TRAVELLING STUDENT

CRAMMING FOR THE DIPLOMATIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INDIAN POLICE

STUDENT OF VEDANTA

AIRMAN

INTELLIGENCE OFFICER

JOURNALIST

FARMER

STORE MANAGER

POST OFFICE WORKER

SCHOOLMASTER

TUTOR

SECRETARY

CARPENTER

PUBLIC SPEAKER

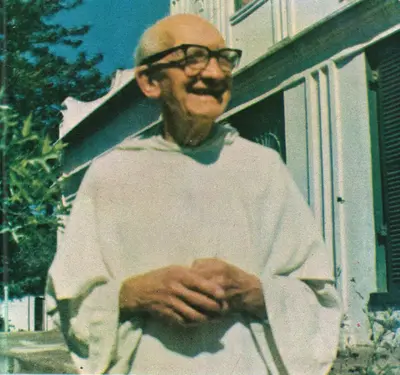

NICHOLAS (FRANCIS) HUMPHREYS, O.P.

DOMINICAN AND PRIEST

1927-1975

DISTRICT PRIEST COUNSELLOR

PREACHER LECTURER

WRITER PROPAGANDIST

The editors wish to thank the following for information contained

in letters, articles, etc.:

Toni Jansen O.P.

The Staff of St.Martin Centre, Stellenbosch

Alice O'Neill

Sister Colmar O.P.

Sister Dalmatia O.P.

Sister Leontia O.P.

FOREWORD

Fr.Nicholas Humphreys (or ‘Father Nick’ as we used to call

him) was indeed a phenomenon. Even a casual meeting with

him was an event. Living with him was an unforgettable event.

Even those who might have disagreed with him or his methods,

would have to admit that he was a quite extraordinary person.

There are so many stories about Fr.Nicholas, so many

memories. People of all races and all classes throughout the

length and breadth of the Church in Southern Africa can remember

something or other that he did or said or wrote or something that

others have told them about “Father Nick’. Those of us who

knew him a little better had always realised that his earlier life,

before he became a Catholic and a Dominican priest, had also

been remarkably eventful and indeed adventurous. The details

were known to very few.

Here at last in this little book we have the full story and

what a story it is! That any human life could have been packed -

with so much activity, so many illnesses, such a variety of expe-

rience and so much apostolic work is almost unbelievable.

However the real interest of this book and the real value of

Fr.Nicholas’s life-story is not to be found in the unusualness of

his activities, his experiences or his personality. The real interest

and value for the reader will be found in the spirit of this man

who, in his own way, struggled and battled to find God and to

do God's will and God’s work — this man who strove relentlessly

to be nothing less than a saint.

We are grateful to him for his example and we are grateful

to the writers and editors of this book for making his life-story

available to us.

FR.ALBERT NOLAN, O.P.,

Vicar General

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4 Foreword

7 Introduction

12 1890-1910 Childhood and Youth

17 1910-1919 Indian Police — Flying — Intelligence

22 1919-1924 South Africa

29 1924-1927 England — Leysin — Rome — England

32 1927-1931 Dominican

36 1931-1948 Stellenbosch — Springs — Potchefstroom

44 1948-1958 Springs — Boksburg

49 1958-1975 St.Peter’s Seminary — St.Nicholas Priory

“And so the long struggle upwards from a deficient Christianity

— however well meant — through being a quasi-prophet of non-Christianity,

to the Home I have been given in the Order, has brought me to the point

where I have been asked to teach and explain the personal dealings with

the soul of the One Whose ways I have been watching and struggling to learn

during the whole of my life.”

– Fr.Nicholas Humphreys [p.53]

NICHOLAS FRANCIS HUMPHREYS, O.P.

1890 - 1975 A MEMOIR

INTRODUCTION

Fr.Nicholas Humphreys wrote an autobiography in the early

1960's at the request of his Dominican religious Superior. He

called it 'A Trivial Tale’ and of it he wrote:

“I have not at all wanted to do it, but obedience is obedience,

and so, after some years I am starting it. It is true my life has

been full of events, but they have been relatively smalf ones, of

interest only to myself, in that, in reflecting on this I can wonder

at the love of God and his care even for the smallest. “Dominus

sollicitus est mei’ (Ps. 40:18), ‘the Lord is full of care for me’.

This line carried me through my Novitiate at Woodchester and I

can see that it has been true all my life. So He is for every one

of us, and so, in telling my trivial tale, I shall have the happiness

of acknowledging to Him His goodness, His solicitude, and my

own wonder and gratitude over His unfailing and detailed care.

I shall be continuously singing of His goodness, whether I mention

His name or not’.

The manuscript which Fr.Nicholas typed is a narrative of his

life from his earliest recollections as a child until the period in

the late fifties and early sixties when he was Spiritual Director at

St. Peter’s Seminary, Pevensey, Natal. it is this document which

is the basis of this memoir and quotations will be from it unless

otherwise stated. As far as possible, Fr.Nicholas will be allowed

to speak for himself.

He ends his story on the same note with which he began:

“I can only marvel at His kindness and the perfection of His

Providence. It is all His Gift. Who could doubt His Love and

Care. I end with the words that carried me through many an

early difficulty: ‘Dominus sollicitus est mei’. I cannot begin

to thank Him.”

The tale which Fr.Nicholas tells is indeed “full of events”,

Many of these events were concerned with his health. He had

more than twenty five serious operations during his lifetime. His

illnesses included septicaemia, typhoid, a cyst, pneumonia, heart

strain, bronchitis, pleurisy and tuberculosis. He had a broken

nose twice, two arm breakages, his appendix out, varicocele, a

spine injury and a spinal abscess, three operations for glandular

T.B., face bones broken ina plane crash, two operations for haemor-

rhoids, a kidney removed, jaundice, skin disease, cardiac asthma,

hernia, TB lump, gall bladder, two operations on his nose. He

spent about seven years in hospital at different times. He ended

by breaking an arm at 57, ribs at 79, both legs at 80, and a hip

and thigh at 82.

He had a most varied career in spite of ail this, beginning by

cramming for the Chinese Interpreter’s examination, changing to

the Indian Police, later he joined the Royal Flying Corps. He

Studied journalism and Russian while ill, joined the Intelligence

Service, was engaged to be married, farmed in the Sundays River

valley, worked as a store keeper and farm manager, in the Post

Office at East London as a sorter, was secretary to a Swiss

doctor, tutor to the son of a rich American. He tried to become

a Carthusian, a Jesuit and a Salesian but eventually became a

Dominican. He ran a joinery business, and belonged to the Catho-

lic Evidence Guild. After becoming a Dominican he was ordained

at Stellenbosch and spent a large part of the rest of his life build-

ing up the Mission at Potchefstroom. After this he was chaplain

to a convent, Spiritual Director to African students, and in the

last part of his life, dedicated himself to the St.Martin Centre.

He wielded his pen throughout his life writing on his Mission

experiences and on social and educational matters.

Until he was nearly thirty, Francis, as he was baptized, would

have scarcely called himself a Christian, although his parents were

Anglicans. He was much influenced from childhood by Spiri-

tualism and Occultism to which his mother introduced him, and

also later, by Vedanta philosophy. While he appreciated the higher

flights of the latter and gained much from it, he regretted the

negative elements which affected his life and the influence of

Occultism in particular. Looking back he saw the hand of God's

Providence in bringing him into the Catholic Church and then into

the Dominican Order and he was always filled with wonder and

thankfulness.

At the same time, in his reaction to the negative attitude to

life which had governed him for long, he was led to stress the

importance of thinking about things positively and positive action

in work, He must co-operate with Providence: time must be

redeemed by hard work, and other, more negative people, must

have their ‘wills fortified’ and pressed into service. Many of his

brethren would find themselves holding the other end of a plank

while he worked on it! Many will remember his saying: ‘Marry

your circumstances’.

