As I Saw Him, No.10

To the poet the Maharshi was an inspired poet; to the scholar, an endless ocean of knowledge; to the Yogi, a supreme adept established in Divine Union. Everyone who approached him with humility and faith, saw something of themselves reflected back, with greater insight and clarity. It is no wonder that those uneducated but spiritually mature women who served him by cooking in the kitchen saw him as a flawless cook who taught the highest wisdom in simple kitchen chores.

Sampurnamma diligently served Bhagavan in the kitchen for many years and still lives in Sri Ramanasramam today. She can be seen in the Ashrama with cane in hand, walking slowly with short steps, bent, and wearing a well-used white sari which is draped over the top of her head. When you speak to her, a beautiful smile lights up her face.

In reminiscences taken from Ramana Smrti, Ch.10 and a 1989 video-taped interview, Sampurnamma tells us her story.

Bhagavan was born in the village next to ours and my people knew him from his earliest childhood. When he became a great saint with an Ashrama at Tiruvannamalai, my relatives used to go there often, for they were quite devoted to him. I was busy with my household and was not interested in going with them.

When my husband died, I was in despair and thought life not worth living. My people were urging me to go to Ramanasramam to get some spiritual guidance from Bhagavan, but I was not in the mood to go anywhere.

In 1932 my sister and her husband, Narayanan, were going to see Bhagavan and I agreed to go with them. We found Bhagavan in a palm leaf hut built over his mother's samadhi (place of burial). Some devotees and visitors were with him and all were having their morning coffee. Dandapani Swami introduced me to Bhagavan, saying: "This is Dr. Narayanan's wife's sister." As soon as I was introduced, Bhagavan gave a happy smile and said, "Varatoom, varatoom. (She is welcome, she is welcome.)"

When I was able to sit for long hours in Bhagavan's presence my mind would just stop thinking and I would not notice the time passing. I was not taught to meditate and surely did not know how to stop the mind from thinking. It would happen quite by itself, by his grace. I would sit, immersed in a strange state in which the mind would not have a single thought and yet which would be completely clear. Those were days of deep and calm happiness. My devotion to Bhagavan took firm roots and never left me.

I stayed for twenty days. When I was leaving, Bhagavan got a copy of Who am I? and gave it to me with his own hands.

When I returned to my village I was restless. I had all kinds of dreams. I would dream that a pious lady would come to take me to the Ashrama, or that Bhagavan was enquiring after me and calling me. I longed to go again to Ramanasramam. My uncle was leaving for Arunachala and I eagerly accepted his offer to take me with him. On my arrival I was asked to help in the kitchen because the lady in charge of cooking had to leave for her home. I gladly agreed, for it gave me a chance to stay at the Ashrama and to be near Bhagavan.

In the beginning I was not good at cooking. The way they cooked in the Ashrama was different from ours. But Bhagavan was always by my side and gave me detailed instructions. His firm principle was that health depended on food and could be set right and kept well by a proper diet. He also believed that fine grinding and careful cooking would make any food easily digestible. So we used to spend hours on grinding and stewing. He would sit in the middle of the kitchen, watching and offering suggestions.

He paid very close attention to proper cooking. I would give him food to taste while it was cooking, to be sure that the seasoning was just right. He was always willing to leave the Old Hall to give advice in the kitchen. Amidst pots and pans he was relaxed and free. He would teach us numberless ways of cooking grains, pulses and vegetables, the staples of our South Indian diet. He would tell us stories from his childhood, or about his mother, her ways and how she cooked. He would tell me: "Your cooking reminds me of Mother's cooking. No wonder, our villages were so near." I think Bhagavan must have learned cooking from his mother, for if I made some dish very well, while testing it he would exclaim, "Ha, you have made this dish just like mother used to make it." And whenever my going home was mentioned he would say: "Oh, our best lady cook wants to go away."

In the kitchen he was the Master Cook, aiming at perfection in taste and appearance. One would think that he liked good food and enjoyed a hearty meal. Not at all. At dinner time he would mix up the little food he would allow to be put on his leaf - the sweet, the sour and the savory, everything together - and gulp it down carelessly as if he had no taste in his mouth. When we would tell him that it was not right to mix such nicely made up dishes, he would say: "Enough of multiplicity. Let us have some unity."

When I think of it now, I can see clearly that he used the work in the kitchen as a background for spiritual training. He taught us to listen to every word of his and to carry it out faithfully. He taught us that work is love for others, that we never can work for ourselves. By his very presence he taught us that we are always in the presence of God and that all work is His. He used cooking to teach us religion and philosophy.

