Holy Man

Sri Ramana Maharshi has India's answer to most of man's problems

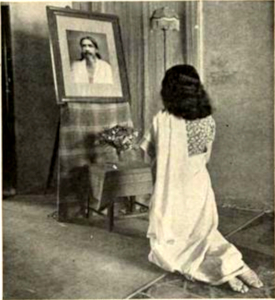

"OH yes," the aged Hindu explained. "The defeat of Adolf Hitler was one of the master's greatest achievements. It was to an extent by thought transference. In fact you might say that Adolf Hitler was an undivine force sent into the world especially to try the master. The master works for the realization of the divine on earth. Of course Hitler was doomed," he added with quiet finality. No breeze stirred the banana trees in the sun-baked courtyard outside. In the adjoining foyer a woman in a sari knelt before a large framed photo of "the master," offering flowers and mumbling prayers: I had no idea whether the master, Sri Aurobindo, one of the most famous yogis in India, would endorse this somewhat sweeping account of the issues involved in World War II. I suspected that his explanation, at any rate, would be more complex. Sri Aurobindo is regarded in India as a formidable thinker as well as a sage. His ashram (which means the establishment built to house his spiritual disciples) includes dozens of impressive modern buildings and covers a large part of the French-administered town of Pondicherry near the southern tip of India. It is no exaggeration to say that Sri Aurobindo's ashram is Pondicherry's leading industry, attracting thousands of pilgrims annually from all over the nation.

I was not to see Sri Aurobindo, I knew that beforehand. He is reported to have a radio and to read all the newspapers, Sri Aurobindo lives in almost complete seclusion. This seclusion is broken only four times a year, when the faithful are permitted to glimpse the master for a few moments. Otherwise Sri Aurobindo is a hermit. His next public appearance was months away. I decided to move on and visit Sri Ramana Maharshi, an equally famous holy man who lives at Tiruvannamalai, about 100 miles inland. Sri Ramana was reported to be more sociable.

There is no place to eat at Tiruvannamalai, so I had the cook at Pondicherry's Grand Hotel de l'Europe fix me some provisions which my bearer, Francis Xavier, loaded into the back seat of the rattletrap car I had hired for the journey. Francis Xavier was an Indian, but he was no Hindu. He was one of India's two million devout Roman Catholics, and he had taken a dim view of the whole expedition. "Why you like all this devil mischief, sir?" he inquired gloomily, shaking his white-topped head (he looked like an Indian Uncle Tom). "When we go back to Madras way, we go to Mass. Very nice, sir, very beauty." Then he pulled himself together with an air of military stoicism. He had formerly been the proud servant of a long line of British officers, most of whom had died impressively from a variety of diseases including pneumonia and plague. He talked interminably and reverently about their deaths, assuring me that he prayed for their souls every day, and had started to pray for mine too, Francis Xavier prayed for all his employers.

We drove in silence until presently he turned to me. "Map, sir?" he inquired with an efficient look. This was the signal for one of our most constant ceremonies. I had gotten into it by an innocent deception when I had once expressed a desire for a map of Bombay, and I had been forced to continue this deception all over South India, The map which he always drew proudly from his pocket was a map of Ireland, I had studied it repeatedly and gravely at crucial junctures everywhere between Bombay and Pondicherry. It had long since become far too lato to disillusion him. I studied the map again with concentration and handed it solemnly back to him. "We will go to Tiruvannamalai," I announced.

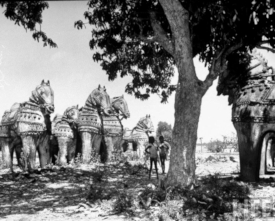

Tiruvannamalai (the word means "sacred, unscalable mountain") is a ramshackle town with a very holy reputation. It was built ago at the base of a conical mountain which is widely regarded in south India as a symbol of the god Siva. It is approached through a dry, boulder-strewn biblical-looking landscape where huge terra-cotta images of gods and horses stare quietly at travelers from nooks by the roadside. The main image at many of these shrines isa fearful-looking mythological figure whose name, Francis Xavier explained, is Bhima. Every time Francis Xavier caught sight of Bhima he crossed himself, "Devil mischief," he muttered defiantly, Even for a devout Indian Catholic, south India is too full of ancestral deities to be an entirely comfortable place, and the sheer exuberance and fantasy with which the Hindu imagination has ornamented the landscape is enough to unhinge even a Westerner's sense of realism.