He combined a simple faith and wonder with an_ unfailing

drive to work, to adapt to the situation and to exploit it for good.

This also appeared in his attitude to people. He saw always

the good behind the bad and had a great appreciation of character.

While he was sad when people let him down, he readily excused

them or made light of the situation. He had his own personal

methods but tried to adapt to others when necessary. After

standing in for one of his brethren at a Mission he remarks at

the end of the period:

“I handed over... and he, poor fellow, had then the task

of going through my accounts, item by item, and re-editing

them by his system, for in many places I had not fully grasped

his mind, and in the matter of accounts, no matter how exact

the rules, every accountant, like everyone else in a trade —

including apparently sometimes Canonists — prefers his own

interpretation.”

Although the Autobiography shows him as very serious

minded, he had nevertheless a good sense of humour and many

were the jokes he enjoyed with his brethren. His criticism was

governed by charity and humour although he could strongly con-

demn what he saw as wrong or unjust.

He had an unfailing love of the black peoples of South Africa

and he spent most of his time in their service from his time in

Potchefstroom until he set up the St.Martin Centre in his old

age. He was fluent in SetSwana and Sesotho end learned some

Zulu when he was over sixty. He saw the course of events which

was developing in South Africa very clearly. During a conversa-

tion in Cape Town in which an Afrikaner was saying, as he records,

“In the European manner, ‘that we should do this and that

for the African’, adding that, "in his opinion the English were

the trouble and did not know their language and so forth’,

Nicholas intervened:

“You know, talk like that makes me feel that you Afrikaner

people are ten years out of date.”

Asked what he meant, he replied:

“that they did not know the mind of the African today. I

said I had been twenty years with them and spoke Sesotho,

SetSwana and Zulu, that the African people had reached a

point when they were not going to be anyone's fools much

longer. They did not yet know just what they were going

to do about it, but the change of mind had come about and

it would not change back. Ten years before they still took

it as in the nature of things that they should serve the white

man, but that phase was over and would not return,”

This was in 1955 and, after noting that many people did not

think the African was getting a fair deal but feared to say so, he

wrote:

“Meanwhile the African goes on quietly, reserved, poker-

faced, hiding his feelings, and the European does not suspect

the, as yet unformulated, urge that is going on inside,”

Although one may detect traces of the imperialism and pater-

nalism of the British Raj in India in this, one can sense that Nicholas

had the humanity and freedom of the African at heart.

Nicholas started in Journalism during the first World War

when the ‘Daily Mail’ asked him to write some articles on his expe-

riences in the Royal Flying Corps. in his priestly life, writing was

part of his apostolate. He published many stories from the ‘Mis-

sion Field’ and on education and social problems in the ‘Southern

Cross’ newspaper and eventually published a collection under the

title ‘‘Missionary in South Africa”. As he said “people illustrate

events” and his stories about people illustrate their personalities.

He paid constant tribute to those with whom and for whom

he worked. His Autobiography is, indeed, his story, but contains

many stories about the people who touched his life in various

ways. Stories illustrate humanity, providence, strength, weak-

ness, among other things. His trivial tale shows his humanity,

but Nicholas, as he said, used his own story to illustrate God's

Providence. Harvey Cox notes that the story element in religion

tells use the whence, the whither and the how of life. (Seduct-

ion of the Spirit, Preface). Under the form of ‘witness’ or ,testi-

mony’ it is much used by evangelists and is kin to the parable.

It shows us how God works within the history of people. Nicholas

in his practical way tells us stories that we may know about God.

His Autobiography tells us his story that we may know that God

is full of care for each one of us.

The Autobiography is divided into two parts, the first con-

cerned with the period up to the time Francis became a Dominican

and took the name Nicholas, the second records his life as a

Dominican until the early nineteen sixties. Other sources have

been used for the period after that.

CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

1890 - 1910

Francis Henry Humphreys was born on the 17th May 1890.

His father, of Irish, French and English extraction, was a doctor

practising in London. After changing from general practice to care

of the mentally sick, he soon lost his patients and had a hard

struggle. His mother was of Irish, Scottish and French descent.

He had one brother and one sister, four and three years older

than himself respectively. The illnesses which punctuated his

whole life began early. At seven he had blood poisoning and

diphtheria at eight.

The three children were brought up at first by a governess,

a High Anglican like his parents. Francis, it appears, had learnt

to read and write and do simple sums by the age of four, and

on his fourth birthday his governess told him he would begin

learning Latin. At the age of ten he went to the Kings Choir

School at Cambridge, since he had become unmanageable by

his governess. He stayed there for about eighteen months, after

which he was sent home. Although he thought the reasons for

this untrue, and unjust, he admitted that he was an odd and

unsatisfactory child, which he attributed to the fact that his mother

practised Fortune Telling, Table Turning, Second Sight and later,

Spiritualism.

Later in life he was grateful for the influence of his governess,

but at eight years old, he and his sister visited his mother’s latest

Fortune Teller unknown to the governess. In the crystal bail,

the Fortune Teller said she saw a bridge. Francis said he saw

half a bridge and she agreed. That was all, but later Francis,

who considered he had some sort of hyper-sensitiveness, saw

himself stepping onto a bridge which led nowhere. In his book

he remarks of such matters:

“Fortune Telling etc., have a strong tendency to develop a

subtle form of pride, lying and vain glory, injuring the develop-

ment of the intellect and developing undue dependence upon

imagination.”

He saw the effects later on as the work of Satan and the

interest produced in him interior lying, vanity and opportunism.

This affected him for twenty years. So his story is largely about

the “messengers of goodness’ who brought him to something

different which he had begun to experience in the ideals of his

Anglican governess.

Later in life he wrote of his mother:

“Well, poor dear, she had a hard time trying to make ends

meet and in this continual and exhausting struggle she showed

marvellous courage. I remember once she was so worn out

that she only stopped throwing herself out of a window when

she was half way through it. Perhaps the devil of occultism

was behind that action and only her real goodness saved her.

She was always planning and working for those around her

and within seven weeks of being 91 she was going on foot

up and down the mile to town twice every day at full speed

doing things mainly for other people. I remember her first

thought on receiving a present was always ‘Now who can I

give this to?’ I am thankful to have had such a Mother and

her mistakes count for nothing beside her goodness. Yes,

Almighty God looked after her.”

She was killed by a car in the blackout of 1945. it is interest-

ing that Francis himself in later life used to label presents in case

he should give them away to the donor!

After Cambridge, Francis was sent to a school in Essex where

he did not stay very long. Of his experience he says:

“As a boy I was never afraid to fight with my fists, but short

of that I was completely incompetent: anyone could bully me

and order me to do ridiculous things and everyone did. This

too I blame on the kind of negative attitude of mind that the

‘occult’ sciences had bred in me. Its training was the reverse

of a positive view of life, of the use of one’s brains in reasan-

able self-assertion.”'

At this time he had a private tutor named Arthur Wilson who

was a cripple. Francis had a happy time with him for “his poise,

patience, courage and simplicity of heart” left an indelible impres-

sion which was valuable later when Francis had to lie up for long

periods. About this time he had a piece of bone removed from

the tip of his nose which had been broken in a fight.

In 1905, at fifteen, Francis was sent to Cranleigh to school.

During his first summer holiday he taught English for two months

to the children of the Lombardon family in Aix-en-Provence in

France, having already learned a good deal of French from his

governess and from his mother who spoke it fluently. Francis

was really happy in France for the first time in his life. The

family took him to Mass although he did not understand what

it was all about at the time. He made friends with a priest Pére

Fillatre who taught him French and Latin. He was given the

‘imitation of Christ’ to translate from Latin.

“What an opening out that was from the cramping cold,

solitary life I had lived, even at school, where I never managed

to keep friends for long — that occultist twist came to make

me an undesirable companion.”

