His Gaze Met Mine

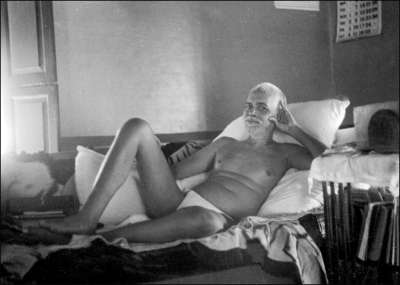

Susri Dhiruben Patel was residing in Santacruz, Bombay when a few devotees, led by Sri Vasant Kothari of Sri Ramanasramam, paid her a visit in May 2007. She is a popular novelist of Gujarat who, like her mother, received guidance and grace from Sri Bhagavan back in the 1940s. Dhiruben Patel had not visited Sri Ramanasramam since the year of Bhagavan's Mahasamadhi, in 1950. Feeling Bhagavan's call, and encouraged by the these devotees to make the pilgrimage to Tiruvannamalai, Dhiruben did travel to Tiruvannamalai later that same year. The text of this article was mostly taken from the video interview recorded during her visit to Sri Ramanasramam in 2007.

My mother, Gangaben Patel, was a freedom fighter and a social worker. She was very badly shaken up along with the whole family at a tragic misfortune that occurred in 1944. My eldest brother met with a drowning accident, which my mother witnessed from the shore. After a few months, Mr. Chhaganlal Yogi suggested that she should go to Sri Ramana Ashram.

At that time we were living in Santacruz, Bombay. When my mother came to Sri Ramana Ashram and saw Bhagavan for the first time, she was so much impressed that she came back to take the whole family to Ramana Ashram. So that is how I, my mother, my father and my newly-widowed sister-in-law came to Sri Ramana Ashram.

Those were the days of World War II, and at Villupuram some British soldiers wanted to get into our first-class compartment, so we were asked to vacate. We were made to lie down on the Villupuram platform the whole night. This was a very bad experience for me. Also, in the morning we got the bus to Tiruvannamalai rather late, so it was almost twilight when we reached the Ashram. I was so tired and so dirty that the first thought in my mind was to go and have a wash and a drink of cold water. But my mother - Oh, she was such a dictator - said, "No. As soon as you enter the Ashram the first thing you should do is to go and have darshan of Bhagavan." I was very reluctant, but those were not the days when children could argue with their parents, so I had to agree and I followed my mother. There I saw the Old Hall where Bhagavan was sitting along with one or two attendants standing nearby. Next to Bhagavan I saw a small vessel in which live charcoals were burning.

At that time I was 18; now I am 81. But I still remember it perfectly. I took that one step up to go into the hall to give my namaskar. I did it like this [she then demonstrates the same type of impatient joining of hands and bow that she made to Bhagavan]. I just wanted to get it finished as soon as possible. I was not interested in Bhagavan or having his darshan. Just because I couldn't defy my mother I had to do it. So with closed eyes, I just did it, and when I raised my head, well - I can't find words to describe what happened to me. As soon as Bhagavan's gaze met mine.he looked at me and in that very second it seemed that I was annihilated. I didn't exist any longer and there was a great sense of release and peace, and there was light, but not strong light. It was like a soft moon- light all around me, with no boundaries and no barriers anywhere. It was as if - I was lost in a sky of light and peace. And I don't know how many minutes or how many seconds I was in that state; it seemed a lifetime. And then, when I came back to my material existence, I just could not accept what had happened.

We stayed five days more and I had darshan of Bhagavan so many times, but that experience was never repeated. It happened only once, but it made me think very deeply and continuously: 'What was it? And how can I be in that state constantly?'

When on the next day we had our bath and sat in the hall along with the other devotees and Bhagavan was there and anybody who wanted to ask a question could ask, I wrote two questions on a piece of paper and handed it over to the attendant. He then told me that I should sit quietly and I will get the answers. But being young and impatient I was unable to wait very long, so after sometime I again bothered the attendant. I told him I was not getting any answers to those questions. It was not working [the silent questioning]. So I went near the couch where Bhagavan was sitting and insisted on getting my answers. Then, Bhagavan gave some answer, which of course I couldn't understand because he was talking in Tamiḷ. There was a person to interpret and I asked him to explain Bhagavan's answers.

