Activity, Help Not Hindrance

by Viswanatha Swami

THE earnest aspirant is endowed with onepointedness of mind. But others, whose minds are restless on account of their attachment to the outer world, are asked to practise certain simple spiritual disciplines in order to acquire the concentration of mind which is an indispensable step towards ultimate spiritual attainment.

The urge to be active is strong in man; it is extremely difficult to renounce action altogether and dedicate oneself entirely to spiritual sadhana, whatever be the mode of sadhana.

Thus, of all the paths available for an aspirant, Karma Marga is the most suited to the modern age. By Karma Marga we do not mean the rituals of the orthodox or social service as generally understood nowadays. By Karma Marga we mean the performance of one's svadharma as determined by one's environment and circumstances. Since action is inescapable, the choice left for one is to follow one's svadharma without undue attachment to the results.

What is this Karma Marga pursued merely as doing one's svadharma? It is simply working in an egoless spirit without identifying oneself with the doer. But such egolessness is impossible for the man of the world; he always identifies himself with the doer. Karma Marga then is the process of inner development which enables one to be active in the world and yet remain unattached to the credit or the results of the work. The sadhana consists in cultivating the attitude that it is not oneself that acts but a Power within. "Doership pertains to the individuality; but you are not a separate individual and so you are not the doer. "Man is moved by some mysterious power but he thinks he moves himself," says Sri Bhagavan. The same idea is conveyed in the Bhagavad Gita (XVIII, 61): "Mounted as on a machine in the heart of every being dwells the Lord whirling every being by His mysterious power."

The urge for action is strong in most men; action is their svabhava; it is impossible for them to renounce all activity. But the distinguishing characteristic of the karma yogi is that throughout his activity he feels intuitively that he is not the doer, but that the higher power works through him. He is thus merely an instrument of the higher power working for the welfare of all. His work, therefore, is really worship. He asks nothing for himself, seeks nothing, but yet is active. He realizes that he is only an actor playing his role in the drama of life, the Lila of the Supreme. He does not forget his real Being nor does he overplay his role to win fame or personal success. There is no room for desires in him because of his non-identification with a petty individuality. Such a detached life frees him from the prison of ignorance, though he may be active like others.

Is action, without expectation of results, itself enough? Detached action (nishkama karma) is the means to achieve inner purity and therefore one has to strive further in the quest for perfection. The question still persists: who is engaged in such nishkama karma? As long as there is a doer there is the need for the experience of pure non-dual Awareness. Hence the karma yogi too has to tread the path of knowledge ultimately. But Self-enquiry comes naturally to him. The perfect karma yogi is spontaneously drawn to the path of jnana (knowledge). The apparently contradictory paths of karma and jnana become complementary and inseparable from each other. The purity of mind brought about by selfless action points the way to jnana.

The identification of one's true Being with the body-bound ego is the root cause of all selfishness and suffering. Such wrong identification ends only with the dawning of wisdom through the enquiry: 'Who is bound?', 'Who am I?'. When, through uninterrupted experience of Being, the wrong notion of bondage (and liberation therefrom) is dispelled, the radiance of Pure Awareness alone remains. Sri Bhagavan has clarified for us the path of Self-enquiry starting from selfless action and culminating in the bliss of Pure Awareness.

Inner search for jnana together with such disinterested karma is the most practical way for most of us under the present modern conditions. Leading such a life is fully approved by Sri Bhagavan when he says: "Leave your outward life to prarabdha and make intense effort within for illumination." He has taught us that, while pursuing the path of Self-enquiry, we can carry on our occupation in life, without the least idea of 'I am doing this'. The idea 'I am the body' is the only ignorance and bondage. Performing our work with detachment and enquiring 'Who Am I?' at the same time is the safest course for release from bondage. To do one's work impersonally and to enquire intensely within 'Who am I?' is thus the essence of the teaching of all great Masters.

Bhagavan sums this up aptly: "A man need not give up his worldly duties; what he should give up is desiring things for himself." The ideal to be aimed at, therefore, is a life of selfless activity accompanied by uninterrupted awareness. The mind that operates without attachment to its own past or future can efficiently attend to any kind of work in a truly scientific manner. Such a mind is well protected from all ignorance and distraction as it is free from petty, personal desire.