For the time being the ‘kink’ in him was dissolved in the

atmosphere of Provence and the solid Catholic culture of the

family:

“I could just be happy and natural without delusions of secret

greatness, while I told silly little lies to support the illusion.”

it seemed to him that:

“contact with Catholic culture was bringing a positive use

of intelligence to light, and countering the negative attitude

induced by the evil of occultism.”

One may think that Francis looking back exaggerates his

weaknesses but certainly his reaction against occultism must have

had a great deal to do wtih the forming of his character with its

strongly positive and active attitude to life.

Pére Fillatre was also a great help to him and he visited him

again later on: :

“a personality who was sure.of himself and humble, sensitive

to atmosphere, magnanimous and generous, something that

only the foundations of a Catholic culture can produce, When

I want to think of courage in affliction, I recall Mrr. Arthur,

but when I want to think of a fully formed personality, there

stands Pére Fillatre.”

Francis left his public school sometime in 1905 and was put

in for the Chinese Interpretership, an entry into the Diplomatic

Corps. For this purpose he went to Lobberich in Germany in

1906 where he stayed with a headmaster and his family, Catholics

who scarcely practised. He was happy there, loved the singing

and music and fitted in with the German boys better than he had

done with the English. He revelled in the Gymnasium and foot-

ball. He took a correspondence course, at the same time, for

the Student Interpreters with Kings College, London. He was

much impressed by the way German boys studied. Here again he

found "the friendliness of ancient, well-established Catholic cul-

ture’. At that time he found the Germans were obsessed with the

idea that England planned to attack Germany.

While in Germany, he took a trip down the Rhine and visited

Cologne, Coblenz and Wiesbaden where his father had been at

school, This was “a marvellous trip and my whole life was

renewed”. He spent the summer holiday with the Lombardons

and returned to Germany by the French Riviera, Genoa, Milan,

the Italian Lakes, Switzerland and over the Furka Pass to Gletsch

and back to Lobberich. After another trip up and down the Rhine

he returned to England at the end of the year.

In England he studied at Kings College London to enter the

Student Interpreters in China. During this period his home life

lacked order; worry and poverty and the influence of occultism

played havoc with him. He broke his right leg twice that year.

Since there had been a change of age for those entering the Stu-

dent Interpreters, his coaches advised him to try for the Indian

Police.

“I had reached a point where the general situation was

becoming unbearable and I tried vaguely to find some plan

which would make for a change and a life where study would

be better served.”

As a result he was sent in January 1907 to a crammer in

Folkestone but after a month fell ill, had two operations and eight

months illness. In the autumn he was back at Folkestone where

a student called Whistler taught him how to study and he had

no further difficulty about an ordered life — so long as he was

not at home.

During this year he visited Lourdes with the Lombardon

family where he joined in the Hail Mary, saw many cures and

took part in the torchlight procession.

“Perhaps it opened the way to the Conversion which came

twelve years later, and maybe it earned the great grace of

friendship with Hugh Whistler.”

INDIAN POLICE — FLYING — INTELLIGENCE

1910-1919

Francis passed the Police examination low on the list. Soon

afterwards he went down with pleurisy and other internal troubles.

His examination result was due to ill-health all that year. His

papers included French, German, English, History. After nearly

dying, he sailed for India on 31st December 1910. He does not

record anything of the period between 1908 and 1910. During

the voyage he developed pleurisy again and on arrival in India

went into the Bombay Hospital where he nearly died. He also

caught malaria there.

He was then posted to Velore but spent two months in the

hill country recuperating. The horse he rode had the habit Of

taking a short step from time to time and this started the’ back

trouble which lasted throughout his life. At this time he got a

motor cycle.

One important contact came to him through learning Telegu,

one of the local languages. This was acquaintance with Narasi-

miva, the Telegu Munshi. In Folkstone Francis had shaken off

Spiritualism for Theosophy which had a Hindu basis. Narasimiva

was an educated Hindu Brahmin but knew also the Vedanta ideals

which Francis was seeking to realise. Narasimiva was interested

in the mysticism behind Vedanta philosophy and something far

beyond Yoga. Another Indian he met was Ganaphathi Sastriar,

a travelling lecturer in the higher flights of Hindu philosophy.

After passing his first examination in Telegu, Francis was

sent to the Anantapur District and, after some training, was sent

to Kalyandrug to gain experience as Acting Inspector, where he

had six police stations and about one hundred men under him.

“Frustration, boredom, overwork, blistering heat, malaria,

uncertain subordinates and Telegu, morning, noon and night,

and crime of which one could make neither head nor tail,

and a good deal of it was a matter of a goat stolen by some-

one who was starving; this was one’s daily life lived in lone-

liness.”

In due course he was promoted to the sub-division of a

District, a black spot on the crime map of India, where he had

nine murders, a threat of riot and the discovery of a large gang

of bandits, in one week. This more difficult side of life in India

was offset by the traditional sports and social life under the

British Raj, for example, shooting and polo.

About this time his cough grew worse and tuberculosis was

diagnosed. After two and a half years Francis returned to England.

Back in England he developed a large swelling in his back,

but his cough improved. He stayed with his parents at a guest

house-nursing home, Bayliss House near Slough. He was soon

in hospital in London for an operation for an abscess in the sacrum.

Back at Bayliss House he was told to lie flat for six weeks, but

a Doctor who was organising a party in the Highlands said he

would be better walking about. So Francis went to Scotland

for three months where he attended the Northern Meeting Ball

at Inverness and visited the Orkneys and Shetlands.

On his return to London with his back much worse, he began

a liaison with a certain woman thirty years older than himself.

This was broken off later for two years and then resumed for a

while.

During this period Francis wrote a good deal, practising

journalism but nothing was published. He studied ‘Popular

Science’ also, making notes for a National Health Scheme. He

began to learn Russian and practised it with refugees at the

beginning of the Great War, becoming fluent in speaking and

writing it.

The wound in his back healed and he got up for a time,

but after six weeks the pain and swelling returned. He had had

twelve doctors and the verdict was he would be a cripple for life.

Fortunately at this time he found an osteopath, Johnston May,

and, after manipulation, got much better.

After six months, during which he was treated by the osteo-

path, he was passed for flying and commissioned towards the

end of 1915. He was able to lead a “moderately normal life’

although for the rest of his life he would ask people to pull the

‘kink’ out of his back for him by pulling at his head over the end

of a bed, or even by standing on his back.

In January 1916 he began flying instruction at Northolt after

two weeks drilling at the Curragh in Dublin. His brother was

already a pilot and through him he got into the Flying Corps.

Before he could start his training he went down with TB

for six months, but in mid-1916 he was learning to fly primitive

‘Short Horns’ and ‘Long Horns’ at 60 mph. Later he flew Avro

machines and ‘Elephant’ Martinsydes. In the winter of 1917

he was sent to France and joined 27 Squadron at Doulens, The

fumes of the Martinsydes’ exhausts soon gave him bronchitis

and he was sent back to England.

After convalescence, he was invited to a party at Buckingham

Palace where he was presented to King George V who mistook

him for a Canadian and to Queen Mary who asked him if he liked

flying. As a result of this party he met a Mr Bowhay who began

to talk to him about mental processes. Francis found that his

remarks struck home after a while:

“You mean that I have never thought for myself in my life,

but lived by rules and other peoples’ words?” ‘Yes’, Mr

Bowhay replied.

This was a revelation to Francis and he saw that his negative

mind was being brought under the treatment it needed.

About this time Francis wrote an article about a bus journey

which he took to the ‘Daily Mail’ offices where he asked for the

‘Chief’ and was shown into Northcliffe’s office. Although this

article was not published, he was asked to write some articles

on his flying experiences which were published. During an enquiry

about his right to publish these accounts of flying, it was dis-

covered that he knew Russian and other languages. He was

posted to the GHQ at the Horse Guards to learn Intelligence

work. He worked at this for nine months, questioning prisoners

from Germany; preparing a circular showing the different types

of aeroplanes for the use of the Air Defence, and charting the

route of enemy planes for the gunners.

