Grace From a Distance

When did I first hear of Bhagavan? It is difficult to imagine a time when one had not. Yet I think it was from Brunton's book Message from Arunachala (first read in the late 40's), and many good talks with a friend of Brunton's. Then in 1950 there was the article in an American magazine describing Bhagavan's last days.

These sources gave no more than an elusive awareness of something I wanted avidly to learn more about. A pilgrimage to Arunachala became – and remains – an unfaltering and deep desire. Imagine my feelings around ten years later when my beloved sister De Lancey Kapleau was able to do just that! And was good enough to write fully about it and send me Osborne's book on Bhagavan's life!

I read through her description of her stay at the Ashram with mounting excitement; read and reread it. Then devoured the book. The last chapters were read late at night when the children and my husband were all asleep, and my heart nearly burst for joy, while grateful tears sprang from my eyes. When I closed the book I sat still for some time, then quite spontaneously prostrated myself in gratitude. Later, in bed, thinking of my sister's letter, I felt an earthy pang of envy that she, not I, had reached the Ashram. You know the sort of thing: "Oh how wonderful – just imagine – I wish it had been I." The jealousy surprised me, a little, but when I recognized and acknowledged it I had to laugh at the jealous one, and said to myself: "But you fool, if your sister went there of course this was part of her karmic pattern. For you, and for anybody, if Arunachala exists anywhere it must exist most truly in the hearts of those who are open to it. So the significance is always within oneself."

At this the field of my vision was lit by a great glow of golden light, and my heart expanded in almost unbelievable joy. The joy deepened and glowed into an incredible depth of peace, which wells up again as I write this.

A few weeks afterwards I was thinking still of Osborne's book, and particularly recalling the beautiful experience of the disciple who felt the pressure of Bhagavan's hand on his heart, in blessing, while far from the Ashram and Bhagavan. Again a swift little pang of envy, and again a self-scolding: he to whom it happened had made himself ready for the reception of such Grace, and it could happen only to the heart which was ripe for it.

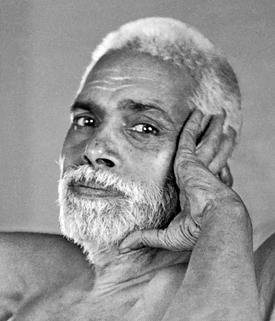

The darkness of the night around me became utterly black, and in my mind's eye I caught a fleeting glimpse of Maharshi's wonderful face. At the same moment I felt a sharp pressure in the chest, just to the right of the breastbone. Everything merged into unutterable peace. I was able to dwell in that peace for several days, during which time errors, disharmonies, misunderstandings, impatience and fatigue became impossible, and my family, who knew nothing of what had happened, responded radiantly in an unbroken harmonious and loving glow. The peace gradually receded, of course, but from that time conscious effort is opening my heart to Bhagavan and I could almost always restore it.

Around this time my mother was taken to a hospital, where she lived for her last three remaining years. Having small children, no household help, and the vagaries of public transportation made it difficult for me to visit her regularly. I have always been deeply fond of this loving mother, and grateful to her for her warmth and enthusiasm. As her body weakened she was much in my thoughts. I was concerned that for years she had feared death, and while my grasp of spiritual things was tentative, I felt that somehow perhaps one might help. So, often – at nights or in quiet moments – I would think of her, wishing her, willing her peace and love and courage with all the strength of my heart. And while I didn't speak of it, I found that she felt and responded to this. In sending love to her this way the ordinary small surface rumplings of disagreement and awareness of each other's small failings completely disappeared, and we felt ourselves very closely united by love in a very real and freeing sense.

One afternoon on a hospital visit, my mother, who had been rather ill, drifted in and out of sleep while I was with her. I sat very close by, cradling her head in my arms, and while she drifted out, wishing her love and peace with all my heart. I nearly trembled with the intensity of effort. At one point she opened her eyes. As I looked at her it was not my mother's hazel eyes into which mine looked, but Bhagavan's deep brown ones. And from them flooded peace and love without measure, unfathomable wisdom and bliss, until everything disappeared into a vastness of love and peace. There was no mother, no daughter, no hospital room – only that profound peace which passeth all understanding.

Slowly – I don't know when – it receded. But at that time I knew that my mother was soon to die, and would pass in peace. And I believed that it would be granted to me to be with her at the end. It took place within a week, and I was by the bedside watching a frail body struggle its last, while strongly aware that its soul watched with me, wondering but unafraid. How deep was my gratitude.