It should be remembered that Sri Bhagavan's method is not a mere intellectual exercise, but a heuristic and holistic sadhana for self-integration and self-transcendence in which there can be no conflict between awareness and action. The only freedom we enjoy and the only obligation enjoined on us is to turn the searchlight inward and learn to look within. Having once set out on this quest of self-improvement through Self-enquiry, one can no more miss one's way than a living plant firmly rooted in good soil in the open air can lose its rapport with sunlight. One's very means of livelihood, the actions that one is called upon to perform, duty to family and role in society, will undergo the requisite change, either through one's volition or by sheer force of circumstance. All things work together for good to them that love God, i.e., for those who have turned towards the Self. For turning to the universal Self is ceasing to be selfish, narrow, and personal. The more impersonal the worker, the more scientific and more efficient the work. If disinterestedness is an asset, surrender to the Lord, heightened awareness and empathy with one's fellow workers, add a new dimension to one's human relations.

The spiritual aspirant who is honest and heroic can, therefore, use even worldly work as a means of self-purification. This may even be easier than it is for an inmate of an ashram who fails to maintain the right attitude to activity, which can be a hindrance in the spiritual path.

There is a lurking fear in some people that their sadhana will be adversely affected by engaging in work or service. Even granting that sadhana becomes less intense if combined with work, can one honestly assert that one is engaged in sadhana all the time? Unfortu- nately the truth is far from this. People who are not prepared to be active in constructive work mostly indulge in casual or loose talk, controversial discussion or even outright gossip. Their own notions of piety also drive them to undertake minor or major jobs for others. The results of such undertakings of individual responsibility are unpredictable. Thus the problem comes through the back door and has to be faced. It is far better and safer to do allotted tasks than indulge in erratic activity. Rare is the sadhaka who can carry on sadhana on a whole time basis. And it is highly unlikely that such a person will refuse to do service when called upon to do so.

The human tendency that drives one to activity cannot be wished out of existence. This tendency can be sublimated by accepting work or service as a vita and recognized aspect of spiritual practice.

Work, particularly systematic work, has rich rewards. In the higher, spiritual sense, gradual purification results. Work in an impersonal and universal cause helps the erosion of the ego. The loss of individuality is easier here than in mundane activity where personal motives have wider and stronger play. The two types of activity are different. Work in the world without is a sadhana for the athletic spirit. Work in an ashram demands less of courage than humility.

Spiritual alertness and physical briskness go together. Spiritual laziness can lead to physical laziness and vice versa. Spiritually evolved persons prove the poin conclusively. Sri Bhagavan was always an enthusiastic participant in the Ashram chores. He was the first to ge up (from his apparent sleep) and attend to kitchen duties like cutting vegetables. He did this for many years. He had done on numerous occasions jobs like brick laying and book binding. There was no task which he deemed beneath him. Apart from this personal example there was also his unmistakable admiration for those who worked hard for the Ashram. His own Ashram on the Hill he named Skandashram, because one Kandaswam cleared the ground and prepared the site for it single handedly. For the dignity of useful labor there could be no higher testimony than the example of Sri Bhagavan.

This does not mean that ashrams should be converted into workhouses and their activities expanded in a mechanical manner. But one should not attempt to escape work that needs to be done; one should do one's share of it willingly. The kind and quantum of work done does not matter as much as the willingness and zeal one puts into it.

It should never be forgotten that awareness is our true Being and that action is only a ripple, a movement, a shadow in the ocean of awareness. We should not be in too great a hurry to become agents, we should for the most part be content to be patient. As Wordsworth says:

Action is transitory, a step, a blow,

The motion of a muscle, this way or that,

'Tis done, and in the after vacancy

We wonder at ourselves like men betrayed. Suffering is permanent, obscure and dark And shares the nature of infinity. Whatever action we do, and none of us can altogether escape action, whether in the world or in an ashram, should be surrendered to the Lord, should not boost the ego and should thus help inner purification. In the words of Herbert:

Who sweeps a room as for Thy laws

Makes that and the action fine.

It is in this spirit that Appar, the saint who was ever busy tidying up our temples and their environs, sang of the covenant between him and Siva

My duty is Only to serve and be content.

An Invitation

to join us in celebrating

The 128th Jayanti of

Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi

inNew York City

Sunday 11 January 2009 11:00 a.m.

atArunachala Ashrama

86-06 Edgerton Boulevard

Jamaica Estates, Queens, New york 11432-2937

The program will include recitations, bhajans, talks and

puja, followed by prasad (lunch).

For more information contact: Arunachala Ashrama

Reminders

by Prof. G. V. Subbaramayya

The author of the following arcticle was sincere, moved with childlike familiarity with the Master, and experienced His grace in full measure. He has written about his experiences in the captivating book, Sri Ramana Reminiscences.

LET me recall some indications by Bhagavan that will help to keep the aspirant on the right path, safe from pitfalls. Such reminders are necessary lest, with the passage of time, the clarity of his teaching gets blurred.