About this time the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval

Air Service were amalgamated into the Royal Air Force and made

into a separate arm with its own HQ and Intelligence. Francis

was sent to the new Command but then sent back to the War

Office to copy out their Card Index. Of his preparation of the

circular and what he learnt through it, he writes:

“I had to tour round so many Offices to get the information

I needed. It needed incessant patience and tact to get what

I wanted, and it was marvellous training in interviewing offi-

cials and in getting people to give up necessary material that

they did not want to yield! I learned too to carry a book round

with me to read while waiting for someone else to finish his

interview. it helped one to keep cool!”

Both his art of persuasion and his carrying round of a book

survived into later life as many of his brethren had reason to

know.

After this he went down with severe influenza and when he

recovered was sent to Salisbury Plain to do ‘light duty’ on a

training Aerodrome. After doing the job of recording hits for the

gunners, he got back into flying and organised a new flight

specialising in gunnery training. Once more he went down with

influenza.

While he was posted as Flying Instructor, a pupil took off

under him as he was coming in to land and he crashed his plane.

His top jaw was broken into four pieces, the antra were pushed

into his eyes, his nose was crushed. This was the end of his

flying. Ten months in hospital “made him respectable again’

and the sister remarked:

“Well, thank goodness, you are a bit better looking now than

you were before the accident.’

This crash wrought a further change in his negative attitude

and he studied Jevon's ‘Logic’ with Mr Bowhay. He realised he

had never put his mind to flying. He asked Mr Bowhay: ‘What

is the difference between Vedanta and Chrstianity?’” Mr Bowhay

replied:

“Broadly speaking it is this: Vedanta claims that everything

is from yourself, Christianity teaches that everything is from

outside you.” ‘This reply”, Francis remarks, ‘worked a

revolution in me. 1 became a Christian again.”

This accident happened in October 1918 and Francis lay sick

in hospital in London during a hard cold winter. After ten months

the splint and ‘antennae’ on his jaw were removed and he entered

a Convalescent Hospital at Bournemouth. He had been rushing

around London trying to raise gratuities and managed to raise

£1 000 including his savings. So there was a question now of

what he should do ‘in the great peace”.

A fellow patient said he was going to grow oranges in South

Africa and Francis read about the Zebedelia Orange Estates and

was very much interested. However, he was put off this project

and sought to buy land in the Sundays River Valley. As he needed

more capital, he found a partner in a man called Richards who

had farmed in New Zealand. Francis left for South Africa in

July 1919 when he was 29 years old. Before he left he met a

young girl, a Catholic, and there was an unspoken engagement

between them. Her father disapproved and Francis said he would

take up the matter again in two years time when his situation

would be different. After demobilisation from the Air Force he

sailed for South Africa on the ‘Umzumbi’ which took 28 days to

Cape Town. From there he took a train to Port Elizabeth.

SOUTH AFRICA

Francis and the Richards’ family began farming on a bare

piece of land in the Addo district. They had so far paid one fifth

of the price asked for it. They lived in a marquee, sleeping on

straw. The area was a river bed which had been cleared of prickly

pear, a place where elephants had roamed and the hunter Major

Pretorius had hunted them. There was a more or less continuous

South-East wind and only a trickle of brackish water available.

There was in fact a drought which lasted for three years and

building was impossible without water. Someone remarked that

‘they had bought in Faith, come out in Hope and seemed likely

to end by living on Charity’.

Water was brought by train to Addo and then on by ox

wagon. The group of four got 100 gallons every two weeks.

They set about building a house for the Richards family and the

land had to be laid out for irrigation. At this time Francis described

himself as a ‘moderately good carpenter’ and Richards could lay

bricks although these were in short supply. When their tent

blew away in a gale they lived for a while in a garage, which they

had built, until the house was finished, Meanwhile a contractor

laid out the land in ‘beds’ and another put up a fence and they

waited for the rain. Water did come down in the river but

six months hard work and 2000 lbs weight of beans brought

in only £15. The hot wind destroyed 1500 tomato plants and

bariey was badly planted and wasted.

In view of their needs Francis took a job as a storekeeper

and after two months another job as a carpenter and manager but

after another two months he returned to Engiand.

The reason for this return was to settle the matter of the

girl he had met before he left England. Francis had received a

cable from her mother saying that the engagement was now per-

mitted and that the girl would be brought to South Africa in

September 1920.

With his previous liaison and the thought that the country

would be too harsh for the girl, Francis was in considerable per-

plexity. The girl's parents had promised money and help for fur-

niture so that they could be married about a month after her arrival,

so Francis went to England to sort things out. Although the

engagement was not entirely sorted out, the other liaison was

finally broken off altogether. Francis was introduced in England

to a Jesuit, the uncle of the girl, and in a two hour conversation

he cleared up certain general problems about Christianity. Francis

read “Faith of our Fathers" and “The Threshold of Christianity”

and, as he started reading the latter on the journey from London

to Bournemouth, “the revelation came” as he puts it:

“I suddenly found myself saying: ‘I have no right to decide

these things for myself! No RIGHT!’ By Grace I had suddenly seen

the Church. I went over the moment again and again seeing it more

and more clearly.”

He returned to South Africa by the East Coast calling on the

Lombardon family from Marseilles and telling them he was going

to become a Catholic, On the boat he found a White Father,

Bishop Sweens, aboard and the latter gave him religious instruction

in French for three weeks.

In the Red Sea Francis had heat apoplexy and nearly died.

A Catholic man gave him a Rosary and as he did not know how

to say it, Francis invented his own way which took an hour and

a half:

“I was so enthralled with the Faith and with the beauty of

Our Lady, that I would have happily made it longer if I had

not been too sleepy.”

From Beira he returned to Port Elizabeth by train taking five

days and nights. ‘He was too hard up to buy food and begged

bully beef from the steward.

On his return he found that Richards was working as a depart-

mental manager and had paid off their debts. The day after his

return he had a cable from his Fiancée’s mother offering him a

job in italy, The parents would settle them there after their mar-

riage. Francis accepted this offer and, as he already knew a

fair amount of Italian, he decided to go to Cape Town and try

to get in with an Italian family.

After getting lodgings in Cape Town with an Italian family,

Francis called at the Catholic Cathedral Presbytery and was sent

to Fr.Hartin at Somerset Road Church for instructions. Three

weeks later his fiancée arrived with her parents and they drove

up to the Church and Fr.Hartin baptized Francis conditionally and

received him into the Church.

“I remember well my one thought: I have come home at last", he wrote.

In Port Elizabeth the girl's father set out to break up the

contract binding Francis and the girl and her mother urged him

to get a job. So he became a letter sorter at the Post Office. A

certificate of satisfactory service is extant. When he came home

from work a week after he started, he found the whole family

had cleared out. The girl later made an unhappy marriage and

was separated from her husband, Francis found them impossible

people, but he noted:

“I was the product of my background of occultism and Vedanta, and

of the opportunity they had given for the development of grave

personal faults.”

Francis’ behaviour in suddenly going to England, accepting a

job in Italy, shows a certain impulsiveness and perhaps some

confusion. He seemed, as later with his vocation to religious life,

to keep several options open. Perhaps he was undecided because he

could not yet clearly see his way. It is interesting that soon after

his conversion he began studying the 'Summa Theologica' of St.Thomas.

He may have had the idea of being a priest while still having hope

for his engagement, which was half cancelled.