The power of religion in India is something unimaginable elsewhere in the contemporary world, It operates on hundreds of levels, from folk-deities like Bhima to the most abstruse and elaborate structures of Hindu theology, each level appropriate to a particular social rank or caste. Progressive intellectuals – scientists, industrialists, politicians – in big cities like Bombay and Calcutta rail against it, blaming it for India's material backwardness, but its waves lap at their very doors, It prescribes the begetting, eating, marrying, dying, business and recreation habits of the pious Hindu to a point where every hour of his waking life is a ritual of some sort, and it makes India seem to some Westerners a curious nation composed almost entirely of priests.

Even India's political life, with all its forms borrowed from Western democracy, is a series of religious ceremonies to the Indian man in the street. The vast crowds that assembled to see and hear Mahatma Gandhi and that assemble today to pay homage to his brilliant and progressive successor, Pandit Nehru, are following one of the oldest Hindu rituals, the ritual of darshan, in which throngs have gathered for thousands of years to witness the presence of holy men. India has thousands of holy men who range from naked, ash-strewn roadside ascetics to highly educated Cambridge graduates. It has a corresponding hierarchy of gods ranging from sticks, stones and trees up through idols like Bhima to the abstract conceptions of Hindu metaphyics. At the top of the hierarchy of holy men are the proprietors of this metaphysical world, the great yogis of which the most famous in all India are Sri Aurobindo and Sri Ramana Maharshi of Tiruvannamalai.

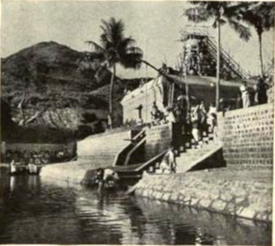

Sri Ramana's ashram lies at the foot of the sacred mountain a little way beyond the town. Unlike the town itself, the ashram is carefully swept. It consists of several dozen simple stone buildings, a number of bare courtyards and a brand-new Hindu temple sprouting gods like candles on a birthday cake, all of them luridly painted and almost indecently shiny. The rest of the ashram is almost as up-to-date, Enameled labels, exactly like American traffic or subway signs, indicate directions, rules of the ashram ("It is forbidden to touch the person of the Maharshi") and various buildings, There is a bookshop where the Maharshi's publications are sold. There is an administrative office presided over by the Maharshi's brother, a dour-looking Brahmin who is responsible for the ashram's business and promotion. There are the Maharshi's own living quarters, his open-air darshan hall complete with a carved stone couch to lie on, and the cottages and dining halls in which his disciples sleep and eat.

The place has 20 or 30 permanent residents, and thousands more in and out on visits, especially on holidays or occasions of pilgrimage. When a yogi gets to be as famous as Sri Ramana Maharshi, his establishment represents a considerable investment in real estate and construction. At the rear of the main courtyard there is an animal cemetery where carved gravestones commemorate Sri Ramana's former pets. They include a bird, a dog, a monkey and a cow named Lakshmi (after the goddess of wealth) who died at the advanced age of 22. The present pet is a white peacock which struts importantly around the courtyard. It is a gift from the wealthy Maharani of Baroda.

Calendars and clocks

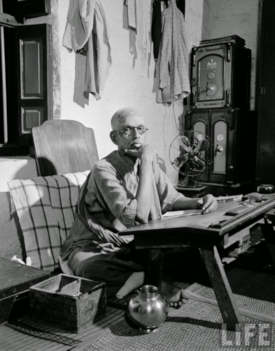

"I am an American journalist," I explained to the priestlike man in a crew cut, robes and sandals, "Are you interested merely in something to write for your paper?" he inquired. "Or have you a deeper purpose" I replied quite shamelessly that I was in search of salvation. He nodded with grave satisfaction and began showing me about the establishment. I inspected the temple; I was shown a miraculous well which had appeared fully dug after the removal of three handfuls of sand. I bought some books in the bookshop. Then I was shown Sri Ramana's quarters, a long, bare room with a flagstone floor, sparsely furnished with several bookcases and another large couch. A number of life insurance calendars and several alarm clocks showed that the Maharshi had a particular interest in the passage of time. There were no chairs. I was then led to the men's dining hall where, seated on the floor, I drank tea with several of the faithful. They included a former professor of English literature from the University of Madura, one of the most famous authors in India, several Europeans and even an American or two.