The final aim and purpose of all sadhana — fasts, prayers, pilgrimages, penances, etc. — is, he reminded us, to annihilate the ego through perfect control of the mind and thereby to realize the true Self. This should be always borne in mind lest the aspirant get too attached to his technique and mistake it for the purpose when it is only the means. Any sadhana is only a road to reach the destination and never a residence.

The practice of Self-enquiry is the direct method since it directly tackles the mind, but it does not exclude other practices, which may suit the particular aspirant owing to his samskaras or predispositions due to prarabdha or previous destiny. All sadhanas lead to the same goal.

When we speak of Self-realization, it is to be remembered that the Self is not some wonder that will drop down from the heavens before our gaze. It is not anything outside us or anything perceptible to the mind or senses. It is the real Self or I that every one of us is in fact. Therefore, Self-realization is only being what we are. This comes about on transcending the dualities (good and bad) and triads (knowledge-knower-known), when the unreal accretions of the mind disperse.

Self-enquiry is not a catechism or a mental process of question and answer. The question 'Who am I?' is not intended to provoke an answer such as 'I am this' or 'I am that' but is only a means to still the mind. When a thought arises one is not to pursue it but to ask oneself to whom it occurs. The answer is 'to me', and this provokes the further question, 'Who am I?'. With this the first thought disappears.

The mind is nothing but a bundle of thoughts that incessantly arise. If the above process is repeated every time a thought arises all thoughts vanish and the mind dwells solely on the basic I-thought. With sufficient practice it gets rid of its thought content and becomes transformed into the real 'I' or true Self which shines continuously of its own accord. The aspirant's effort terminates in complete stilling of the mind. What follows is automatic like the sun's shining after the clouds have passed.

Since the real Self is the repository of all power, as of everything else, the aspirant, in his quest for the Self, may or may not acquire powers or siddhi. This is dependent on his prarabdha or self-made destiny. In a realized Man these occur unsought and manifest themselves naturally. For an aspirant to seek them or make use of them deliberately is harmful; it is likely to strengthen his ego and thereby hamper his spiritual progress. The right attitude for him is to remain indifferent whether they come or not and concentrate on Self-realization.

There is no contradiction between so-called 'worldly' life and spiritual practice. We can remain in society, practising any trade or profession, and at the same time remember all along what we really are. We should not identify ourselves with our body senses or mind but remember that we are the all-pervading Spirit.

Either we surrender to the Supreme Spirit, Self or God, by whatever name we may call It, or go on enquiring what we really are until we realize our identity with It. Not only are professional work and spiritual effort not contradictory but the latter helps to perfect the former and even makes it a means of self-purification, which is a prerequisite of Self-realization.

In conclusion, let us never forget the greatness and glory of Sri Bhagavan. At the age of seventeen He attained Self-realization by spontaneous effort, with no instruction and no outer Guru. The remainder of his life was only a leela or 'play' in which the Supreme manifested its Grace by radiating his Glory and diffusing Peace and Bliss around that 'Mighty Impersonality', as the poet Harindranath Chattopadhyaya once called Bhagavan (when someone else had been called a 'mighty personality'). The term 'Bhagavan' is sometimes used as a honorific title for holy personages but Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi is Bhagavan in the fullest sense of the word. Glory to Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi!

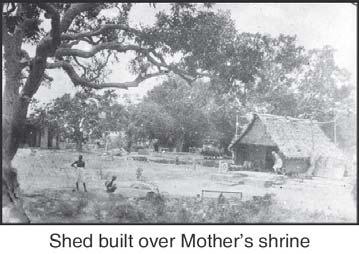

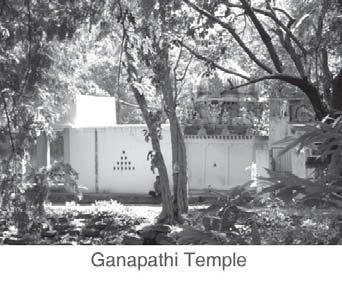

A Haven Called Palakothu

Until 1922, the place where Sri Ramanasramam and Ramana Nagar are now located was covered with cactus and scrub bush, and was unfrequented by people. On 20th May, 1922, the bush and the cactus were cleared to make way for Mother's samadhi and the thatched shed which covered it. After Bhagavan came down from Skanda Ashram and settled down here, it blossomed into Sri Ramanasramam. At that time, except for the thatched shed and the Ganapathi temple in Palakothu, there was no place where one could stay.