Francis had to cancel the marriage arranged in Port Elizabeth

but, coming from the Church, he met a Mr Bradshaw, an accountant,

whom Fr.McSherry had told to look him up. Francis had received his

first communion with his fiancée in Port Elizabeth and had attended

some Mission services. Now Mr Bradshaw began to show him what he had

still to learn. The first thing to which he introduced Francis was

the English translation of the Summa of St.Thomas and Francis found

a new world opening out to him. He also lent him the Confessions of

St.Augustine and the life of St.Ignatius of Loyola. Francis fastened

on the idea of making a retreat and wrote to the Jesuits at Dunbrody

about it. On their advice he got a copy of the ‘Exercises’ and, while

still working at the Post Office, he worked solidly at the ‘Exercises’

five hours a day for a month in his spare time.

Francis worked by “going slowly step by step and repeating and

co-ordinating and beginning for the first time to see Christianity as

a whole, and marvelling at the joy of it.”

To a passing priest he remarked: ‘Father, this is wonderful,

it all rings true!’ ‘Naturally’, he replied, “for Catholicism is

founded on the nature of the human heart as it really is.”

“That was the whole point’, Francis commented, ‘that was why occultism

and Vedanta had led me astray. Now I was working to get my soul

straight. Indeed I began to see that word ‘straight’ in a fuller sense

than I had ever known, and the great virtue it takes to be what I called

‘ordinary’. I think I meant ‘normal’ in contrast with the ‘pride and

oddity’ that goes with occultism.”

Reading St Augustine's Confessions he wrote:

“I wept my heart out over the revelation of my own folly and the wonder

of God's goodness.’ He poured himself into a large exercise book taking

Ignatius point by point as he gave him “‘the key to human life and

conduct and the testing ground of my past’. I found myself even writing

in the style of St Augustine.”

Francis searched back into the past:

“for the key to find where my life had started to go wrong, and always I

came back to that fatal visit to the Fortune Teller... when something of

‘second sight’ appeared in me.”

Mr Bowhay had told him such powers were unhealthy and Francis found:

“I had been living on what reached me through that unhealthy measure more

than on the guidance of objective observation and reasoned consideration.

Unwittingly I stultified reason for the benefit of whatever malign guidance

might reach me from elsewhere and now was paying for it in the collapse of

my affairs, in the trouble brought on ... whom I loved dearly and whom I

had handled most carefully that no harm should come to her through me. Now

through St.Augustine and St Ignatius the whole scene was becoming for the

first time visible.”

Although he had thought the girl’s parents had handled the matter badly,

they had excuse and now he had the chance through Mr.Bradshaw and the

little Grey Books of Pelman to get things straight.

Since he had not started in the Post Office Service as a boy, he was warned

that his employment was only for three months. Someone suggested he become

a schoolmaster, which he had always looked upon as the world’s worst job.

However he applied and was accepted as a teacher at Weston in Natal. Here,

the Headmaster, Mr.Bates “grasped my trouble and helped me to develop my

vocation and obtain with it an established position. He was like a father’

A colleague also who had tried to be a student for the Church was able

to help him to a sure footing in the Faith. It was he who made Francis

think about studies for the priesthood, that priesthood he had seen

exemplified in Pére Fillatre, Bishop Sweens and priests in Port Elizabeth.

The foundation for this thought had been laid in Port Elizabeth as he

knelt in St Augustine’s Cathedral. He realised suddenly that his

fiancée was gone for good. It was a staggering blow and he cried out

in something like despair:

“All right, Lord, take her, but be good to me for she is all I've got.”

“Then something happened. I heard clearly a direction: ‘You must choose

Me’. [I replied, ‘I cannot, I have not got it ‘in me to make such a

choice. You must make me choose’. Again came the direction: ‘Choose!’

I replied again in the same way and the direction came a third time.

A third time I replied in the same way and then felt a terrible blank,

some Presence had departed from me. I cried out in despair: ‘All right,

all right, I choose, I choose!’ A little consolation returned but it

seemed far away.” :

Next day he asked if the Jesuits would accept him, but it was obviously

too early for that and so he returned once again to recovering his

fiancée. He was still very confused and divided.

At Weston, Francis learned to teach by watching other teachers. This

school was a Government school for the children of farmers and half a

day was spent in school and half a day on the farm or in the carpenter's

or blacksmith’s shop or elsewhere. Francis took the Teaching Certificate

Course second grade. He had to do four years work in nine months, so he

read and mastered a chapter a day of the set works until within three

weeks of the examination. He passed sixteenth out of eighty

candidates and received a Temporary Certificte. He had to do

another two years to get a iull Certificate.

He spent Christmas at Greytown making a retreat with Fr. van der Lanen

who was also chaplain to the Oakford Dominican Convent. Years later,

Mother Ignatius told him that she had prayed for him by name every

night since his visit, that he might become a priest.

At the school Francis was put in charge of the Cadet Corps and went on

training courses to Robert’s Heights (now Voor-trekkerhoogte). Here he

met Dr W.P.de Villiers in the winter of 1922 and they became fast friends.

After he returned from a second course at Voortrekkerhoogte, he found

he had been transferred to a nearby school en route for a Secondary

School post. But he was already ill with TB, an illness which would

last for three years.

About this time he heard that his fiancée was soon to be

married. This stunned him and he burnt her letters. He later

told his priest that he was free and would like to try and join the

Jesuits. The priest said “Why go so far? You are too old to

take their long course. Why not go and see the Dominicans just

up the line at Newcastle?’ So Francis met Fr.John Dominic

Rousselle who recommended him to the Provincial in England,

Fr.Bede Jarrett, who wrote to Francis. Francis was amazed at

how much could be said in a few sentences. Fr.Bede told him to

wait a year and collect money for his keep as a Novice, Francis

settled down gratefully to the idea of the Religious life ahead.

IV

ENGLAND — LEYSIN — ROME — ENGLAND

1924 - 1926

Because of his sickness Francis was taken to Grey’s Hospital - and

lay there until mid-December getting no better or worse. Then

he saw an advertisement for excursions to England for 19 days for

£35 and the doctor let him go. On the boat he lent a woman a

history book by a Catholic and she asked for more such books.

She later became a Catholic and Francis describes her as “his

first convert”.

On his return to England the Pension’s Office sent him to Leysin

in Switzerland to have Heliotherapy under the famous Dr.Rollier.

He attended the Quisisana Clinic where it was discovered that he

had a tuberculous kidney. This was removed at Montreux. As he

improved he acted as assistant Secretary to Dr.Rollier in French,

German and English and also tutored the sons of three American

millionaires. He attended Mass daily, climbed mountains, skied and

also instructed a Russian lady who became a Catholic. His mother

visited him at Leysin but she was unapproachable as regards the Faith.

Before leaving England he had been received into the Third

Order of St Dominic at St Dominic’s Haverstock Hill by.Fr Wulstan

McCuskern, taking the name ‘Francis’. Of this he wrote:

“I can never say how much that meant to me in the next three years,

nor how much support it gave me. It was a most wonderful grace.”

Discharged from Leysin in 1925, he decided to visit Rome

for the Holy Year. Despairing of ever being healthy enough to

become a Dominican in England, he had kept in touch with the

Salesians in Cape Town where he had called on his way to England

Now he decided to visit them in Turin. After a week in

Turin he went by train to Rome feeling ill, and went straight into

a nursing home near St.Peter’s with pneumonia. Here he heard

that St.Thérése of Lisieux was to be canonised on his birthday,

the 17th of May. He was not allowed out of bed until the 15th,

but felt quite well on the 16th. He managed to get a ticket for

St.Peter’s and shared a stool with an Italian lady. After this he

spent four days sight-seeing in Rome. On a later occasion, after

the canonisation of St.Martin de Porres, sitting in the Sistine Chapel

and looking at the ceiling, he remarked that he had seen it before

but had not appreciated it at the time. On his way to Switzerland

he fell ill and “bolted for England." He had typhoid and was sent

to Winchester Hospital and then to an officers’ Convalescent Home

in Brighton.