There were obvious questions I had to ask about the Maharshi. "Did he work miracles, cure the sick, bury himself alive or do the other spectacular things most Americans associate with yogis? Oh dear no. The Maharshi had once passed through such a period and could no doubt do these things if he pleased, But he was way beyond all that. "Was the Maharshi anything like the late Mahatma Gandhi?" Oh no. The Maharshi was on a "different plane altogether" from Gandhi. Gandhi had been a political figure. The Maharshi was above and beyond politics. What did the Maharshi's followers think of their neighbor Sri Aurobindo?" Here there appeared to be a certain sense of rivalry: Sri Aurobindo was a holy man all right. But he had been reported to perform miracles, like curing the sick, with considerable publicity. The Maharshi would never do things as publicly as that. He had done plenty of curing in his time. But when he had any curing to do, he did it in private. "Had the Maharshi and Sri Aurobindo ever met?" No. The Maharshi hadn't left Tiruvannamalai in 50 years, and since Sri Aurobindo never left Pondicherry there was no likelihood of their ever meeting. I gathered that the Maharshi was the center of a self-contained universe which hardly recognized the universe of Sri Aurobindo. To the Maharshi's disciples, the Maharshi piloted the whole world from his ashram. "The world follows him," they assured me, "Even those who don't know they are following, follow him." I was back again at that stage of the argument which held Sri Aurobindo responsible for the defeat of Adolf Hitler, but this time it was Sri Ramana Maharshi who controlled global destiny.

Darshan for the faithful

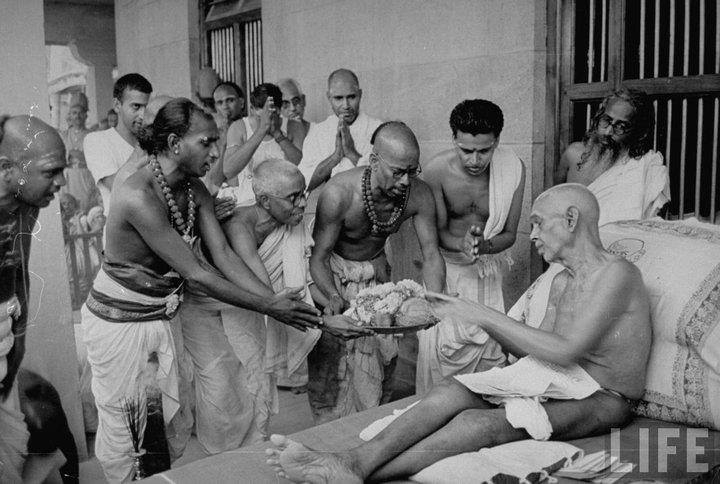

After some conversation and tea drinking I was led into the presence of Sri Ramana himself, He was a small, thin man of about 70 with close-cropped white hair and a stubby beard and mustache, an extremely kindly and intelligent face and a deeply tanned body, clad in a loincloth, He reclined on a massive stone couch propped up with pillows. An American alarm clock ticked on a shelf behind him and a calendar hung from one of the posts that propped a canopy over his couch. An electric floor lamp stood beside his head, a brazier full of hot coals burned in front of him and there was a stand full of burning incense to keep the flies away. He was holding darshan. His couch was flanked by a couple of privileged disciples in the yellow robes of the Hindu priesthood, and sitting cross-legged on the floor about him were two or three dozen people, all gazing rapturously at the master. From time to time a particularly fervent disciple would prostrate himself on the floor before the couch, methodically touching forehead, right ear and left car to the flagstones, Occasionally one of the faithful would come forward with an offering of a banana or an orange, which Sri Ramana accepted with a benign smile, It was forbidden to wear shoes and everyone was barefoot.

Sri Ramana would have looked like a superior human being in any surroundings. He had the quietly assured look of a man who has experienced a great deal and thought everything through to a final, unshakable conclusion. Even an unbeliever could see that he possessed a sort of personal serenity that is rare even in the contemplative Orient. I mumbled a few words of greeting which I hoped were appropriate and was smilingly waved to a place on the floor. The Maharshi spoke very little, sometimes in English, sometimes in the Tamiḷ language which a considerable part of his audience didn't understand. But that didn't seem to matter. "You can attain peace merely by being near him," the professor of English literature explained later.

Arrow shows the seated figure of the youthful Sri Ramana.

The Maharshi was presented with an old book of Tamiḷ scriptures from which he read odd passages aloud, commenting on them in a leisurely tone of voice while his listeners gazed raptly. Finally he stopped talking altogether and simply smiled an endless warm-hearted smile. After an hour or so he rose from his couch and, supporting himself with a long cane, was led by a disciple back to his living quarters, The whole scene had a biblical quality about it, like something that might have happened thousands of years ago. It was a reenactment of the typical scene between master and disciples that has been going on since long before the time of Buddha and that continues in India today as if time stood still and history did not exist.

