The Sri Ramana Gita

Part V

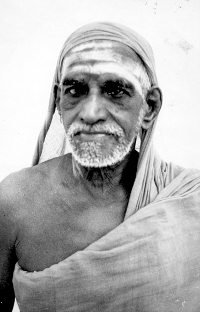

While B.V.Narasimha Swami was residing in Sri Ramanasramam, around the year 1930, he took up the project of recasting Ganapati Muni's Sri Ramana Gita in its original conversational form. For a full introduction to this recently-discovered manuscript see the July/August 2009 issue of 'The Maharshi newsletter.

In the present issue, we reproduce Chapter Six, along with its footnotes, titled "What is Manonasa (Mind-Destruction)?" In Sri Ramana Gita, published by Sri Ramanasramam, the same chapter is titled "Mind Control", corresponding to Ganapati Muni's Sanskrit title "Manonigropayaha". In BVN's version of this chapter the contents of verse five are mentioned, but are not so clearly defined as in Sri Ramana Gita. This verse, containing the simplest of breath control methods taught by the Maharshi, is universally applicable and appealing. The verse in Sri Ramana Gita is: "Control of breath means merely watching with the mind the flow of breath. Through such constant watching, kumbhaka does come about."

CHAPTER VI

What is Manonasa (Mind-Destruction)?

21-8-1927

Kavya Kantha: Bhagavan[1] has said that the re-entry of the mind into the heart as effected by the Jnani and known as the manonasa of Samadhi, is radically different from the disappearance of mind in disease, etc. The disciples desire to know something more of manonasa and manolaya, and how they are to be effected.

Maharshi then continued: Men find it hard to control their minds. That is the often-heard complaint. Do you see the reason? Day in, day out, almost every hour and every minute, they spend their time gratifying their numerous desires; and they are and have been wholly engrossed in their attachment to external objects, i.e., the non-Self. Hence, this outgoing tendency is deeply rooted and binds them like an iron chain. This strong vasana, instinct or tendency, has to be overcome before they can obtain the placidity, the equilibrium on which their realization has to be based. So let them begin at once, i.e., as early as possible, to reverse their conduct and to gain incessant mind control. Let them try to ride the mind and drive it to their goal, instead of allowing it to run away with them in any and every direction, driven by desires. They may start their endeavour with various helps.

The first help for mind control that is usually suggested to an aspirant is pranayama, breath-control or breath-regulation. The mind, like a monkey, is usually fickle, restless, fretful and unsteady. As you tie-up and restrain the monkey, or a bull, with a rope, so you may still the mind by regulating and holding the breath. When the breath is so restrained, the mind gets calm and its activities in the shape of thoughts cease. When there is no thought, the jiva's energy runs back into the source whence all its energies issue, i.e., into the center, the heart.

Next, proceeding to consider the methods of securing the retention of breath (kumbhaka), we note these various methods suggested or employed: The first and simplest course, the rajamarga, is simply to will the retention of the breath and rivet the attention on it. The breath then stops at once. At first, this riveting of attention and willing may involve strain and fatigue. But this must be overcome by incessant practice, till the willing and attending become habitual. Then the mind is quite relaxed when it thinks of kumbhaka; and you are at once holding the breath and the mind lies narcotised and stilled like a charmed serpent.

There are perhaps some who find that the above course does not suit them. Let them try, if they choose, another method, that of Hatha Yoga, which also achieves kumbhaka though with enormous strain and struggle. Ashtanga Yoga (i.e., Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi) is common to all the methods. The chief characteristics of Hatha Yoga are its adoption of bandhanas, mudras, and shatkarmas. Details as to the practice of Hatha Yoga are found in special treatises devoted to it, such as Hathayoga-Pradipika.