He would allow nothing to go to waste. Even a grain of rice or a mustard seed lying on the ground would be picked up, dusted carefully, taken to the kitchen and put in its proper tin. I asked him why he gave himself so much trouble for a grain of rice. He said: "Yes, this is my way. Everything is in my care and I let nothing go to waste. In these matters I am quite strict. Were I married, no woman could get on with me. She would run away." On some other day he said: "This is the property of my Father Arunachala. I have to preserve it and pass it on to His children." He would use for food things we would not even dream of as edible; wild plants, bitter roots and pungent leaves were turned under his guidance into delicious dishes.

Once a feast was being prepared for his birthday. Devotees sent food in large quantities: some sent rice, some sugar, some fruits. Someone sent a huge load of brinjals and we ate brinjals day after day. The stalks alone made a big heap which was lying in a corner. Bhagavan asked us to cook them as a curry! I was stunned, for even cattle would refuse to eat such useless stalks. Bhagavan insisted that the stalks were edible, and we put them in a pot to boil along with dry peas. After six hours of boiling they were as hard as ever. We were at a loss what to do, yet we did not dare to disturb Bhagavan. But he always knew when he was needed in the kitchen and he would leave the Hall even in the middle of a discussion. A casual visitor would think that his mind was all on cooking. In reality his grace was on the cooks. As usual he did not fail us, but appeared in the kitchen. "How is the curry getting on?" he asked. "Is it a curry we are cooking ? We are boiling steel nails!" I exclaimed, laughing. He stirred the stalks with the ladle and went away without saying anything. Soon after, we found them quite tender. The dish was simply delicious and everybody was asking for a second helping. Bhagavan challenged the diners to guess what vegetable they were eating. Everybody praised the curry and the cook, except Bhagavan. He swallowed the little he was served in one mouthful like a medicine and refused a second helping. I was very disappointed, for I had taken so much trouble to cook his stalks and he would not even taste them properly.

The next day he was telling somebody: "Sampurnamma was distressed that I did not eat her wonderful curry. Can she not see that everyone who eats is myself? And what does it matter who eats the food? It is the cooking that matters, not the cook or the eater. A thing done well, with love and devotion, is its own reward. What happens to it later matters little, for it is out of our hands."

It was clear that Bhagavan did not want me to treat him differently from others and would set me right by refusing to touch the very thing I was so proud of and eager to serve.

In the evening, before I would leave the Ashrama for the town to sleep, he would ask me what there was to be cooked the next day. Then, arriving at daybreak the next morning, I would find everything ready - vegetables peeled and cut, lentils soaked, spices ground, coconut scraped. As soon as he saw me in the kitchen, he would give detailed instructions about what should be cooked and how. He would then sit in the Hall a while and then return to the kitchen to see how things were moving, taste them now and then, and go back to the Hall, to come again an hour or two later. It was so strange to see him so eager to cook and so unwilling to eat.

In my coming and going I sometimes had to walk in the dark along a jungle path skirting the hill and I would feel afraid. Bhagavan noticed it once and said: "Why are you afraid, am I not with you?" Bhagavan's brother, Chinnaswami, the manager of the Ashrama, asked me, when I came at dusk:

"How could you come all alone? Were you not afraid?" Bhagavan rebuked him:

"Why are you surprised? Was she alone? Was I not with her all the time?"

Once Subbalakshmiamma and myself decided to walk around the hill. We started very early, long before daybreak. We were quite afraid of the jungle - there were snakes and panthers and evil-doers too. We soon saw a strange blue light in front of us. It was uncanny and we thought it was a ghost, but it led us along the path and soon we felt safe with it. It left us with daylight.

Another time we two were walking around the hill early in the morning and chattering about our homes and relatives. We noticed a man following us at a distance. We had to pass through a stretch of lonely forest, so we stopped to let him pass and go ahead. He too stopped. When we walked, he also walked. We got quite alarmed, and started praying: "Oh, Lord! Oh, Arunachala! Only you can help us, only you can save us!" The man said suddenly: "Yes, Arunachala is our only refuge. Keep your mind on Him constantly. It is His light that fills all space. Always have Him in your mind." We wondered who he was. Was he sent by Bhagavan to remind us that it is not proper to talk of worldly matters when going around the hill? Or was it Arunachala Himself in human disguise? We looked back, but there was nobody on the path! In so many ways Bhagavan made us feel that he was always with us, until the conviction grew and became a part of our nature.