While at Leysin he very nearly became engaged to a Portuguese girl

but knew that he had promised his life to our Lord. It was here too

that a Dr.Dillon, son of the Irish politician, introduced him to the

works of St John of the Cross and St.Teresa of Avila which he studied

with great joy:

“It is not to be suggested that I was able to understand half of what

I read, but those books contain an attitude towards Almighty God which

was just what was able to destroy the last of the false Mysticism in

which I had been brought up. Here was the real thing, the love of God

and the workings of God, and an asceticism which turned to Him for

love's sake and not a self-centred culture.”

Settled in Brighton, Francis began to make notice boards, ping-pong

tables and cupboards, for the local parish. This ied to him making a

pamphlet rack for Catholic Truth Society pam- phiets and business

became so good he began to develop a small factory. About September

1925 he was introduced to the Catholic Evidence Guild and made his

debut on a street corner in London. He spoke many times at Hyde Park

Corner, the Bull Ring in Birmingham and on the beach at Colwyn Bay.

He eventually became Master of the Guild in Brighton.

In January 1926, the Brighton Guild was without speakers.

Francis who intended to go back to Africa to join the Salesians,

wrote to Don Tozzi in Cape Town and explained the position.

He was told to remain in Brighton. But the carpentry work was

growing and he did not see how he could enter religious life.

Meeting Fr.Peron O.M.I. from South Africa, he was advised to

make a retreat at the Carthusian Monastery near Brighton, Park-

minster. This he did, and asked to join the Carthusians but was

told he must be a Catholic for ten years. He tried again a few

months later, but in vain. A friend advised him to see Fr.Vincent

McNabb, the Dominican. Fr.Vincent heard of the acceptance of

him by the Dominican Order, the TB, the Salesians, the Carthu-

sians and the workshop at Brighton. He asked: “What about

your Dominican vocation. You were never refused were you?”

Francis said it seemed to have fallen through, but was told that

he shouid settle that matter first. He then saw Fr.Bede Jarrett,

the Provincial, and asked to be allowed to go to the Novitiate at

Woodchester.

As a result of this, he handed over his rack-making business —— the

rack in Cape Town Cathedral in the sixties was made by him — and it

was arranged that he should enter on January 2nd 1927, the birthday

of St.Thérése, Of his arrival he wrote:

“I was at home at last, and through the kindness of the

Order have been at home ever since.”

He had already been professed in the Third Order of St

Dominic and had taken a private vow of chastity.

DOMINICAN

1927 - 1931

Fr.Nicholas, writing of the things that helped him most when

he became a Dominican; saw the obedience in which he was

brought up at home, which he had to practise in the Cadet Corps,

tne Police and Flying Corps and in the home of the German headmaster,

as invaluable training for religious life. "One was trained to

follow the mind of a Superior and was satisfied to do so.” As

he was thirty-six when he entered the Dominican Novitiate, he found

it a great help in acclimatising himself to the new way of life.

Spiritually, he found that his reading of the Carmelite classics and

Fr.de Besse’s book ‘The Science of Prayer’, which he studied deeply,

a great help. A remark of Dom.Paschal of Charterhouse remained with him:

“Pray for the Gifts of the Holy Spirit and study them. They

work, as it were, like instincts.”

This remark he followed up all his life and

“it has been the main theme of all the Retreats I have given

and the key point of all my spiritual life.’

So Francis joined the Dominican Novitiate at Woodchester

in Gloucester on the feast of St.Thérése 1927 taking the name

‘Nicholas’ as his religious name. Of the Novitiate he notes:

“the confined space, the length of time behind locked doors, the

new-and-sparse diet, the drying up of topics of conversation, and

the amount of consideration for others with the personal sacrifices

in small things that the life required, was a strain on everyone

— and a very useful training.”

He found himself speaking to himself:

“Weil, this may be God's will, but it never would have been mine.”

Very soon he was put onto carpentry, doing all kinds of jobs,

but it was difficult to get an assistant to ‘hold the other end’

since silence had to be preserved.

His back troubled him and treatment was difficult to get. He

tried to train novices to get out the ‘kink’ but was unsuccessful

and had to put up with a great deal of pain. Life was rather a

battle with pain, diet, confined space and close companionship

with much younger people.

Then his father needed his pension and Nicholas had to appeal

to people to pay for his keep, clothes etc. Like all novices he

found the rubrics for saying Office in Choir a great difficulty.

Lifting a chest of drawers one day, he put the sacro-illiac

joint out and had to spend a week at the Priory in London while

Johnstone May put it right again. Back in Woodchester his back

went wrong again. Faced with the decision between leaving or

not, he decided to carry on and got one of the Novices to pull his

back into place again.

The rest of the Novitiate year passed peacefully and he made

his first Profession on the 29th January 1928 and went to Hawkes-

yard in Staffordshire to begin his studies. January the 29th was

the feast of St.Francis de Sales and his name was Francis and

his link with the Salesians in Cape Town had kept him steadily

inclined towards the religious life while he was in Switzerland.

Hawkesyard, after Woodchester "was like coming out of a

long dark tunnel into the light". Here he found companionship

and was soon back at his carpentry. He was “immensely happy in the

life at Hawkesyard and was learning many things besides my studies.

I was realising concretely that the spiritual life is built up also

by the attendance to duties that obedience brings. This is something

that is little realised in the world, and not always in religious houses.”

He found an osteopath in Birmingham who put his back

right again, had two operations and, after the second, spent three

months on his back. However he managed to pass his examinations.

After panelling the Common Room at Hawkesyard and working

in the chapel sanctuary, he began to cough blood. TB had

recurred and the Pension Authorities sent him to Cranham at the

end of July 1930. This was the end of his formal studies. All

the rest were done privately.

At Hawkesyard his chief friends were Francis Moncrieff, Benet

O'Driscoll and David Donaghue. He was influenced by Fr.Rupert

Hoper-Dixon who taught Logic and by Fr.Hugh Pope. He heard

Fr.Bede Jarrett talk about his intentions in opening the new Priory,

Blackfriars, Oxford, which took place at that time. Fr.Bede said

he had no special intention but a lady had donated three houses,

so he concluded that the Holy Spirit seemed to want this. Such

confidence and courage had a great effect upon Nicholas and it

was with him during his years at Potchefstroom.

Fr.Gervase Matthew, who also had an influence upon him,

started a club for learning Hebrew which Nicholas joined. At

this time he had to break off a friendship with a woman and her

daughter who had helped him materially since he joined the Order.

He accepted this under obedience and in connection with it he

records several possibly mystical graces he received. In Switzer-

land at prayer he heard our Lord within seeming to say: “Do you

not realise that I am a friend and much more. He had later some

rather similar experiences when he got absorbed in prayer. At

Hawkesyard he felt he experienced a very close sense of the pre-

sence of God. ‘

At Cranham Sanatorium Nicholas was coughing blood and

Fr Dunstan Sargent, a Dominican, anointed him:

“It had a tremendous and felt effect on me, even stronger

than that which I experienced at my baptism in Cape Town.

I was overjoyed and felt that now I belonged completely to

Almighty God... This was a matter of experience, as it were,

a rejoicing in fulfilment. It is a joy that has remained with

me....”

At Cranham Nicholas wrote a number of controversial letters

and did a tremendous amount of study, working through a book

of Philosophy and the Summa contra Gentiles of St.Thomas, Garri-

gou-LeGrange’s ‘Dieu’ and a summary of his ‘De Revelatione’.

He read steadily at his Bible too. In spite of his ill-health he had

abundant energy for study. He found there was a good deal of

anti-Catholicism in his environment, but felt the people concerned

good at heart. In the Sanatorium he was examined for his Solemn

Profession and was taken by car to Woodchester for the ceremony

on January 29th 1931.