It has not been my privilege to have known Bhagavan while he was among us as a man, nor yet to visit the Ashram or to walk on Arunachala. But Bhagavan, the Ashram and Arunachala are eternally ready to fill me whenever I truly turn my heart and open it to them.

Doubt About Truth

If you have any doubt about the truth, or if you want to support it by your intellectual skill or learned lore, by all means study the several books. But if you have no doubt about the truth and only want to realize it in actual experience, all that trouble is unnecessary. If a cook wants to serve a tasty dish to another, he has to know what thing and how much of each thing go into its composition and how they have to be prepared and mixed in proportion and so on. The person who is asked to relish it need not have that knowledge. So leave the dialectics of our philosophy to the learned among us. You may confine yourself to the practical enjoyment of the peace and joy of the Self.

Austerity

At some point we may wonder what exactly is considered austerity in the light of the teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi. For a clear understanding of this we can be grateful to Arthur Osborne, whose clarity of thought, complemented by his own personal experience, has provided us with this short exposition.

The introduction to "Who am I?" contains within it the germ of the intellectual explanation of religious austerity. Everyone is involved in the unending search for happiness. So long as the person mistakes the body or individuality for the Self, he seeks pleasure from events and contacts, but in the measure that he approaches the true Self, he discovers that true happiness which, being his real nature, requires no stimulus to provoke it.

If a man renounces the extraneous and fitful happiness given by pleasure for the deep, abiding inner happiness, there is no austerity – he is simply exchanging the lesser for the greater, the spurious for the true. More usually, however, a man's pursuit of pleasure (or his hankering after it, even if he does not pursue it) is itself what impedes his realization of the Self, being due to his false identification with the ego. Therefore he normally has to renounce the pursuit of pleasure, not after but before the attainment of eternal, indestructible happiness. This is not because it has ceased to be pleasure but because he realizes, partly through faith and partly through understanding and prevision, that indestructible happiness does exist and is his goal and his true nature and that it is shut off from him by his mistaken identity and by the indulgence of desires and impulses that this entails. That is to say that he has to renounce the false attraction before it has ceased to attract. Therefore the renunciation hurts him and is austerity.

Religious austerity may bear fruit without understanding the intellectual basis of it and there may be many who practise it without this understanding; nevertheless, this is its basis. To some extent every spiritual seeker must follow the twofold method of turning his energy away from the pursuit of pleasure and towards the quest of happiness, away from the gratification of the ego and towards the realization of the Self. They are two complementary phases of one activity. However, a method may concentrate more on one phase or the other.

That taught by Bhagavan concentrated almost entirely on the positive phase, the quest of the Self, and he spoke very little of the negative, that is, of austerity or killing the ego. He spoke rather of the enquiry that would reveal that there was no ego to kill and never had been. This does not mean that Bhagavan condoned ego-indulgence. He expected a high standard of rectitude and self-control in his devotees but he did not dictate any actual program of austerity.

The basic forms of austerity are celibacy and poverty, further heightened by silence and solitude. Let us see in more detail what was the attitude of Bhagavan in such matters.

In speaking of celibacy one has to remember that the traditional Hindu society with which Bhagavan was familiar has no place for the worldly celibate; either a man is a householder or a mendicant. When any householder asked Bhagavan whether he could renounce home and property and turn mendicant, he always discouraged it. "The obstacles are in the mind and have to be overcome there," he would say. "Changing the environment will not help. You will only change the thought 'I am a householder' for the thought 'I am a mendicant.' What you have to do is to forget both and remember only 'I am.'" He similarly deprecated vows of silence and solitude, pointing out that the true silence and solitude are in the heart and independent of outer conditions.

Yet Bhagavan showed a benevolent interest in the personal and family affairs of his devotees – their marriages and jobs, the birth and sicknesses and education of their children, all the cares and obligations that family life entails. His injunction was to engage in it like an actor in a play, playing one's part carefully and conscientiously but with the remembrance that it was not one's real self.

Neither did he denounce the small indulgences common to the life of a householder. Indeed, there was a time when he himself chewed betel and drank tea and coffee. The only specific rule of conduct that he advocated and that some might call austerity was vegetarianism. He spoke of the benefit of restricting oneself to sattvic food, that is to vegetarian food which nourishes without exciting or stimulating. I have also known Bhagavan to say different things to different kinds of people. But they should be taken to suit particular occasions and not as a general rule.