The fact (to them) that the Maharshi was the center and leader of the world did not particularly conflict in his disciples' minds with the fact that Sri Aurobindo, a hundred miles away, claimed to lead the same world. The devious complexities of Hindu thinking, in which symbols and realities are inextricably confused from the Western point of view, made both hypotheses perfectly tenable, To the yogi the world of appearances – including its wars, dictators, bombs and skyscrapers – is merely an illusory figment produced by the action of the senses. The real world (which is not the world one sees) is to be found only when the avenues of sense perception have been methodically closed off, and the inner soul is brought into harmony with the eternal essence known as Brahman, a Sanskrit term that conveys something analogous to the Christian mystic's idea of God. Yoga, the technique of the yogi, is a method of attaining this state of harmony.

There are numerous kinds of yoga, all of which involve the shutting out of the material world and the concentration of the faculties on the inner self. Some of them require more or less spectacular bodily techniques – control of breathing, special austerities of diet, particular ways of sitting to invite contemplation, and so on – and result in trance-like states and peculiar powers that have often baffled Western psychologists and amazed Western laymen. India is full of exhibitionistic yogis, pseudo-yogis, outright tricksters, fortunetellers and magicians, who claim all sorts of supernatural powers and perform amazing stunts. Indians, who have an unquenchable love of anything fantastic, magical, or supernatural, follow them in droves and most Westerners, quite rightly, regard them as circus freaks.

But great yogis like Sri Ramana regard all this magic and trickery as child's play. Their disciplines are aimed at a purely religious goal. Yoga in its higher aspects is part and parcel of the religion of Hinduism. And Hinduism is not only one the world's oldest and most durable civilized religions, it is also one of the world's largest, counting some 230 million orthodox followers in India alone. Through its vast protestant branch, Buddhism, it has spread throughout the Orient, influencing the thinking and ways of life of nearly 380,330,000 human beings. With the East awakening from its subject status and playing an increasingly independent role in international affairs, these figures indicate something of political as well as philosophical portent.

Hinduism is not only old, durable and extensive; it is unquestionably the most complicated religion in the world, It owes some of this complexity to the mental attitudes of a people who have always loved intellectual elaboration for its own sake. What the West calls theology has expanded in India to the proportions of a universal science which includes nearly every aspect of Indian culture. Indian art, music, literature, psychology, even Indian sociology and economics (except where they have been influenced by the West) are all theological pursuits, This theology, which Westerners often refer to as Hindu philosophy is by no means primitive. Its literature would already have filled vast libraries before the Christian Era, and it has been growing ever since, It includes enormous mythological epics, moral treatises, dramas, technical studies and commentaries. It encompasses a huge amount of what even Western scholars concede to be great literature and a mass of obscure metaphysical speculation that has, in its time, touched on most of the major problems of Western thought, The West often forgets that it was the Hindus who invented the concept of zero in mathematics and who evolved the science of algebra. They also, in their peculiarly vague, dreamy way, anticipated countless Western scientific hypotheses, from the theory of atoms to modern psychiatry's concept of the unconscious mind. Of course they failed to match the progress of Western thought in the field of experimental science.

Experiment vs. Contemplation

But to the orthodox Hindu mind, which considers the material world an illusion of the senses, experiment has never seemed important, While the Westerner busied himself with test tubes in an effort to subdue and comprehend his material environment, the Hindu simply sat and thought. That, as India's progressive politicians know, is one of the main reasons for India's material backwardness today. It is also one of the reasons why Westerners find it difficult to understand India and why they often underestimate the Hindu mind which in morals, mathematics, psychology, philosophy and other fields of more or less subjective thought is at least the equal of our own.