Sabhapathi Pillai used to come and do puja to Ganapathi. Opposite the temple, there were two small rooms. One was used by Pillai and the other was used by Kavyakantha Ganapathi Muni. Incidentally, the Muni who was staying in the Mango Tree Cave, shifted to Palakothu to be nearer Bhagavan. It was also cooler under the shade of the trees. Kavyakantha used to eat and sleep there and spend the rest of the time in the presence of Bhagavan. He was the first to stay very close to the Asramam. After him, Swami Suddhananda Bharati spent some time in the room.

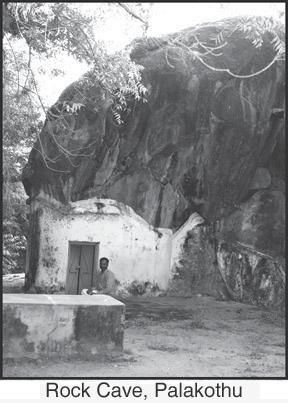

When the Ashram expanded a little,

B.V.Narasimha Swami

reconstructed the rock cave in

Palakothu

so that he could live in it. This was close to the Ganapathi Temple in Palakothu. He also built a small cottage and prepared his food in a cooker and lived a quiet life having darshan of Bhagavan.

During his stay he wrote the book

Self-Realization.

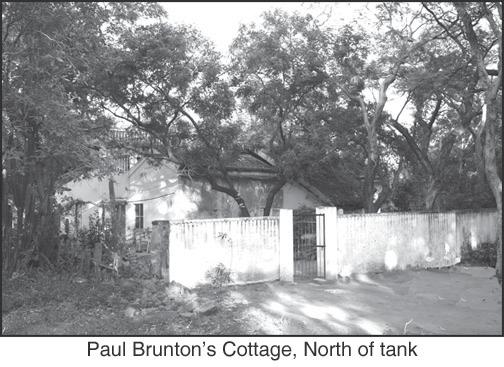

Among the first westerners to come and stay at the Ashram were Paul Brunton and Bhikshu Prajnananda. They constructed for themselves a two-room cottage to the north of the tank in Palakothu. Later Musiri Krishnananda put up a thatched shed to the north of Timma Reddi of Andhra and Sachidadanandaswami of Kerala also constructed cottages close to Krishnananda's. To the south of the tank, Mudaliar Granny's son, Thambiranswami, put up a tiled house. The disciples of Ma Anandamayi, Prabuddhananda and Bhumananda, built a small house next to Thambiranswami's. Next to that, Somasundaraswami built a cottage. He was looking after the bookstall.

After B.V.Narasimha Swami left, his 'cave' was occupied by Yogi Ramaiah and after him by Mouni Srinivasa Rao. Later Bhagavan's attendant Krishnaswami was the last devotee to live there. Into another cottage of B.V.Narasimha Swami built, Viswanatha Swami after Narasimha Swami left. Muruganar moved into Musiri Krishnananda's cottage and Munagala Venkataramayya moved into Tiamma Reddiar's cottage. After Venkataramayya, Swami Satyananda, who served Bhagavan as his personal attendant in the late 1940s, stayed there. He handed it over to Kunju Swami when he left. Kunju Swami stayed in it for a number of years. Paul Brunton and Bhikshu Prajnananda also stayed in this cottage for some time. Now a German lady by name Helga is staying there after repairing it. She has also renovated the Ganapathi temple in Palakothu and arranged for the performance of its Kumbabhishekam.

When Muruganar, Viswanatha Swami, Munagala Venkataramayya, Sachidanandaswami and Kunju Swami were at Palakothu, there was Ramanatha Brahmachari with them. He was very gentle and innocent and was keen to serve others. He would buy vegetables for the devotees in the market in town and bring kerosene donated by a devotee. He would clean the lamps in the rooms, fill them with kerosene, sweep the rooms, etc. His was selfless service. The devotees called him Sarvadhikari of Palakothu.

After Annamalaiswami left the Ashram, he built his cottage in Palakothu. As years past, he built additional cottages for visitors. His land was eventually given over to the Ashram, along with other residences occupied by disciples of Bhagavan. The Ashram property now stretches westward into the previous area called Palakothu and well up to the tank. What remains of Palakothu is a quiet place with a small forest, reminiscent of the early days of Ramanasramam.

How My Father Came to the Maharshi

By the Musician Kovai-Mani

MY father's spiritual life started in his boyhood when he had darshan of Lord Siva in the guise of an old man. This continued to carry him further and further till it induced him to resign his job at Alleppey in Kerala and plunge into the ocean of spiritual quest. He then took to a wandering life, visiting shrines and holy places of South India, together with his wife. This was long before he came face to face with Bhagavan. He was able to maintain himself on his wanderings, being a musician who gave harikirthanas. He and his wife had a number of thrilling experiences which proved that the Lord is indeed One and pervades everywhere.