The standard set by Bhagavan was uncompromisingly high but it did not consist in disjointed commands and restrictions. It was a question of seeking the true Self and denying the imposter ego, and in doing this he approved rather of a healthy, normal, balanced life than of extreme austerity. It is true that there was a time when he himself sat day after day in silence, scarcely eating, seldom moving, but that was not austerity; that was immersion in the supreme Bliss after the Self had been realized and there was no longer any ego to renounce, that is, when austerity was no longer possible. His abandoning it was not indulgence of the ego but compassion for the devotees who gathered around. He said that even in the case of the jnani the ego may seem to rise up again but that is only an appearance, like the ash of a burnt rope that looks like a rope but is not good for tying anything with.

Rebirth and the Time Idea

The Maharshi was often questioned about death and reincarnation. He would sometimes answer: "Let us know first who we are" or "The birth of the 'I-thought' is one's own birth, its death is the person's death. After the 'I'-thought has arisen the wrong identity with the body arises. Thinking yourself the body, you give false values to others and identify them with bodies. Just as your body has been born, grows and will perish, so also you think the other was born, grew up and died."

In so many ways Bhagavan tried to bring home to us the true nature of the Self, which is eternal, unborn and free. When an illogical sequence in an apparent death and rebirth were brought to his attention, he would often cite Lila's story from the Yoga Vasiṣṭha. Below are several such inconsistencies recorded in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi. Vasiṣṭha's Yoga, a marvelous prose rending of the book by Swami Venkatesananda, lucidly tells Lila's story, from which a small excerpt is also reprinted for further elucidation

Talk No.129:

An elderly gentleman, formerly a co-worker with B.V.Narasimha Swami and author of some viśiṣṭādvaita work, visited the place for the first time. He asked about rebirths, if it is possible for the linga sarira (subtle body) to get dissolved and be reborn in two years after death.

M.: Yes. Surely. Not only can one be reborn, one may be twenty or forty or even seventy years old in the new body though only two years after death.

Sri Bhagavan cited Lila's story from Yoga Vasiṣṭha.

Talk No.261:

There was a reference to reincarnation. Reincarnation of Shanti Devi tallies with the human standards of time. Whereas the latest case reported of a boy of seven is different. The boy is seven years now. He recalls his past births. Enquiries go to show that the previous body was given up 10 months ago.

The question arises how the matter stood for six years and two months previous to the death of the former body. Did the soul occupy two bodies at the same time?

Sri Bhagavan pointed out that the seven years is according to the boy; ten months is according to the observer. The difference is due to these two different upadhis (limiting adjuncts). The boy's experience extending to seven years has been calculated by the observer to cover only 10 months of his own time.

Sri Bhagavan again referred to Lila's story in Yoga Vasiṣṭha.

Talk No.276:

The U.P.lady arrived with her brother, a woman companion and a burly bodyguard.

When she came into the hall she saluted Maharshi with great respect and feeling, and sat down on a wool blanket in front of Sri Bhagavan. Sri Bhagavan was then reading Trilinga in Telugu on the reincarnation of a boy. The boy is now thirteen years old and reading in the Government High School in a village near Lucknow. When he was three years he used to dig here and there; when asked, he would say that he was trying to recover something which he had hidden in the earth. When he was four years old, a marriage function was celebrated in his home. When leaving, the guests humorously remarked that they would return for this boy's marriage. But he turned round and said: I am already married. I have two wives.' When asked to point them out, he requested to be taken to a certain village, and there he pointed to two women as his wives. It is now learnt that a period of ten months elapsed between the death of their husband and the birth of this boy.

When this was mentioned to the lady, she asked if it was possible to know the after-death state of an individual.

Sri Bhagavan said, 'some are born immediately after, others after some lapse of time, a few are not reborn on this earth but eventually get salvation in some higher region, and a very few get absolved here and now.'

LILA asked:

O Goddess, you said that it was only eight days ago that the holy man had died; and yet my husband and I have lived for a long time [in the present birth]. How can you reconcile this discrepancy? [The "holy man" was reincarnated as Lila's present husband, who had now again just died].

SARASVATI said:

O Lila, just as space does not have a fixed span, time does not have a fixed span either. Just as the world and its creation are mere appearances, a moment and an epoch are also imaginary, not real. In the twinkling of an eye the jiva undergoes the illusion of the death-experience, forgets what happened before that, and in the infinite consciousness thinks 'I am this', etc., and 'I am his son, I am so many years old', etc. There is no essential difference between the experiences of this world and those of another – all this being the thought-forms in the infinite consciousness. They are like two waves in the same ocean. Since these worlds were never created, they will never cease to be: such is the law. Their real nature is consciousness.

Even as in a dream there is birth, death and relationship all in a very short time, and even as a lover feels that a single night without his beloved is an epoch, the jiva thinks of experienced and non-experienced objects in the twinkling of an eye. And, immediately thereafter, he imagines those things (the world) to be real. Even those things which he had not experienced nor seen present themselves before him as in a dream.