Those were the days when we lived on the threshold of a new world - a world of ecstasy and joy. We were not conscious of what we were eating, of what we were doing. Time just rolled on noiselessly, unfelt and unperceived. The heaviest task seemed a trifle. We knew no fatigue. At home the least bit of work seemed tiresome and made us grumble, while here we worked all day and were always ready for more. Once Bhagavan came to the kitchen and saw the cooking done and everything cleared. He wondered that the day's work was over so soon. "No mere human hands were working here, Bhagavan. Good spirits helped us all the time," I said. He laughed: "The greatest spirit, Arunachala, is here, towering over you. It is He who works, not you."

Once a little deer found her way to Bhagavan and would not leave him. She would go with him up the hill and gambol around him and he would play with her for hours. About a year later she ran away into the jungle and some people must have pelted her with stones, for she was found severely wounded with her legs broken. She was brought to the Ashrama. Bhagavan kept her near him, dressed her wounds and a doctor set her broken bones. One midnight the deer crept onto Bhagavan's lap, snuggled up to him and died.

The next day Bhagavan told me that the deer had died. I said: "Some great soul came to you as a deer to gain liberation from your hands." Bhagavan said: "Yes, it must be so. When I was on the hill, a crow used to keep me company. He was a rishi in a crow's body. He would not eat from anybody's hand but mine. He also died."

Once a garuda, a white-breasted eagle, which is considered holy in India, flew into the Hall and sat on the top of a cupboard near Bhagavan. After a while it flew around him and disappeared. "He is a siddha (a saint endowed with supernatural powers) who came to pay me a visit," said Bhagavan most seriously.

A dog used to sleep next to Bhagavan, and there were two sparrows living at his side in the Hall. Even when people tried to drive them away they would come back. Once he noticed that the dog had been chased away. He remarked: "Just because you are in the body of a human you think you are a human being, and because he is in the body of a dog you think him a dog. Why don't you think of him as a Mahatma, and treat him as a great person. Why do you treat him like a dog?" The respect he showed to animals and birds was most striking. He really treated them as equals. They were served food first like some respected visitors, and if they happened to die in the Ashrama, they would be given a decent burial and a memorial stone. The tombs of the deer, the crow and the cow Lakshmi can still be seen in the Ashrama near the back gate.

Who knows in how many different forms animal, human, and divine beings visited this embodiment of the Almighty! We, common and ignorant women knew only the bliss of his presence and could not tear ourselves away from the Beloved of all. So glorious he was.

It has been sixty years, I think, since I came. The days I spent with Bhagavan are memorable days indeed. Somehow, in my old age, I am pulling on with Bhagavan in my heart and his name on my tongue.

Obituary

We are very sad to announce the passing of Sri R. Gouthama of Glendale Heights, Illinois, an earnest devotee of Bhagavan. His father, Sri K. Ramaswami, has been well known to the circle of devotees for over fifty years and founded Ramana Maharshi Trust in Bangalore.

Sri R. Gouthama came to America in 1969 to complete his Masters Degree in Electrical Engineering. In 1972 he settled in the Chicago area until his untimely passing on June 19th, 1992 at the age of 51. He regularly went to Sri Ramanasramam since his first visit in 1965, and one can see Sri Bhagavan's grace in his devout life.

His house was a meeting place for devotees where regular sat-sangs were conducted throughout the year. He had the good fortune of being host to many visiting pilgrims from home and abroad.

Prior to and even during his illness, Gouthama took keen interest in the restoration and editing of all the old films from Sri Ramanasramam and the production of the documentary on the life and teachings of the Maharshi. Just days before his passing, after viewing the completed version of the documentary, he called us to express his joy and satisfaction.

Gouthama's courage and devotion in the face of the developing illness has been an inspiration and consolation to all who knew him. In the hospital, on his final day, as friends and devotees gathered at his bedside, he quietly slipped away amidst the chanting of God's holy name.

Films from Sri Ramanasramam

Part 8

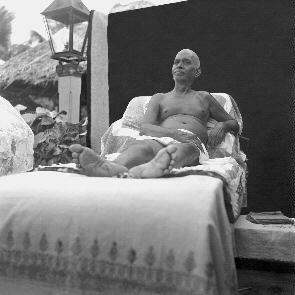

IN 1948, Aravind Bose, a Bengali devotee of long-standing, shot a series of 16mm color films which were collected together and have been commonly known as the 'Bose film'. This film came into the possession of Sri Ramanasramam only in the 1980s. The camera work done in these films displays a considerable amount of professionalism that is absent in most of the other films taken by devotees. But their real value lies in their content.