The most obvious feature of Hinduism is the overwhelming array of gods, demigods and mythological figures to whom the average Hindu pays homage. They exist by the thousand in the form of animal-faced, eight-armed and otherwise fantastic statues that adorn the walls and roofs of Hindu temples, To the simple-minded Hindu they are idols to be propitiated and fostered according to the rules of primitive ritual. To the more intelligent and educated Hindu they are symbols of abstract ideas – fertility, wealth, wisdom and so on. They are led by a trinity of superior gods who represent forces of nature: Brahma, the four-faced creator of the universe; Vishnu, the preserver, and Siva, the multiple-limbed god of dissolution. These three are survivals of ancient deities who have existed in various forms since the earliest records of Oriental civilization. Behind this complex facade of polytheism lies a structure of abstract thinking that is more comprehensible to the Western mind. Its outstanding tenet is the doctrine called "reincarnation" – the idea that the human soul never dies but is reborn again and again like the vital force that causes plants to sprout, seed, die and resprout. Ultimately, by a process of purification, the soul becomes free of the necessity of repeated rebirths and is permanently united with the vital force itself. This final state is the goal of all human life, and the surest method of attaining it is the discipline of the yogi.

The ramifications of this doctrine form the subject of what is perhaps the greatest work of literature ever produced in the Orient, the Bhagavad-Gita or Song of God, The Gita, which is to Hinduism what the Sermon on the Mount is to Christianity, dates in word of mouth form from long before the time of Buddha (500 B.C.) and was written down in Sanskrit during the early centuries of the Christian Era. It has been repeatedly translated into English, most recently and lucidly by the British novelist Christopher Isherwood.

It is an amazingly compact document of perhaps 20,000 words and, like many great religious books, takes the form of a narrative. This narrative begins at a moment of emotional crisis when its hero, a young warrior named Arjuna, is about to plunge into battle. Suddenly Arjuna is overcome with an enormous sense of futility. He asks why he should lift up his sword and go about butchering the enemy which, after all, consists of men very much like himself. He is answered by his charioteer, Krishna, a semi-divine mythological figure who has been sent into the world to guide him. Krishna's explanation, involving the nature of life and death, the relation of the individual human soul to the rest of the universe, the true distinctions between good and evil and the Hindu path of righteousness through yoga forms the rest of the narrative.

Seldom in the history of religious and philosophical writing has so much profundity been encompassed in a few pages, and the result is a compendium of the essentials of Hindu relgion. As Krishna describes it, life is an impermanent dreamlike state in which the soul is beset by illusions and desires. The path of the wise man lies in detecting these illusions for what they are and in renouncing all worldly desire, Once independent of his desires and unattached to glory, ambition, pride or any other fruit of worldly achievement, He can go through life in complete serenity and pass from it into an eternal union with Brahman, the omnipresent spirit of all created things. Those who fail to achieve this detachment and serenity are condemned to be reborn into a succession of future lives over and over again until they have learned their lesson.

Now what has all this ancient doctrine got to do with Sri Ramana Maharshi, the sun-tanned old gentleman who lives at the foot of the mountain near Tiruvannamalai? Everything. Sri Ramana's views are extremely orthodox and correspond exactly with those propounded in the Gita, His life of austerity, his renunciation of all worldly desires, his contemplative serenity, his unshakable peace of mind are all part of the traditional equipment of the Hindu. To millions of Hindus he is a living saint and an example. Sri Ramana, they believe, is about to break his cycle of rebirths, When he dies he will be absorbed into eternal union with Brahman. In fact Sri Ramana's soul is already united with Brahman, Only the presence of his physical body, an outer husk connected with the world of appearances, still sustains the illusion that he is a man like other men.

The Education of a Yogi

How did Sri Ramana attain this remarkable state? This question is answered with great enthusiasm by almost any of the devout followers who live at his ashram. Many Hindu yogis reach that state only after years of austere disciplines. Not so Sri Ramana. Sri Ramana was able to dispense with nearly all the elabotate techniques of contemplation. He was practically born a yogi.

Sri Ramana was the son of a reasonably prosperous lawyer who lived near the city of Madura in South India. He was 12 years old when his father died, and his mother and uncles undertook the problem of giving him a good, conventional education. He was a boy of more than average intelligence. But Sri Ramana seemed to have no interest whatever in getting on in the world. He pursued his studies in a desultory way, He had a habit of falling into deep sleep from which nobody could awaken him, He was obsessed by a peculiar dream of a holy mountain which he had never seen or heard of but which ultimately turned out to be the conical mountain of Tiruvannamalai where he settled later in life, At 16, when he was about to enter the University of Madras, Sri Ramana passed through a curious emotional experience which in the West would be considered somewhat morbid. He began seriously thinking about the idea of death. "Who or what is it that dies?" he asked himself, "It is this visible body that dies. But when this body dies, shall I also die? That depends on what I really am. If I be this body then when it dies, I also would die; but if I be not this [body], then I would survive." These reflections on the immortality of the soul, or the true "self as Hindu theologians call it, led Sri Ramana to undertake an experiment. Lying rigid on the floor, he tried to reproduce in his own body a state resembling death, closing off all the sensations, feelings and thoughts that attend the experience of living. When he arose from this state he had apparently discovered by a process of elimination, which reminds one of the Hindu invention of algebra, the unknown quantity he was seeking. He knew the nature of the immortal, indestructible X which remained after all the physical and mental phenomena of life had been eliminated. The equation X = the real Sri Ramana came as a revelation, and Sri Ramana was instantly transformed into a sage.