This world and this creation is nothing but memory, dream: distance, measures of time like a moment and an age, all these are hallucinations. This is one kind of knowledge-memory. There is another which is not based on memory of past experience. This is the fortuitous meeting of an atom and consciousness which is then able to produce its own effects.

Liberation is the realization of the total nonexistence of the universe as such. This is different from a mere denial of the existence of the ego and the universe! The latter is only half-knowledge. Liberation is to realise that all this is pure consciousness.

"Why should they build here?"

3rd March, 1939

At about 4 p.m. Sri Bhagavan, who was writing something intently, turned his eyes slowly towards the window to the north; he closed the fountain pen with the cap and put it in its case; he closed the notebook and put it aside; he removed his spectacles, folded them in the case and left them aside. He leaned back a little, looked up overhead, turned his face this way and that and looked here and there. He passed his hand over his face and looked contemplative. Then he turned to someone in the hall and said softly: "The pair of sparrows just came here and complained to me that their nest had been removed. I looked up and found their nest missing." Then he called for the attendant, Madhava Swami, and asked: "Madhava, did anyone remove the sparrows' nest?"

The attendant, who walked in leisurely, answered with an air of unconcern: "I removed the nests as often as they were built. I removed the last one this very afternoon."

M: That's it. That is why the sparrows complained. The poor little ones! How they take the pieces of straw and shreds in their tiny beaks and struggle to build their nests!

Attendant: But why should they build here, over our heads?

M: Well-well. Let us see who succeeds in the end. (After a short time Sri Bhagavan went out.)

103rd

Anniversary of

Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi's

Advent

at Arunachala

Sunday 5 September 1999

At the New York Ashrama

The program will begin at 11:00 A.M.

and will be followed by the serving of prasad.

Special Guest

Sri Chinmoy

Founder of the worldwide Sri Chinmoy Centres, will conduct a short meditation, sing the song he composed on Sri Bhagavan and relate his impressions from a visit to Sri Ramanasramam in June of 1999.Arunachala Ashrama,

Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi Center

66-12 Clyde Street,

Rego Park, New York 11374

Tel: (718) 575-3215

Letters

Ethical Practices

Thank you for sending me the picture of Sri Ramana and the booklet "Who Am I?". Can you tell me a bit about ethical practices in this tradition? I am particularly interested to know if you follow traditional precepts of celibacy or more moderate interpretations of brahmacharya? Also, what about things like alcohol? Does the Ashram teach only against alcohol abuse, or is any use of alcohol considered wrong? Finally, I know that Sri Ramana is the ultimate Guru and is considered still extant, but are there other leaders of the Ashram and what is their relationship to devotees? Do they give teachings as well?

Norfolk, VA

As far as ethical living is concerned, the Maharshi never talked much about this subject. The reason is, if we follow his teachings and sincerely try to put them into practice, the correct ethical and moral standards will automatically become part of our character. The essential thing is to begin to practice his teachings with determination and devotion. If that is done, everything will fall into its proper place, and even a teacher will come to us, if and when we need one.

The Maharshi never made a distinction between married or unmarried. He said the Self is the same for all, and real brahmacharya is to abide in Brahman. He did not deny the use of brahmacharya as an aid, like many other aids for spiritual practice.

In our Ashrama, Sri Ramana Maharshi remains as the living Guru. He is the teacher and we are all his disciples. We find that he still responds to sincere seekers, just as he did when embodied. "I am not going away. Where can I go?" he said to grieving devotees before his Mahasamadhi. He continues to respond with his grace and guidance to all those who open their heart to him.

New Books

The following books are three new additions to our 1999 Catalog, which contains about 90 items.

To receive a catalog or make an order, please contact us.

108 Names of Sri Bhagavan

Composed by Sri Swami Viswanathan, and translation and commentary by Prof. K. Swaminathan. These 108 Names of Ramana in Sanskrit ("Ramana Ashtothra") are daily recited with archana before the tomb of the Maharshi. Its daily recitation is a sadhana for many of his devotees. The book contains a the Sanskrit text, the English transliteration and an English commentary for each name.

Sri Lalita Sahasranama

Commentary and translation by C.Suryanarayana, and published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. An ancient scripture on the one thousand

Ramana Maharshi

Amar Chitra Katha, Glorious Heritage of India Series. In thirty pages, the life and teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi is told with colorful illustrations in this popular format. Printed on quality paper, insuring years of use for children of all ages.