Those questions were, first (I had by then read a little of Bhagavan's philosophy, so I asked): "If two persons are lying down and one person has a dream of a tiger and he is frightened and the other person is awake sitting by his side, is it not the duty of the second one to wake up the dreaming person so that he will no longer be afraid? Why doesn't he do it?" That was my first question, to which Bhagavan gave the explanation that the dream state belongs to the person who is asleep and the person who is awake has only to wait for the moment of wakefulness occurring to the person who is sleeping. There is no question of saving the dreamer because there is no tiger.

And my second question was: "Bhagavan, when I look at the mirror for a long time and try to understand who I am, I don't get the answer, but on the contrary I feel frightened looking at my own reflection for a long time. So what should I do?" Then he told me: "Don't look at the mirror, why is it necessary to look at the mirror? Go inwards, think, and find out who you are." This incident happened on the second day of my visit.

After that we stayed for about four or five days more. And, well, being with Bhagavan and noticing his every movement and listening to his voice, I am unable to describe it in words. Being there with him was the most wonderful event of my life. The foremost was when he looked at me and I was transported.

Then the years went by till I came back again in 1950, knowing that Bhagavan was not well and he may not get well. He was on his couch and there was a bandage on his arm and people filed by, single file, going quietly. So, when I came near him I couldn't help saying, "Bhagavan, call me again." Then - with infinite compassion...and immense love - he looked at me. Then he said, "Sari, sari," in Tamiḷ. I didn't understand what that 'sari' meant. Somebody told me later that, it meant "Alright, alright." But it has taken such a long time. I have now come back and I am sure that he has called me back. But I have come after - how many years - fifty-seven years, almost. And I find the Ashram beyond recognition; it has expanded so much. But it's a very strange thing to say that I don't feel the absence of Bhagavan. I feel that he is here. I don't notice his absence. Perhaps it is because during all those years when I was away from Sri Ramana Ashram, I always felt that he was near me. And in my moments of happiness, in my moments of grief, when I was confused, when I felt that I have done something, I have achieved something, all these moments I have at some level communicated with him. And, I have received his grace, and now know that I am not the only individual who has. He has done this to everybody, the whole mankind.

When you are really facing a big problem or have some big question and you don't know where to turn or what to do, then Bhagavan really gives the answer in your heart of hearts.

I shall have to tell about a nephew of mine who was only two years old when he came here with my Mother. Bhagavan, as usual, was going for his walk after lunch on the hill, and all devotees were standing in a line. This boy, my nephew, also was there. Suddenly he saw Bhagavan and he ran to him and held his walking stick so firmly that he wouldn't allow Bhagavan to budge. Everybody was aghast watching this and requested the child to go away and not to bother Bhagavan. But he didn't listen. And for a long time he went on staring at Bhagavan. Bhagavan put his hand on his head. At once he let go of the stick and he started weeping - not loudly, but tears were streaming down his eyes while he just stood looking at Bhagavan.

This same nephew of mine we, unfortunately, lost three years ago, in 2004. When he was not well and in the hospital he used to tell me everyday, "Foie [Auntie], do you know what we are going to do as soon as these doctors leave me and I am able to go out?" I said, "I don't know." He said, "We will go to Ramana Ashram. That will be the first thing we will do. And only you and I will go there."

Now, physically, it is not possible because he is not here. So I thought that it is now my duty to go to Ramana Ashram. I thought that I will go alone, I will stay there and I will find out if Bhagavan's presence is still felt. Whether I am here or whether I am there, or whether I am anywhere, I tell you I feel that Bhagavan is with me always. And that is all due to the first wonderful moment when he looked at me.