To the Hindu mind, nurtured on millenniums of metaphysics, this revelation contained nothing fantastic or incredible. It was simply the standard discovery made repeatedly and through various methods by generations of yogis since the dawn of Hindu thought. The remainder of Sri Ramana's long life is described by his followers as a mere chain of outward events which had no further effect on his nature. He grew even more oblivious to his studies and when the family rebuked him for laziness, he ran away from home with three rupees (about one dollar) in his pocket. He made his way, as a mendicant, to the town of Tiruvannamalai where he recognized the holy mountain as his predestined home. He shaved his head, threw all his clothes except a loincloth into the bathing pool of Tiruvannamalai's ancient Hindu temple and sat for days in meditation. At first he meditated in odd corners of the temple. Later he took to meditating in various caves on the sides of the mountain itself. At the age of 21, in 1900, he wrote a small book entitled "Who am I?" which contained the gist of his discovery. He subsisted on chance offerings of food from passers-by, though he was reported to be able to do without food entirely for long periods, Gradually his reputation spread, and pious Hindus from all over India came to sit in his presence and listen to his teaching.

The teaching has since been elaborated by various disciples and now fills numerous volumes and pamphlets, Several Europeans have written books about it. But it contains nothing sensational and little that is new. Sri Ramana is not the founder of a new religion, He seeks no converts, Hinduism has never been a proselytizing religion, and it lacks entirely the organization of the Western churches. Sri Ramana has simply "found his soul," as Westerners put it and is willing, by example and precept, to help others find theirs. The method is merely a variation on a theme that is at leest 3,000 years old. Sri Ramana's favorite point of departure, the question "Who am I?," was stated long ago by Socrates as "Know thyself" and has been echoed by thousands of great moral teachers everywhere. "If only the mind is kept under control," says Sri Ramana, "what matters it where one may happen to be? The mind of the ignorant one, entering into the phenomenal world, suffers pain and anguish. When the world recedes from one's view, that is when, free from thought, the mind enjoys the bliss of the self. There is no such thing as the physical world apart from and independent of thought. Just as the spider draws out the thread of the cobweb from within itself and withdraws it again into itself, even so out of itself the mind projects the world and absorbs it again into itself. The self alone is the world."

There is, of course, no point in logical dispute about religions, A man believes or he does not believe and that is all there is to it, A Christian, who has a more dynamic view of human destiny, might find the extreme subjectiveness of Sri Ramana's philosophy a practical weakness. The average Hindu, whose closest relationships are between himself and the infinite, has failed to evolve the sense of social responsibility that grows from the Judaeo-Christian dictum, "Love thy neighbor as thyself" The average worldly Western man might point out that Sri Ramana's way of life is all right for sages but offers very little help to the fellow who is trying to pay the rent and keep his children clothed and fed. These are some of the differences that have always divided East and West. And India's progressive and industrial leaders are very anxious today to teach India the secrets of the West's material advance and to wipe out the poverty, disease and social inequality of her "phenomenal world" by other methods than pure contemplation. Probably they are right and even Sri Ramana would not deny the temporary validity of their aims. But the yogi takes a longer view. According to his philosophy, the world has seen countless cycles of creation and dissolution. Man's material conquests rise and subside. The world is not really going anywhere in particular. The only thing that is certain is the indestructibility of the human soul, which strives eternally toward ultimate union with the all-pervading essence known as Brahman. Had Sri Ramana, like Sri Aurobindo, defeated Adolf Hitler? Not in the physical sense certainly, But in the yogi's contemplative universe, the "physical sense" is a more or less irrelevant illusion. Sri Ramana's universe is ruled by a power that has long guaranteed the futility of all earthly ambition. According to Hindu theology, Sri Ramana himself is identified with this power. Accepting these premises, anybody can work out the equation. It may not be what the Western mind calls "realistic." But it is certainly not illogical.

Footnote:

This article was summarized in the The Maharshi in America, Jan/Feb 1993 issue of 'The Maharshi'