In both Raja Yoga and Hatha Yoga, you find rechaka, pooraka, and kumbhaka. By rechaka you expel the used-up air from the lungs through one nostril into the external air. Then you proceed to pooraka, i.e., to fill the lungs by drawing a deep breath of pure air from outside through the other nostril, and then follows the kumbhaka, the important process of holding within the pure air (in your chest) for a gradually increasing period. If the period of rechaka is taken as one unit, usually the period of pooraka is an equal unit, and that of kumbhaka is four units. This is said to promote the purity of the nadis, that is, the subtle nerves. These and the brain are perhaps rendered more efficient for Samadhi, i.e., for concentration or meditation on that which has no characteristics or attributes. The purified nadis (nerves) and the brain, in turn, help breath-retention or kumbhaka. Breath-retention is styled perfect or Suddha Kumbhaka, when breath is restrained in every way and completely.

Suddha Kumbhaka is also the name given to yet another method of pranayama. Here the abhyasi or aspirant attends only to the kumbhaka, leaving the periods of rechaka and pooraka without any special attention.

Of other methods, one only needs mention here. It is strictly speaking not a method of breath regulation but the figurative application of it. Those who adopt the pure Jnana or Vichara Marga disdain to attend to such a trifle as mere physical breath, and declare that rechaka consists in expulsion from within themselves of that useless or poisonous "dehatmabudhi" or "I am the body" idea. Pooraka (or the filling in, or drawing in of pure air into the system) consists, according to these, in the seeking and obtaining of light when they inquire into their the Self; and kumbhaka (i.e. the holding of pure air within and absorbing the same) consists, in their view, in the Sahaja Sthithi, i.e., the state of realising the Self as a result of the inquiry aforementioned.

Still others adopt the method of Mantra Japa, i.e., the incessant repetition of mantras (sacred sounds), to obtain manolaya [Manolaya is a temporary absorption of the mind in the object of meditation. Manonasa, destruction of mind, can alone give liberation.-Editor]. As they proceed incessantly with repetition of the sacred mantras with full faith and unflinching and unbroken attention, the breath (though unattended to) gets harmonised and in due course[2] is stilled in the rapt attention of the mind. The individuality of the mind is sunk in the form of the mantra. All these become one and there is Realization. The stage when prana (breath) is identified with or lost in the mantra is called dhyana (meditation), and Realization rests on the basis of dhyana that has become a firm habit.

Lastly, we may notice another method of getting manolaya. That is, association with great ones, the Yogarudhas, those who are themselves perfect adepts in samadhi, Self-realization, which has become easy, natural and perpetual with them. Those moving with them closely and in sympathetic contact gradually absorb the Samadhi habit from them.

1. In the Ashram, the disciples address Ramana Maharshi as Bhagavan and refer to him alone as "Bhagavan."

2. The due course of Japa was explained by Maharshi in his "Upadesa Sara" as proceeding from (1) the loudly uttered praise to (2) the faint but fervent whisper of His name, thence (3) to the utterance of the name in the heart which easily passes into deep and perpetual meditation or concentration, analogous to the flow of oil poured from one vessel into another, or the unceasing flow of water in a perennial river.

Sadhu Trivenigiri Swami

When I was in Tiruchendur in 1932 it came to my mind that I should regard all women as my mother or Valli, if I was intent on leading a spiritual life. One evening I went to the shrine of Sri Subramanya and stood for half an hour before the moolavar (main deity) and the following words flashed into my consciousness: "Here I am a god who does not talk. Go to Tiruvannamalai; Maharshi is a god who talks." This was how Maharshi's grace manifested itself to me. I had not even seen the Maharshi then.

In December 1932 I wrote to Ramanasramam and got the reply conveying Bhagavan's upadesa that the body is the result of prarabdha (accumulated karma) and the joys and sorrows relating to it are inevitable, and they can be borne easily if we put the burden on God.

One day in 1933, Vakil Sri Vaikuntam Venkatarama Iyer suddenly spoke to me about the Maharshi and gave me a copy of Ramana Vijayam in Tamiḷ. I read it and when I came to the part when Bhagavan's mother was crying before him to urge him to return home, I was choked with tears.