My mother used to rent a cottage here and stay for two or three months at a time. She was such a sincere soul and a self-educated woman. She had very little school education, hardly two or three years. Nevertheless, she learnt Hindi, English, Sanskrit and wrote in Gujarati. But when she came here she found that all this was no use because Bhagavan used to talk mostly in Tamiḷ and rarely in English. But my mother had such an irresistible attraction towards Bhagavan and his teachings. She used stay here and meditate very regularly, in spite of all the other work that she was doing. What happened to her here, what she experienced, she spoke little.

One thing I can tell you is that once she suffered from a paralytic stroke and was not able to speak at all. After a month and half, gradually her speech began to come back. But then, it was not fluent and we could not understand all the time. For example, if she wanted her shoes, she will ask for soap and then would sometimes get annoyed because we couldn't understand her. Everybody was depressed about this and we felt sad that such a wonderful person as my mother may have to end her life in this condition. All of a sudden I remembered the evening parayana of "Upadesa Sarah" and recited one or two lines before her. My mother was at once alert and picked up the recitation and concluded the thirty verses without a single mistake or single faltering. After this she was able to recite Bhagavan's works and slowly she then became normal. She wrote her autobiography also.

In her last illness she made me promise that nobody should weep when she goes and also that Bhagavan should be with her, and that I am the one responsible for these requests. She insisted that I must do this. So I replied, "How can I do that? Who knows which is going to be the last minute in a person's life?" Still, she made me promise. And by God's grace and Bhagavan's blessing it so happened.

During her last moments I was there and this nephew of mine held a very big framed photograph of Bhagavan before her eyes. She quietly gazed at the photograph and then turned her eyes and passed away.

For various reasons, sometime after Bhagavan's passing, for about two or three years, my heart was full of agony. I had not studied Sanskrit scriptures or anything like that and so thought 'How can I find somebody who will teach me.' By great good luck, in Mount Abu, I came across Sri Gangeswaranandji Maharaj who accepted me as one of his pupils. He taught me everything and gave spiritual guidance also. But whenever somebody would ask him if I was his disciple, he would say, "No. She is the disciple of Ramana Maharishi, but she is my daughter and I am helping her."

And in many ways such as this, I have always felt Bhagavan's loving presence.Once You Experience the Self,

You Are Held By It

I have had opportunities to talk to Bhagavan and one of them I mention here. One day I went to see Gurumurtham and the garden near it. These two places are well known to those who have read his biography. It was in this garden that Bhagavan's uncle recognized him as his nephew Venkataraman, who had left his home some three years earlier. After visiting the two places, I returned to the Asramam and told Bhagavan that the place now was more or less an open ground and was not a garden as described by Narasimha Swami in his book Self Realization. Bhagavan immediately began to describe how the garden had been then and proceeded further to describe his life during his sojourn there. He said that he was taking shelter in a lamb pen where it was hardly high enough for him to sit erect. If he wanted to stretch his body on the floor, most of it would be out in the open. He wore only a koupina and had no covering over the rest of his body. If it rained, he remained on the wet and sodden ground where sometimes water stood a couple of inches deep! He did not feel any inconvenience because he had no 'body sense' to worry him. He felt that sunrise and sunset came in quick succession. Time and space did not exist for him! He then tried to describe the state of his awareness of the Self and his awareness of the body and things material. To him, the sun of absolute Reality made the phenomenal world disappear and he was immersed in that light which dissolves diversity into the One without a second!

It is not possible to express exactly the thrill felt by all of us who were listening to him. We all felt transported into that condition for which we are striving. There was a deep silence in the hall for some time and everyone present felt peace and happiness. It occurred to me then that Bhagavan, while narrating any incident of his life, was taking the opportunity to teach us, and I told him that when he spoke we felt as if it were easy to experience the Self and as if we had glimpses of it. We asked him exactly how one has to proceed to be in that state of continuous awareness which he had described. Bhagavan, with his sparkling eyes, looked at me benevolently, raised his hands and said:

"It is the easiest thing to obtain. The Self is always in you, around you and everywhere. It is the substratum and the support of everything. You are experiencing the Self and enjoying it every moment of your life. You are not aware of it because your mind is on things material and thus gets externalized through your senses. Hence, you are unable to know it. Turn your mind away from material things which are the cause of desires, and the moment you withdraw your mind from them you become aware of the Self. Once you experience the Self, you are held by it, and you become 'That' which is the One without a second."