In 1928, he settled at Coimbatore and in 1930 I had the good fortune of being born as his son. Often poverty stared him in the face, but he never actually lacked food. When the last meal was finished and he was left wondering about the morrow the next would appear, but only the next. Many sadhus used to visit him, directed by Providence, either as a means to strengthen his faith or to test his strength.

It was in 1933 that he first went to Tiruvannamalai, with the hope of earning something. He felt a desire to see the person he had heard spoken of as 'the Maharshi'. Bhagavan was going through some papers when he first saw him. After a while he raised his head, shaking slightly as usual, and beckoned my father to approach. Hesitant at first, but then convinced that he was calling him, my father went up to Bhagavan and prostrated. "So you have come from Coimbatore? And how is the family?" Bhagavan said, showing, as he sometimes did, knowledge of the circumstances.

"Wait a little," Bhagavan said, and in that 'little' wait, Nilakanta (my father) was caught as in an eternity. "Come let us go to the hall," Bhagavan said, tapping him. Without a word, Nilakanta got up to follow him but then, with a sudden shock, he saw the Divine Father walking in front of him. Unable to control himself, he cried out "Appa!" (Father). By that time Bhagavan had turned into the doorway of the hall and Nilakanta, hurried after him, beholding the God Subrahmanyam ahead of him. Before he had time to think, Bhagavan was in the hall and motioned to him to sit on his right at the foot of the couch. There he sat, feeling like a child at the feet of his father. The minutes ticked by. People were coming in, asking questions, prostrating, but Nilakanta was oblivious of all this. Then the lunch gong sounded and people got up and went out as usual, taking it for granted that Bhagavan, who was always punctual, would go too. But he did not get up. Nor did Nilakanta. Nilakanta heard a silent voice asking him: "What do you want?" And silently he answered, "Grace." Still neither of them moved. Nilakanta did not even look up at Bhagavan. Suddenly he felt a hand on his shoulder and, looking up, he saw the Sarvadhikari who whispered, "Bhagavan won't get up unless you do. People are waiting in the dining hall."

Nilakanta looked up and saw Bhagavan's usually shaking head as firm as a rock while, through half-closed eyes he was bestowing on him a penetrating look[1] of boundless love and grace! Surrounding Bhagavan's head was a golden halo the size of an umbrella inside which golden light-waves emanating from Bhagavan's head were radiating. Nilakanta forgot everything. In one leap he was at Bhagavan's side and had flung his arms round him. In a voice husky with love he said: "My Father, your devotees are waiting for you. Shall we go?"

"Is that so?" Bhagavan immediately replied. "Yes, of course we will go." And he left for the dining hall followed by Nilakanta.

My father told me that after that there was no further need for him to visit Bhagavan physically. Over the years, as I can testify, my father's features began to change, taking on something of the appearance of Bhagavan. Devotees and even strangers would look at him and then at the wonderful picture of Bhagavan at his side and exclaim on the likeness.

To the last he used to refer to Bhagavan as his father, and indeed, when I voluntarily took over the massaging of his legs I used to feel that Bhagavan was giving me an opportunity to serve him in that form.

On the day prior to his leaving the body, oxygen had to be administered. Suddenly my brother and I began to chant the holy refrain "Arunachala-Siva". We were supporting him in a sitting position. He opened his eyes and looked at the picture of Bhagavan in front of him. Tears began to trickle down his face. He indicated that we should lay him down. There was a beautiful smile on his lips. Soon after this he lost consciousness and throughout the night we chanted Bhagavan's "Marital Garland of Letters to Sri Arunachala". Incense was burning. A sweet and holy silence filled the entire house. Even the children, usually noisy, were very quiet. There was no movement in his body except breathing. At 5.30, on October 20th, 1961, the eastern horizon glowed red as though the Holy Arunachala were giving us darshan. There was a slight movement and it was over.

There was no weeping or outer show of grief. As it was puja season, the whole city through which we carried the body wore a festive appearance, with music, flowers, pandals and images of Mother Durga. Thus ended the story of the body. The spark of Bhagavan Ramana's eternal flame which had occupied Nilakanta's body merged into its Source in Bhagavan Ramana.Footnotes

1. This was the 'initiation by look'. Except when Bhagavan was in the sort of samadhi which is without outer consciousness or was concentrating in a Grace-giving-look like this, there was a constant slight shaking or trembling of his head. This was attributed to the power of the spiritual vibration in him.