Then my mother made the following inspired utterance: "Malaiappan calls you, go to him. This path will result in the salvation of twenty seven generations of your family. This is the upadesa (teaching) of Mother Truth. Go along this path. Any obstacle you meet, regard as maya (illusion). You will soon be liberated." So saying, I was given upadesa of Mahavakyam and Karana Panchaksharam (Vedic truth of Brahman).

In February 1933, I wrote to the Ashram again and got a prompt reply. Bhagavan's upadesa given in it was as follows: "Sattvic food will keep the mind clear and help meditation. This is the experience of sadhakas. Eat to appease hunger and not to satisfy taste or craving; this will in due course lead to the control of the senses. Then continued and concentrated meditation will result in the annihilation of desires. It is the Atman that activates the mind and breath. Watching the breath will result in kevala kumbakam (stopping of breath). Control of breath will lead to temporary control of the mind and vice versa. Intense and constant japa (repetition of a sacred syllable) will lead to ajapa (non-repetition). Sound being subtler than form, japa is preferable to murti (image or form) or worship. Aham Brahmasmi (I am Brahman) is the best. To those who seek the source of the 'I', no other mantra or upasana (meditation) is needed."

I soon proceeded to Ramanasramam to stay there permanently. One day I decided to spend the nights for one mandala (cycle of 48 days) in the presence of Bhagavan. On the 15th day I had a dream: The attendant Madhavan had an epileptic attack and suddenly grasped my hand. I cried for help to Bhagavan who pulled away Madhavan's hand, and gave me milk to drink. When I woke up I still had the taste of the milk in my mouth; I felt I had drunk the milk of wisdom. From then onward my mind turned inwards.

Trivenigiri Swami

One morning while cutting vegetables, I wanted to do giri pradakshinam (circumambulation of the Hill) and asked Bhagavan's permission. Devotees nearby made signs pleading to Bhagavan not to let me go. Bhagavan said, "Is pradakshina a sankalpa (intention)? Let him go." I said, "No. I decided last night to go with somebody. That is all." Bhagavan, "Oh! You already made the sankalpa. Sankalpa leads to samsara. Fulfill the sankalpa. You need not cut vegetables." I took it as an upadesa (teaching) not to make sankalpas thereafter.

Another morning when I was cutting vegetables with Bhagavan, he said: "Sundaram! Take this hurricane light and pick up the mangoes that have fallen from the tree." I said "yes" but continued cutting up the vegetables. Bhagavan said, "Sundaram! Attend to what 'I' said first. It is from me that everything rises. Attend to it first." I took this as an adesh and upadesa (advice and instruction) to make the enquiry "Who am I?" My friends also felt so.

One day the attendant Madhavan was binding a book. A devotee wanted a book from the library. Bhagavan asked Madhavan to get it saying, "You do my work; I will do your work." And Bhagavan took the book and went on with the binding while Madhavan got the library book. A devotee interpreted this as follows: "My work means looking after the needs which arise in the minds of devotees for anything from Bhagavan. Your work is to get liberation which is not possible without Bhagavan's Grace and help." Bhagavan heard this comment and said "Hum Hum! That is what it is!"

Once when meditating in the presence of Bhagavan, the mind persisted in wandering. I couldn't control it. So I gave up meditation and opened my eyes. Bhagavan at once sat up and said, "Oh! You abandon it thinking it is the swabhava (nature) of the mind to wander. Whatever we practise becomes the swabhava. If control is practised persistently that will become the swabhava." Yet another upadesa for me.

God Alone Exists

THOSE who have realized the Self remain uninvolved, even when they are engaged in everyday activities. They are always in a state of utter stillness. Bhagavan himself has described this in the thirtieth verse of the Supplement to Reality in Forty Verses:

"The mind that is devoid of attachments, though it may appear to be engaged in activity, is in reality inactive - just as the mind of a person listening to a story might wander off to a faraway place."