When he finished his words I again felt as I had felt on the first day I met him - that Bhagavan is a big powerhouse and his power or grace overwhelms us, whatever our ideas may be, and leads us into the channel flowing into the Self. It became clear to me that we can have the knowledge of the Self if only we take the path on which a realized person or guru directs us.

In conclusion I wish to say that one should constantly meditate that one is not the body or the mind. Unless the mind is in contact with the senses, we cannot get any report from our ears, eyes, etc. We must therefore still the mind by disconnecting it from the senses and thus get beyond them to experience the Self. What we learn from sense perception is only relative knowledge. Knowledge of the Self can be learnt only by sitting at the feet of one who has realized it; what others tell you is mere talk. Bhagavan Ramana is one of those Masters who has realized the Self and like all other Masters who preceded him, he helps us proceed rapidly to attain Self knowledge."There are two Mahans in our country. One is Ramana Maharshi and the other Gandhiji. The Maharshi gives us Peace. Gandhiji does not allow anyone to remain in peace. Both do so for the same reason, for the spiritual freedom of India.

Children's Ashrama

Do you want to hear about my Nova Scotia camp?

We landed in Halifax on Saturday, July 27th. Dennis Maama picked us up. We took a three-hour drive to the Ashram. First he showed us the temple. There I met a wonderful dog named "Lucky"! Next we went to the house and he showed us our room. In the house I met another dog named "Sofia". I love dogs and was very happy to meet Lucky and Sofia. The Ashram also has two cute goats, Meena and Chadwick.

The camp started on Monday. We had so many fun activities. We did "Beach Sweeping" where we cleaned up the beach on the Bay of Fundy. We went to the top of a lighthouse near the beach. We hiked up the mountain behind the Ashram and sang songs inside a cave where we found the bones of some dangerous animals! Kevin gave me some racoon bones. Horseback riding was a lot of fun. On Wednesday we went to a swimming pool and played water polo. Thursday was the best. We went to Keji National Park on a picnic and did canoeing, hiking and swimming there. Karma yoga was so cool! Kevin taught us to take turns moving stones and we put them on the basement floor.We got to exchange positions, which is what I enjoyed most.

The camp teachers were great. Geeta taught us yoga. Darlene taught us songs. My favorite song was "In My Heart, Arunachala...."[1] Kevin taught us stories and games. On the last day we did some skits and had a campfire.

[1] from the 'Arunachala" album by 'Yamuna'

I've been to all seven of the Nova Scotia Ashram children's camps. This one was very fun because with only six campers I was able to get to know each and every camper. In the past we had at least ten to twelve. We did lots of fun activities like horseback riding, swimming, canoeing, hiking. Also, we hiked up the hill to the Ashram's Virupaksha Cave. Every morning we would have meditation sessions, where we learned the basic skills of meditating. This was followed by stories of Bhagavan's kindness towards all living things, people, animals and trees, etc. At the end of the camp we chose four of the thirteen stories the counselors told us and acted them out as skits for the parents. Each day we did Karma Yoga, where we used teamwork in the form of a bucket brigade to cover the basement floor with stones. Some campers in particular liked this activity because they felt it was a good way to give back to the camp. We learned to work without any personal gain.

There was one camper in particular who liked horseback riding. He seems to be a natural with animals, the Icelandic horses at the riding center, our two goats Meenakshi and Chadwick>, and also with the two main attractions of the camp, the dogs, Lucky and Sophie. There were a few campers who liked hiking up to Virupaksha cave the most. We found some bones in the cave. While in the cave we sang some Ramana songs. A few of us ran down the mountain as fast as we could, to give us some extra free time, while others came down slowly.