The film begins with a series of shots taken from up on the hill. We see the terrain surrounding Sri Ramanasramam as it was a half a century ago. And then from Skandashrama we look down on the great Arunachala Temple with a small community surrounding it. Those familiar with Tiruvannamalai will easily observe the sharp contrast to the bustling town of today.

Swami Viswanathan is then seen standing on the overlook at Skandashrama and pointing to places of interest. Mr. Bose's daughter, Maya, stands next to him and looks on. Apparently, Swami Viswanathan served as a guide that day, for we see him again in shots at various other places.

What follows is a series of scenes that are mostly connected with the Maharshi's early life. From Skandashrama we go to Pachaiamman Koil[1]. We then see various sites inside the Arunachala Temple, and scenes from Pavalakkunru and Virupaksha Cave. We also see, on two occasions, shots taken during the Karthigai Deepam festival. There are a great number of pilgrims walking on pradakshina near the Pali Tirtham, the large tank next to the Ashrama. The tank is full to the brim and many pilgrims are bathing and washing their clothes. We see a man being carried in a palanquin by four bearers and a bhajan party with drum and cymbals following. In another scene the images from the Arunachala and the Adiannamalai Temples are seen being carried on procession near the front gate of Sri Ramanasramam. There is one view of the wooded Palakothu where a bearded swami in a loin cloth (Annamalai Swami) walks out of the Ganesha Temple. A short close up shot of the famed white peacock and we come to the Maharshi.

Bhagavan steps out from the southern door of the dining hall, and begins cleaning his teeth while standing on the steps. The attendant Sivananda stands beside him.

Having a short crop of white hair on his face and head, a white towel over his left shoulder, and leaning lightly on his cane, he quickly makes his way east between the dining hall and bathroom. A crowd of devotees follow him.

We soon see him walking again, flanked on both sides by devotees. Then Mr. Bose appears near the goshala (cow shed) and seems to be guiding Bhagavan to the Veda Patasala. The Maharshi stops and about ten priests and students come out and prostrate before him. One gets the impression that this was not a spontaneous occurrence, but rather an orchestrated act. After they all rise, Bhagavan resumes walking with all the priests and students reverently by his side.

Now we come to the part where Mr. Bose's camera is most effective in capturing the unique qualities of the Maharshi in a very natural manner.

We have all read of Sri Bhagavan's love for animals and how he would occasionally go to the goshala to visit those blessed cows whom he looked upon as ashramites, equal to any humans. This next scene takes us there with him on one of his regular visits and we witness, as others did, his love and attention for these often mistreated animals.

Looking somewhat lean and cheerful he walks up to a black cow and begins to gently scratch her back. While doing so he gazes around, looking to see that everything is being done properly. He moves over to a young calf and rubs its back, gives instructions to a worker, turns to the left, takes one step and then a gracious smile adorns his face. The reason is soon apparent. His beloved cow Lakshmi walks straight to him and bends her head down low. He reaches out to her.

At this point, if you slow down the film speed and look at the Maharshi's smiling lips, you can distinctly see him say endearingly "Amma (Mother)," as he begins to talk to her.

Three Verses on Liberation

Those who are students of the Maharshi's written works are aware that Upadesa-Sara, Arunachala-Pancaratna, and the following selection, Muktaka-Traya, are the only verses Sri Bhagavan composed in Sanskrit. Each of his compositions, written for whatever reason, exudes a crisp fragrance of truth and experience, guiding seekers to the final state of perfection.

The verses comprising Muktaka-Traya (Three Verses on Liberation) were composed on different occasions and later collected together. The first of these, Ekam Aksaram, was written when a devotee, Somasundaraswami, went to Bhagavan with a new notebook and requested him to write one letter (aksara ) in it. Bhagavan replied with the punning Tamiḷ verse, which he later translated into the Sanskrit. The second verse, Hrdaya Kuhara Madhye, was written at the request of a devotee and appears in chapter two of Sri Ramana Gita. The third verse, written in 1927, later was translated into Tamiḷ and included as verse number 10 of Ulladu Narpadu Anubandha (Appendix to Forty Verses on Reality).