Once, in the Jubilee Hall, we were all listening to the radio. At the end of the program the names of all the artists were announced. Bhagavan said, "See! The radio sings and gives speeches. It even announces the names of the performers. But there is nobody inside the radio. Our existence is also like that. The body might appear to walk and talk and perform a number of functions, but in fact there is no individual inside the body. Everything is God. He alone exists." Bhagavan continued, "The concepts of time and space are also imaginary. When we listen to a concert on the radio are we bothered about the exact time and location at which the concert took place? What difference can it make to our enjoyment of the music?

Whether the concert took place in Hyderabad or in Madras, we can listen to the music and derive the same degree of enjoyment sitting right here in this hall.

The wise one does not attach any importance to concepts of space and time. One has to go through certain situations in a given lifetime and for this a body is required. That is the only reason for acquiring a body. One goes through various experiences without getting involved in anything. To an ordinary person, worldly experiences seem real. An ordinary man might think that a liberated person has all the experiences that others have. But the liberated person has no attachment to the body and therefore physical experiences hold no significance for him.

The jivanmukta has the same attitude towards his body that a railway porter has for the luggage he carries. Just as the porter carries the luggage up to the destination and lays it down at that spot, the jivanmukta carries the body through the pre-ordained experiences of a lifetime and at the end of the course he lays down the burden with relief. The porter thinks of the load on his head only as a burden; he does not identify with it on a personal level. That is why he feels no regret when he puts it down. It is the same in the case of a jivanmukta. As he never thinks of the body as having any personal significance, he feels no sorrow when the time comes for him to leave the body."

During the last days of Bhagavan's earthly life, when his devotees besought him to retain the human form for a long time, Bhagavan used to say, "A jnani (a realised soul) knows that the sole purpose of acquiring a body is to enable the spirit to attain knowledge through experiences. Do we feel sad because we have to throw away the used leaf-plate after a meal? In the same way, a jnani discards the human body without any regret or sorrow."

A Talk with Ramana Maharshi

In as much as India is notoriously the most metaphysically minded of all countries, it was natural that I should seek discussions in this field.

Ever since I had read Paul Brunton's 'A Search in Secret India', I had been keen to visit Ramana Maharshi, the sage whom Brunton found most impressive of all those he sought out. Soon after my arrival at his Ashram, I bade one of the two men who mainly ministered to him to inquire whether I might ask of him two questions. Accordingly, I was requested to take my seat in front of the group of visitors and an interpreter sat next to me (although the Maharshi usually gets queries directly through English) and was invited to present my question.

The first of these questions was: "If it is true that all the objective world owes its existence to the ego, then how can that ego ever have the experience of surprise as it does, for example, when we stub our toe on an unseen obstacle?"

Sri Bhagavan answered, "The ego is not to be thought of as antecedent to the world of phenomena, but rather that both rise or fall together. Neither is more real than the other. Only the non- empirical Self is more real. By reflecting on the true nature of the Self, one comes at length to undermine the ego. At the same time one realizes that the material obstacle and the stubbed toe are equally unreal, and one learns to dwell in the true Reality which is beyond them all."

He then went on to outline that we only know the object at all through the sensations derived from it remotely. Moreover, physicists have now shown that in place of what we thought to be a solid object there are only dancing electrons and protons.

I replied that while we have, indeed, direct knowledge only of sensations, we know less, for all that knowledge, about the objects which give rise to the sensations, about which knowledge is checked continually by making predictions, acting on them and seeing them verified or disproved. Furthermore (here I went on to my second query), "If the outer phenomena which I think I perceive have no reality apart from my ego, how is it that someone else also perceives them? For example, not only do I lift my foot higher to avoid tripping over that stool yonder, but you also raise your foot higher to avoid tripping over it too. Is it by a mere coincidence that each of us independently has come to the conclusion that a stool is there?"

Sri Maharshi replied that the stool and our two egos were created by one another mutually. While one is asleep, one may dream of a stool and of persons who avoided tripping over it just as persons in waking life did, yet does that prove that the dream stool is any more real? And so we had it back and forth for an hour, with the gathering very amused, for all Hindus seem to enjoy a metaphysical contest.