VI

STELLENBOSCH — SPRINGS — POTCREFSTROOM

1931 - 1948

In August or September 1931 Nicholas left Cranham and

stayed in Brighton where he spoke for the Catholic Evidence Guild

once again. He was also allowed to visit Lourdes with one of

his brethren. He had suggested to Fr.Bede that he might be

useful as a Russian speaker but Fr.Bede had plans for him to

return to Africa. So he sailed for Cape Town on October 6th 1931.

Nicholas was a deacon when he arrived in South Africa again.

He went to the recently acquired property at Stellenbosch where

Fr.Wilfrid Ardagh had been for a year. As the buildings were in

poor shape Nicholas had plenty of scope for carpentry. Mean-

while he studied Theology. However he soon collapsed from

overwork and was in the Military Hospital at Wynberg for about

three months. In hospital he helped instruct an Afrikaans lady

who became a Catholic and also improved his Afrikaans in the

process. He also studied the Summa of St.Thomas in English.

On his return to Stellenbosch he was advised to go and live

in the Highveld and he stayed for six months with the Marist

Brothers at Observatory, Johannesburg. Here he learned to drive

and helped level a football field, besides studying. Having passed

his exarnination for Holy Orders and being assigned to work at

Potchefstroom, he was ordained there by Archbishop Gijiswyk

O.P., the Apostolic Delegate, on October 15th 1932, the feast of

St.Albert. Fr.Peron O.M.!. assisted him. He preached his first

sermon in the Redemptorist Church in Pretoria where there was —

the custom of ‘ringing’ the priest out of the pulpit, so that his

sermon was left in some confusion. While on holiday at Hout

Boy he was able to do some apostolic work among the Coloured

people there, as there was no church at the time.

In February 1933 Nicholas was sent to Springs to take care

of the Payneville Parish there. Before this, however, he gave a

retreat to the Christian Brothers in Fretoria recovering from a bout

of bronchitis to do so. He found now that the stock of notes

he had taken over the years was a good standby in place of the

formal studies which he had missed.

His study of Vedanta philosophy also helped with its concentration

on an ultimate goal.

Nicholas began his mission work at Springs with some disadvantage.

As he wrote:

“I had never attended a lecture in Moral Theology; I had heard

one lecture in Dogmatic Theology ... The only Canon Law

was what I had learnt in an armchair at Stellenbosch .. .

I had never heard of Pastoral Theology. I knew no word of

any African language. I had no money and no transport...”

Gradually, wtih the help of many people including some of

the congregation, the Church was furnished and a schoo! opened.

In April, after three months, he was sent to Potchefstroom Mis-

sion, since Fr.David Donaghue had broken down.

The experience of Mission at Springs had taught Nicholas the

need for Pastoral Theology and he worked through a number of

books on the subject, reading a fixed number of pages a day.

Looking back he saw ‘organising’ as a keynote of his life:

“I know I have never been a gambler. I could put any amount

of work, preparation and sacrifice into something that I

reckoned within my power to achieve, but had no patience

for uncertainties. Perhaps that is why I never cared for

fishing... Certainly I know I have done a number of things

in my life ordinarily called dangerous, but aways beforehand

I had it all worked out.”

He took over the Potchefstroom Mission from Fr.Donaghue.

St.Louis Bertrand Parish was at that time a small schoo! chapel

with a 100 African children taught by two sisters. The sisters

were planning to enlarge it and build a Convent and Priest’s house.

There was an out-station at Muiskraal, 32 miles away, another at

Machavie with a school, 12 miles away, 10 miles of which

was footpaths. Previous missioners had travelled by bicycle,

but Nicholas could not do this and had to have a car.

Nicholas stayed in the presbytery in town and went down

daily to the Mission. The two sisters drove the two miles daily

for twelve years in a ‘Spider’ cart drawn by a white horse. Of

the sisters he remarked:

“what would Mission life be without the sisters. I don’t

really know, not having tried it, but shudder to think.”

The Mission was a two-roomed building with 100 children

of whom nine were Catholics. There were 169 Catholics and

catechumens in the Township and District. The two, and later,

three, sisters at that time were invaluable and Nicholas learned

about Mission work from Sister Anacleta who pointed out to him

the jobs he should be doing. So he began to visit the parish and

discover the things which needed to be done.

Money, as ever, was a problem. For a long time his pension

was paid to his father to whom Nicholas had willed it at his Pro-

fession, but later he was able to use it for his Mission work.

After a time he began teaching in the school and this continued

almost uninterruptedly until 1948. He also partitioned off a

portion of the building as a sanctuary with the Blessed Sacrament

and two small rooms as a sacristy, and a livingroom. So he moved

down to St Louis Bertrands and lived in the roorn until the con-

vent and presbytery were built in 1934. After a time owing to

difficulties of personalities Nicholas took over the school, while

Sister Lioba, who was “old, deaf and nervous but had the heart

of a lion and the fortitude of a saint took charge as Superior.

Nicholas worked towards getting the school recognised by

the Government and a change from the heroic makeshift period

to a more normal one had to be made. School fees and the

increasing number of children provided some funds and new class-

rooms were built on the verandah. There was some opposition

from other church schools and the Education Department decided

to register the school in order to control it. A church worker

from Germany built two more classrooms at this time.

Meanwhile the parish was developing in the surrounding district:

“God was very good to us. I had only to keep running. He

opened up opportunities in every direction.”

For a while Nicholas taught Stds III-VI with 35 children

together, but gradually as new teachers came along he was able

to teach Std VI alone. Then a farm school was started at Vaalkop

with a room for a Church. A catechist-schoolmaster, Alpheus,

took charge and evangelised the countryside. Looking back,

Nicholas wondered where the money came from all those years.

The work spread. There were more Mass centres and farm

schools. The Ventersdorp and Lichtenburg districts were covered

as far as the Botswana border. There were 23 outstations and

about 13 schools and, although other Missions took over some

of these, there were still 19 outstations and 11 schools.

After six years a sister took over the Principal’s position

in the Township school and Nicholas continued teaching there.

During this time he had ilnesses and operations, but also found

time to give Retreats in different parts of the country. He recorded

his Mission experiences in some 300 Mission stories published

in the ‘Southern Cross’ newspaper. In those days a Sunday

started at 5 a.m. and, apart from coffee, ended at 6 p.m. with

the first real meal of the day followed by Benediction at 7 p.m.

Yet Nicholas taught in school on Mondays for many years. When

he left Potchefstroom in 1948 there were 1200 children in the

school of which nearly 50% were Catholics. In all this work

the sisters were his unfailing helpers.

One of the sisters who worked with Nicholas at Potchefstroom

for fifteen years writes:

“He was a very kind-hearted, zealous and hardworking priest.

He was most grateful for the smallest thing you did for him,

which he always rewarded with a grateful ‘God bless you’.

He was very humble and charitable. Everybody respected

and loved him. Catholics and non-Catholics spoke very

highly of him and were his friends. He helped and encouraged

wherever he could. His motto was: ‘It is better to do what

many would call the unnecessary thing, everything is neces-

sary’. Another saying of his was: ‘work for others, you'll

get another time to rest, or you'll see that those things

find their own strength.’ Often he would say: ‘Marry your

circumstances, make the best of it wherever you are or what-

ever you do.’ He never could agree with the saying ‘I am

resigned to God's will’. ‘No’, he said, ‘give with pleasure

and joy to God what he asks from you.”

This sister describes Nicholas at work — his three Masses on

a Sunday with confessions before and interviews or baptism and

marriages afterwards. She remarked on his patience and the

time he found to give to people. He paid great attention to help-

ing the needy and was especially kind to the sick and suffering. Yet

he was the handyman of the Mission. His motto was: ‘never

neglect any small or trivial fault.’ He duplicated hymnbooks,

wrote newspaper articles and learned languages in his spare time.