एकमक्षरं हृदि निरन्तरम्। भासते स्वयम् लिख्यते कथम्॥

ēkamakṣaram hr̥di nirantaram |

bhāsatē svayam likhyatē katham ||

- ekam

- : one,

- akṣaram

- : imperishable/letter,

- hṛdi

- : in the Heart,

- nir-antaram

- : continually,

- bhasate

- : it shines,

- svayam

- : itself,

- likyate

- : is to be written,

- Aatham

- : how?!

1. The one imperishable (letter) itself shines continually in the Heart. How is it to be written?

हृदयकुहर मध्ये केवलं ब्रह्ममात्रम्। ह्यमहमिति साक्षद् आत्मरुपेण भाति॥ हृदि विश मनसास्वं चिन्वता मज्जता वा। पवन चलन रोधाद् आत्मनिष्ठो भव त्वम्॥

hṛdayakuhara madhye kevalaṃ brahmamātram।

hyamahamiti sākṣad ātmarupeṇa bhāti॥

hṛdi viśa manasāsvaṃ cinvatā majjatā vā।

pavana calana rodhād ātmaniṣṭho bhava tvam॥

- hr̥dayā

- : the heart,

- kuhara

- : cave,

- -madhye

- : in the center,

- kevalaṃ

- : alone,

- brahma-matraṃ

- : Brahman only,

- hi aham-aham-iti

- : 'I-I',

- sāksādcw

- : with immediacy,

- atma-rupeṇa

- : with the form of the Self,

- bhati

- : shines,

- hr̥di

- : into the Heart,

- viśa

- : enter,

- manasa

- : by means of the mind,

- svaṃ

- : itself,

- cinvatā

- : investigating,

- majjata

- : diving,

- va

- : or,

- pavana

- : breath,

- calana

- : movement,

- rodhād

- : by control of,

- atma-nistho

- : abiding in the Self,

- bhava

- : be,

- tvam

- : you

2. In the center of the heart-cave Brahman alone shines in the form of the Self with immediacy as 'I-I'. Enter into the heart by diving deep, with the mind investigating itself, or with control of the movement of the breath and abide in the Self.

देहं मृन्मय वज्जडात्मकम् अहं बुद्धिर्न तस्यास्त्यतो नाहं तत्तदभाव सुप्ति समये सिद्धात्म सद्भावतः। कोहं भाव युतः कुतो वरधिया दृश्त्वात्म निष्ठात्मनां सोहं स्पूर्ति तयाऽरुणाचल शिवः पूर्णो विभाति स्वयम्॥

dehaṃ mṛnmaya vajjaḍātmakam ahaṃ buddhirna tasyāstyato

nāhaṃ tattadabhāva supti samaye siddhātma sadbhāvataḥ।

kohaṃ bhāva yutaḥ kuto varadhiyā dṛśtvātma niṣṭhātmanāṃ

sohaṃ spūrti tayā'ruṇācala śivaḥ pūrṇo vibhāti svayam॥

- dēham

- : the body,

- mṟn

- : clay,

- maya

- : made of,

- vat

- : like,

- jaḍa

- : insentient,

- ātmakam

- : ,

- aham buddhiḥ

- : ,

- na

- : not,

- tasya

- : ,

- asti

- : is,

- ataḥ

- : not I that,

- na

- : not,

- āham

- : I,

- ,tattadabhāva

- : non-existence of that(the body),

- supti samayē

- : at the time of sleep,

- siddhātma sadbhāvataḥ

- : on account of the existence of the Self admitted,

- kaḥ aham

- : who am i?,

- bhāva yutaḥ

- : bound to the enquiry,

- kutaḥ

- : from,

- varadhiyā

- : with sharp intellect,

- dṛśtva

- : having seen,

- atma niṣṭhātmanāṃ

- : those established in th Self,

- saḥ aham

- : 'I am THAT',

- spūrti taya

- : with the manifestation,

- aruṇācala śivaḥ

- : Arunachala Shiva,

- pūrṇaḥ

- : full,

- vibhāti

- : shines,

- svayam

- : itself

3. The body, like things made of clay, is insentient in nature and has no 'I'-concept. Also the existence of the Self is admitted at the time of sleep when there is non-existence of the body. Therefore, I am not the body. To those established as the Self and having seen with a sharp intellect adhering to the enquiry 'Who am I?' and 'From whence?', Arunachala-Shiva itself shines full as the manifestation of 'I am that'.