Everyone liked Keji Park because there was an activity for everyone. I found that the highlight of the day was the ice cream parlor, which was a nice refreshment after all the great activities we did, such as canoeing (or trying to canoe), picnicking and swimming in the lake.

One story that was automatically selected to be acted out was "Mr K. and the Coconut Tree." Mr K. was cutting down coconuts with an iron sickle when Bhagavan came and asked him to use a bamboo sickle, in order to not hurt the trees. He ignored Bhagavan's advice and continued using the iron sickle. Later that day one of Bhagavan's attendants came running to him and told him how Mr. K. had been hit on the head by coconut that fell off the tree. Bhagavan said he was sorry Mr. K. had been hurt, but by now he would have learned his lesson and knows how much pain the tree is in when it is cut with an iron sickle.

All in all, we had a very good camp except for the lack of sleep. I know all the campers had a great time and hopefully will be able to come back next year.

The Path of Enquiry

Self-enquiry is not analysis; it has nothing in common with philosophy or psychology. The Maharshi showed this when he declared that no answer the mind gives can be right. (And, indeed, in this it resembles a Zen koan). If it had a mental answer it would be a philosophical conundrum, not a spiritual practice; and it was as a spiritual practice that the Maharshi prescribed it. So anyone who tells you what the answer to the enquiry is shows by that very fact that he has not understood it. It does not mean arguing or saying that I am not this or not that; it means concentrating on the pure sense of being, the pure I-am-ness of me. And this, one discovers, is the same as pure consciousness, pure, formless awareness.

So far is it from being a mental practice that the Maharshi told us not to concentrate on the head while doing it but on the heart. By this he did not mean the physical heart at the left side of the chest but the spiritual heart on the right. This is not a physical organ and also not a yogic or tantric chakra; but it is the centre of our sense of being. The Maharshi told us so and those who have followed his instructions in meditation have found it to be so. The ancient Hebrews knew of it: "The wise man's heart is at his right hand, but a fool's heart is at his left," it says in the Bible. It is referred to also in that ancient Advaitic scripture, the Yoga Vasiṣṭha, in verses which the Maharshi quoted as Nos. 22-27 in his Supplementary Forty Verses on Reality. Concentration on the heart does not mean thinking about the heart but being aware in and with the heart. After a little practice it sets up a current of awareness that can actually be felt physically though far more than physical. At first this is felt in the heart, sometimes in the heart and head and connecting them. Later it pervades and transcends the body. Perhaps it could be said that this current of awareness is the 'answer' to the question 'Who am I?', since it is the wordless experience of I-ness.

There should be regular times for this 'meditation', since the mind accustoms itself and responds more readily. I have put the word 'meditation' in inverted single quotes, since it is not meditation in the usual sense of the word but only concentration on Self or on being. As Bhagavan explained: "Meditation requires an object to meditate on, whereas in Self-enquiry there is only the subject and no object." Good times are first thing when you wake up in the morning and last thing before going to sleep at night. At first a good deal of time and effort may be needed before the current of awareness is felt; later it begins to arise more and more easily. It also begins to occur spontaneously during the day, when one is not meditating. That explains Bhagavan's saying that one should keep up the enquiry constantly, not only during meditation. It comes to be more and more constant and, when lost or forgotten, to need less and less reawakening.

A man has three modes of manifestation: being, thinking and doing. Being is the most fundamental of the three, because he can't think or do unless he first is. But it is so covered over by the other two that it is seldom experienced. It could be compared to the cinema screen which is the support for the pictures without which they could not be seen, but which is so covered over with them that it is not ordinarily noticed. Only very occasionally, for a brief glimpse, does the spiritually untrained person experience the sheer fact of being; and when he does he recalls it afterwards as having been a moment of pure happiness, pure acceptance, pure rightness. Self-enquiry is the direct approach to conscious being, and therefore it is necessary to suspend thinking and doing while practising it. It may lead to a state when conscious (instead of the previous unconscious) being underlies thinking and doing; but at first they would interrupt it, so they have to be held off.