During that afternoon's darshan I again had the privilege of an hour's talk with the Maharshi himself. Observing that he had given orders to place a dish of food for his peacock, I asked, "When I return to America would it be good to busy myself with disseminating your books to the people just as you offer this food to the peacocks?" He laughed and answered that if I thought it good it would be good, but otherwise not. I asked whether, quite apart from whatever I thought, wouldn't it be useful to have pointed out a way to those who were ripe for a new outlook? He countered with, "Who thinks they are ready?"

The Maharshi went on to say that the essential thing is to divorce our sense of self from what our ego and our body are feeling or doing. We should think 'feelings are going on, this body is acting in such and such a manner,' but never 'I feel, I act.' What the body craves or does is not our affair.

I then asked, "Have we then no responsibility at all for the behaviour of our ego?"

He replied, "None at all. Let it go its own way like an automaton."

"But", I objected, "you have told us that all the animal propensities are attributes of the ego. If when a man attains jivanmukti he ceases to feel responsibility for the behaviour of his ego and body, won't he run amok completely?" I illustrated my point with the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Maharshi replied, "When you have attained jivanmukti, you will know the answer to those questions. Your task now is not to worry about them but to know the Self."

But I am forced to doubt the whole theory unless it explains away this discrepancy: "Here before us is the Maharshi who has attained jivanmukti and so withdrawn from all responsibility for the conduct of his ego and the body we see before us. But though he declares them to be the seat of all evil propensities, his ego and body continue to behave quite decorously instead of running wild. This forces me to suspect that something in the hypothesis is incorrect."

He answered, "Let the Maharshi deal with that problem if it arises and let Mr. Hopkins deal with who is Mr. Hopkins."

Dr. Pryns Hopkins (1885-1970) was a resident of Santa Barbara, California, a scholar of psychology, an enthusaistic follower of Freud, a world traveler, philanthropist, founder of two progressive schools and author of many books. He inherited wealth and spent it generously on social programs and organizations. During his travels he met with the great thinkers and political kingpins of his day, including Winston Churchill, Hitler and Freud. He was the son of distinguished parents, whose history traces back to the founding fathers of the nation.

Letters and Comments

Practice of Self-Enquiry

For about twelve years I have been trying to practice, off and on, Self-enquiry. For example, in each year for about fifteen days I take to some form of practice, and the 350-day balance there is the same mundane existence, i.e, without any practice.

For about ten years, when any thought would come, I would say to myself 'To whom is this thought?' 'To me' I would answer, and then I would ask 'Who am I?' and thus eliminate that thought. I was not always successful, though.

In the last one to two years, I am also trying David Godman's interpretation of Bhagavan's teachings by holding onto the 'I-thought' and occasionally trying to hold my breath and dive within myself to seek the source of the 'I-thought'. Using these two methods, occasionally I felt that I was making some progress, albeit less with the former method.

Kindly advise me as to what can be my future sadhana and also your feedback on the above three methods .

First of all, if you are to walk on the path of realization by seeking the Source of your being, you cannot get very far on it by half-hearted attempts. There are no shortcuts. It requires complete dedication to the ideal and strenuous, lifelong effort in pursuit of it. Unless you come to understand that the purpose and goal of life is to realize the Self, you cannot, in truth, make any meaningful progress, or expect to make much progress. Bhagavan has said that those few who have succeeded owe their success to perseverance. That means day in and day out effort, unrelenting.

So whatever method you take up, you have to do it sincerely and steadily, for a whole lifetime if need be. The path to realization is a vocation in life, not just something we take up at intervals. We eat everyday, we breathe constantly. Spiritual pursuit must be as vital and natural to you as these.

Once we are clear about this point and attempt to realize the Truth with all our heart, God comes forward and guides us, makes the situations in our life conducive to spiritual progress. But we cannot judge this progress easily. No effort ever goes in vain. And if we strive relentlessly, His grace will take hold of us and carry us to the goal. This is what all true sadhakas have to do to attain realization.