Another friend of Nicholas who first met hirn at Potchefstroom

writes:

“Father Nick found the necessity of constantly visiting people

in their homes, however poor, and to enter intimately into

their human life and human difficulties ... His outstanding

virtue was kindness and consideration for others by which

everybody was attracted ... He once said ‘I see Christ in

every man, and Mary in every woman. In every sick man

there is Jesus in the person who is suffering, and in every

poor man it is Jesus who is languishing.’ He lived for Jesus,

he spoke with Jesus, his love was God and his neighbour.”

Bioscope (cinema) shows became a feature of the parish

life especially to entertain the people over the weekend. The

films were carefully chosen and the effort was seen as an apostolate

although it seemed financially not worth while. Dances were

also held and eventually a school hall was built in which films

could be shown. Then some cottages for teachers were built

from a legacy from Nicholas’ father. Next a Secondary Domestic

Science school was opened by the sisters wtih splendid results.

The boys’ Secondary School fees were found partly by setting

the boys making coffins during the holidays. It is reported that a

visiting Provincial slept in a bedroom full of coffins! This school

produced a number of vocations to the sisterhood and priesthood.

Nicholas had a great interest in Scouting, having studied

Baden-Powell’s first book ‘Scouting for N.C.O.’s and Men”,

published at the time of the Boer War and from this book "Scout-

ing for Boys” grew. At Machaviestad he was able to provide for

a Scout Masters’ Course in which some white Rover Scouts

learned to appreciate their black brethren. In 1954 he was awarded

the Medal of Merit by the African Boys Scout Association of

South Africa. Nicholas reflected on how little the European knew

at that time of the African except in the master-servant relation-

ship, a relationship by which they judged everything. How little

did they realise the conditions in the Townships. He noted that

what had happened in England had to happen in South Africa:

“It is only since the beginning of this century that the labour-

ing people of England have been able to assert their rights, as

human beings, to a full human life. That assertion has not yet

been made good in South Africa by the equivalent class, but

it ts certainly going to be in the future, and in the end this

will benefit all."

One of his Dominican brothers who knew him well at this period writes:

“Like any very positive and original character, maybe a saint

but not a ‘plaster saint’, Nick could be a source of endless

joy with his restless energy and his ‘gadgets’. I took over

Potchefstroom once for him. When I got into the confes-

sional stands for books and typewriter dropped from the

door and walls. 1 saw the system by which he ran the bio-

scope, controlled the audience, took the cash and said his

breviary all at the same time. I heard that he not only made

coffins for the district in his carpentry school, but assisted at

the other extreme of human existence by bringing pregnant

women to the hospital from all over the large area. Since

he drove at sixty mph over the dirt roads, we used to wonder

what would happen if a bump precipated a birth and con-

cluded that Nick would be quite equal to the occasion.

He was an interesting mixture of calm and drive. He spoke

slowly and thoughtfully, but was always in some sort of

restrained hurry. His work had to be done, and he was

inclined to inspan anyone handy to help. ‘Do. . . like a

good fellow . . .° could become ominous. He was literally

supercharged. To teach Standard VI, not permitting the

students to fail, running a whole district with 19 outstations

and 11 schools at the same time, running a carpentry schooi

and a bioscope, writing continually for the Southern Cross

and translating books into Tswana and Afrikaans as well as

frequently giving retreats, was more like a three-man job

than a one man job. Add frequent illness and having to

hitch his back into place continually and the incident when

he chased a runaway wife 300 miles in a car to bring her

back to her husband, and it all becomes a phenomenon.

He was not logical —- and perhaps one should say ‘thank

God’ — in all his adaptations to life. He wore miner’s jeans

which he could get for six shillings at the beginning of the

war at the mine stores, and homemade coats made by the

sisters, but he drove a mighty Pontiac which he had obtained

cheaply and which some people thought unsuited to the

‘poor missionary’. It certainly paid off to have a heavy car

when he would be driving along and suddenly turn off into

the veld saying: ‘There is someone I have got to see up in

that village’. He thought nothing of ‘popping’ the hundred

miles up to Johannesburg and in a phone discussion with a

sister which had not reached full agreement — that is, probably,

not what Nick wanted — I heard him offer to ‘pop’ the two

hundred miles from Boksburg to Newcastle to discuss it. I think

the sister must have given in, since he did not need to go.

To me he was the perfect British colonial civil servant or com-

missioner turned priest. I expect he enjoyed getting out

his service revolver when he drove the sisters on dangerous

roads at night. But there was no doubt about the ‘turned

priest’. I used to wonder if some of the energy came from

Yoga about which he used to talk with more tolerance than

about theosophy. But as 1 read the foregoing pages, I feel

sure again that it came chiefly from the right source — from

an intense Christian spiritual life and love. Fr.Nick was the

product of a great imperial civil and military tradition, and in

early life tested by the moral confusion and illness existing

in its core. He used the best in it, and triumphed over the

“iHness”, to reach a life totally dedicated to God and man

("always think of the other fellow first"), in a way that never

rested but seemed to be consciously minute by minute.”

In 1948 Nicholas fell off a ladder in the Church and broke his

wrist, being laid up for three months. At this time the Dutch

Dominican Vicariate was to take over that part of the Transvaal

and Nicholas left Potchefstroom for good in August 1948.

VII

SPRINGS — BOKSBURG

1948 - 1958

In August 1948 Nicholas was assigned a temporary post in

Springs. With his left arm still in plaster, he took over the Payne-

ville Mission while Fr.Oliver Clark was on leave. There were

some 19 Compounds for mine labourers, 9 hospitals, large and

small, and 1000 parishioners in the Township with three out-

stations. Nicholas had to learn the method of keeping the accounts

in detail, visit the Compounds to announce forthcoming Mass

and in general get to know the people. He found the sad side

of the work in the fact that one only made contact with the

miners perhaps once or twice during their nine or ten months

contract —- 4000 of the parishoners were temporary ones whom

one saw in sickness or accident or only to bury them. Considering

the circumstance of their life, he found it remarkable how they

kept in touch with the Church.

As usual Nicholas found things to do about the Mission,

widening the altar, making altar rails. He got a promise of more

salaries from the Education Department if more classrooms were

built. He got them built by a European firm since the Bishop did

not think priests expendable on supervising African labour. The

Parish Priest, when he returned, would have preferred supervising

everything himself to save expenses. In the event some help

was given by the Bishop to cover costs, but a considerable debt

remained,

At the end of this task, Nicholas was able to take a six

months holiday. First he went to stay at Cala in Tembuland

where he gave a retreat. In the hospital there, he re-arranged

the system of bells and water tanks.

Of the retreat some sisters remarked: ‘That was a strange

sort of retreat: nothing about Hell or mortal sin!’ Nicholas re-

flected:

"I had, indeed, worked through one of the Gospels, trying to

bring out the Christian life as lived by our Lord, and that

is a quieter method than sermons on selected subjects includ-

ing Heil and mortal sin. Maybe the dears missed a certain

thrill obtained from those two sermons. I wouldn‘t know.”

He also gave four other retreats. At this time he travelled

to Potchefstroom for the ordination of Fr.Samuel Motswenyane,

and then returned to Springs. From there he visited the Kruger

National Park and went on to Pietermaritzburg for another retreat

and then back to Cala with retreats at Fort Beaufort and King

Williams Town. At Cala he had an operation for a cyst on his

foot and another for a hernia. Then another retreat at Rivonia

near Johannesburg and back to Springs. He had travelled 9000

miles, given six ten-day retreats and two weekend ones and

had had two operations.

While ali this seems to enlarge on the quantity of his labours,

it does, nevertheless, indicate an indomitable spirit in a man with

many ilinesses and difficulties to contend with throughout his life.

At the beginning of 1950 Nicholas took over the Stirtonville

Parish in Boksburg from Fr.Synnott. He began teaching Standard

VI which had not existed until then, but after two months went

down with bronchitis. At this time his brother Will came on a

visit. Nicholas was four months in bed and after his brother left,