This is the path; the doctrine on which it is based is Advaita, non-duality, which might be rendered 'Identity' or 'No-otherness'. Its scripture for the Maharshi's followers is his Forty Verses on Reality together with the Supplementary Forty Verses which he later added.

In this he declares: "All religions postulate the three fundamentals; the world, the individual and God."

Not all in a formal way, for there are also non-theistic religions; but essentially this is what we start from. Whether I am educated or uneducated, my own existence is the basis from which I start, the direct awareness to which everything else is added. Then, outside myself, my mind and senses report a world of chairs and tables and trees and sky, and other people in it.

Mystics tell me that all this is illusion, and nowadays nuclear scientists agree with them. They say that the red book I am holding is just a cluster of electrons whirling about at high speed, that its redness is just the way my optic apparatus interprets a vibration of a certain wavelength, and similarly with its other qualities; but anyway, that is how it presents itself to my perception. I also have a feeling of some vastness, some power, some changeless Reality behind the vulnerability of the individual and the mutability of the world. It is about this third factor that people disagree, some holding that it is the real Self of the individual, others that it is a Being quite other than him and others again that it does not exist at all.

The verse continues: "But it is only the One Reality that manifests as these three." This implies that Self-enquiry is the quest for the one Reality underlying the apparent trinity of individual, world and God.

But the mistake inherent in dualism does not consist in supposing that God is a separate Being from you but in supposing that you are a separate being from God. It is not belief in God that is wrong but belief in the ego. Therefore the verse continues: "One can say, 'The three are really three only so long as the ego lasts'." Then the verse turns to the practical conclusion, as Bhagavan always did in his teaching: "Therefore, to abide in one's own Being, where the 'I' or ego is dead is the perfect State."

And that is what one is trying to do by Self-enquiry: to abide as the Self, the pure Being that one essentially is, casting aside the illusory reality of the ego.

Feeling one's insignificance before that mighty Power, one may worship It in one of Its manifestations . as Krishna, say, or Christ or Rama, but: "Under whatever name and form one may worship the Absolute Reality, it is only a means for realizing It without name and form." That means appreciating Its Infinity, realizing that It alone is, and leaves no room for a separate me subsisting apart from It. Therefore the verse continues: "That alone is true Realization wherein one knows oneself in relation to that Reality, attains peace and realizes one's identity with It."

And this is done by Self-enquiry. "If the first person, I, exists, then the second and third persons, you and he, also exist. By enquiring into the nature of the I, the I perishes. With it, 'you' and 'he' also perish." However, that does not mean blank annihilation; it only means annihilation of the illusion of separate identity, that is to say of the ego which is the source of all suffering and frustration. Therefore the verse continues: "The resultant state, which shines as Absolute Being, is one's own natural state, the Self."

Not only is this not a gloomy or dismal state or anything to be afraid of, but it is the most radiant happiness, the most perfect bliss. "For him who is immersed in the bliss of Self-realization arising from the extinction of the ego what more is there to achieve? He does not see anything as being other than the Self. Who can apprehend his State?"

Note that in speaking of the unutterable bliss of Self-realization Bhagavan says that it is achieved through the extinction of the ego, that is the apparent individual identity. So that, although nothing is lost, something does have to be offered in sacrifice; and while being offered it appears a terrible loss, the supreme loss, one's very life; only after it has been sacrificed does one discover that it was nothing and that all has been gained, not lost. This means that understanding alone cannot constitute the path. Whatever path may be followed, in whatever religion, the battle must be fought and the sacrifice made. Without that a man can go on all his life proclaiming that there is no ego and yet remain as much a slave to the ego as ever. Although the Forty Verses on Reality is a scripture of the Path of Knowledge, Bhagavan asks in it: "If, since you are a single being, you cannot see yourself, how can you see God?" And he goes on to answer: "Only by being devoured by Him."

— From Mountain Path, Vol. 2, 1968