If you are unable to commit yourself to this ideal, then pray to God, or Bhagavan, to bless and inspire you with sincere determination. That is all that is within your power. Surrender to Him wholeheartedly and await His grace. Also, think about the ephemeral nature of all things in life, your experiences, your joys and sorrows — how you are always seeking to grasp a bit of happiness from pursuing and fulfilling desires, but only experience short-lived pleasures in the end, followed by more desires and pursuits. This is an endless cycle that replays itself, life after life, birth after birth. Be clear about this, reflect on the underlying Reality and seek it. No one can do this for you. Start now with a determined, unrelenting effort. That is the only way.

Being Still

I first became involved in non-duality about six years ago. Over the past three or four years, I've practiced 'Being Still.' 'Being Still' is, for me, meditating in a thought-free state. For me, that state occurs similar to turning a switch on or off, but it takes effort to keep it going. And running a business really interferes with it. Yet, before a sudden experience during meditation a couple of years ago showed me how to 'switch it off,' nearly my whole life had been spent neck deep in thoughts, and I was amazed to finally see the ensnarement.

In turn, if I stir at night, I occasionally wake immersed in Consciousness. This happened a month ago when I woke for a short while unaware of my body or the world or an 'I', but existing completely as Consciousness-Bliss that I assume is what is referred to as the 'Natural State.' This has not happened in the daytime through 'Being Still,' but I'll just surrender this and let it develop as it does. Also, hearing from friends who have gone to Sri Ramanasramam, India, I would very much like to travel to India and sit for many days in the Old Hall at the Ashram. When finances and personal responsibilities allow it, I really hope to go visit the Ashram and walk the path around Arunachala.

Please place me on your mailing list, and stay in touch.

— American devoteeWe read with interest your letter and have been waiting for an opportunity to write to you about it.

Bhagavan has mentioned about the mostly-unnoticed state, when transitioning from sleep to waking. During that transition there is a brief moment of pure awareness. Those who have experienced that awareness just prior to waking can sometimes take hold of it. And the fact that you have experienced it shows that you have two factors that will benefit your spiritual aspirations.

First, you have a natural predilection, or purva samskara, to seek the Ultimate Truth. You came into this world with it and you most certainly had pursued it in the past. Secondly, Bhagavan's grace is working in you, guiding you, revealing the truth of his teachings and showing you the path to liberation. This is certain.

You mentioned that "...running a business really interferes with it." By 'it' you of course mean the pure-awareness experience. Bhagavan teaches that to believe that work and family obligations obstruct our spiritual experience is a myth.

These outward activities go on propelled by our prarabdha karma. Identifying with - or projecting our ego into - them, binds us and obstructs the realization of spiritual truths. If we cease to identify with the actions, doing what appears to be right spontaneously, without thought of gain or loss and not allowing any residue of attachment to the action to stick, those activities will be a source of freedom. By deep and steady meditation and the performance of actions in the above manner, your identification with the ego will slowly dissolve. One day you will awake and say, 'Where is that rascal? He is nowhere to be found. How is it that I identified with him for so long?'

This is the process and we can always move forward, deepening our experience by sincere effort and the grace of the Master.

Sri Ramana's Children's Ashrama Summer Camp

July 19th-23rd, 2010

(Monday - Friday)This year's intergenerational children's camp will be rich with stories of Bhagavan Ramana and devotional music. There will be simple meditation instruction for kids with focus on the development of a prayerful attitude. Special outdoor activities will include hiking and canoeing. Of course, a Bhagavan Ramana play production will top off the week followed by a corn roast, singing by the bonfire campers' awards for one and all!.

For information please contact the Ashrama or call Darlene in Nova Scotia at 902-665-2263.

Arunachala Ashrama

1451 Clarence Road

Bridgetown, Nova Scotia

Canada B0S 1C0

902 tel.#