Conversations with Swami Viswanathan

Part 1

This transcribed conversation between Arunachala Bhakta Bhagawat and Swami Viswanathan which was recorded while on a giripadakshina in August of 1973.

B: Bhagavan’s teaching is so direct and yet so simple.

S: Bhagavan has emphasized that it is the natural state of our being. Somehow we have forgotten it – our own reality – and we have to remember it by vichara (enquiry), by devotion.

One gets that experience of samadhi after many years, after a whole life of sadhana. So, I am translating that part of Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi in which Bhagavan says, “You are always in samadhi.” Even when we are interested in doing work, we are only in samadhi. By samadhi I mean the Self. Samadhi and the experience of the Self are not different. It is there as the background. Whether we know it or not, whether we recognize it or not, it is there.

B: Yes, they say that it takes a lifetime of practice to experience samadhi.

S: What are known as vasanas is the inclination of the mind towards objects. The extroverted mind is so strong that it takes a long time to correct it and bring it back into the heart. This is not the achievement of anything new, but the stilling of the mind by practice....by japa, by bhakti, by nama sankirtanam, or by meditation or vichara: the object is to still the mind. Bhagavan has quoted this from the Bible also: “Be still, and know that I am God.”

One of the works that Bhagavan has translated is the “Devikalottaram”. It says: ‘tadeva janma sāphalyam’. That is the achievement of life’s tapas (janma sāphalyam) and that is true learning (pāndityam idameva hi. caladvāyusamam cittam nishcalam ghriyatehi yat). It is the art of making the mind still. The mind is always wavering. Difficult it is to make it still. That is the greatest thing of all, and that is the achievement of a life of tapas. Because when the mind is made still, one gets in tune with the infinite Self within. There is nothing beyond it. [1]

He (Bhagavan) would say to the devotees, don’t worry that by your herculean efforts you are going to get something in the distant future. It is already achieved. It is there with you. Only on account of the fickleness of the mind it is not experienced. So, by some method or other that appeals to you, try to make your mind still without worrying about it, because it is already achieved, it is not new.

He is the true guru who at once removes the anxiety of the devotee that comes to him. He does not advise a long course of sadhana that after so many years you will achieve something. Immediately as soon as one goes to him, one experiences the great calmness of Bhagavan. It is so powerful that everyone automatically has to be still in this presence. And anyone who visits Bhagavan feels like coming again and again to him. That’s what Paul Brunton also wrote in his first book (A Search in Secret India). Brunton was puzzled when Bhagavan did not turn towards him at all. He asked him to sit, then he remained as usual – looking at nothing, looking at the window at the other end. “He didn’t seem to be conscious of my existence of even (being) there...Then after a few minutes, as my mind began to get calmer and calmer, I felt as if a steady river of peace was flowing near me...the fragrance of a forest flower was being wafted...then my thought-tortured brain found real rest for the first time in my life,” wrote Brunton.

S. [Commenting while walking] This place is called Durvāsa Ashrama. This Rishi is reputed to be the angry sage who cursed Sakuntala, in the drama of Kalidasa. She was lost in the thought of the husband who had forgotten her. This muni passed that way and he felt that she did not notice his presence or give him due respect, and then cursed her.

All the individual sages have got their own individual traits. They are beyond the gunas, the three gunas, yet they have got their own peculiarities. Their anger only purifies. I have seen Bhagavan in anger sometimes (Swami laughs). The moment he gets angry there would be an alarm sent out everywhere. Everybody would be on the alert. But the next moment Bhagavan would be laughing (everyone laughs). It was all feigned.

Also, this sage Durvāsa is reputed to be a great devotee of the Mother. So, I wrote a verse on him. It is called “Krodha Bhaktāra”. Bhaktāra means ‘jnanam’. It is applicable to great kings as well as great sages. I found an image of this sage when I went to Kanchipuram, the (abode) of the Mother Kamakshi, and I felt like writing a verse on him. I wrote like this:

sri matre charanām bhavaja vilāsa ullāsa harshitam, krodhabhaktārakam vande bhagavantam taponiddhim.

He is reputed as the angry sage but he is so immersed in the bliss of the Mother that he would not injure (anyone).

Sri matre charanām bhavaja vilāsa ullāsa harshitam. The play of the Mother is happy; taking part in it is blissful. And he is taponiddhi (a treasure of austerity), Bhagavan. He is known as krodha bhaktāra.

B. What was the experience of people approaching Bhagavan’s presence?

S. It is but natural for anybody approaching it, when there is some powerful influence, to be affected by it, to be influenced by it – it is but natural and simple. Bhagavan was the Self incarnate and full of that experience. He was the Spirit, the Atman. He outwardly appeared as an individual, but he was the Universal Self. That experience was so powerful in him that anybody who has sat near him was enabled to get it (the experience). Just as you feel light and heat in the presence of the sun, in the same way there was the experience. Look how natural it is that his experience, his mere presence is a blessing for the whole universe.

That’s what Vinoba Bhave wrote when Bhagavan passed away. He got the news on his walking tour. He said that just now I have gotten the information that Ramana Maharshi has obtained brahmanirvana. “He did not give up the body now, but did that long, long ago when he realized the Self in his seventeenth year and discarded the body. Since there was no difference for him between life and death (of the body), he gave up the body.” And while thinking of Bhagavan he continued walking. People nearby asked him, “What good did Ramana Maharshi do to the world?”

“It was only he who helped the whole world. He was not confined to his own petty interests, but his interest was universal. What good did he do for the world? What am I to say to you?”

Ramana Maharshi’s experience was such an exalted one that he had not to do anything with his mind or senses or his body. His mere presence was bliss. Just as the sun’s presence gives us light and heat.

[ 1 ]

tadeva janma sālphlyaṁ pāndityamidamevahi |

caladvāyusaṁ cittaṁ niścalaṁghriyatehiyat ||

“When one adopts the practice (sadhana) by means of which one’s mind,

which is restless like the wind, is made still perpetually,

then the purpose of taking birth as a human being is fulfilled.

That is also the mark of a true scholar.”

Sadhu Arunachala (Major A.W.Chadwick)

Louis Buss from England has been inspired to do extensive research and writing on the life of Alan Wentworth Chadwick, his family members and the historical influences that guided the course of their lives. In Louis’ manuscript Chadwick’s life’s journey is also neatly woven together with the life and teachings of the Sage of Arunachala, Sri Ramana Maharshi. Below is a short excerpt from Chapter 36, “Marooned”.

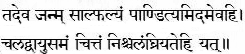

The Meditation Belt

But the most glorious symbol of Chadwick’s captivity here was his famous meditation belt. Once he’d realised that the natives found the sight of him sitting on a chair in the Old Hall singularly offensive, the most pressing problem this spiritual Crusoe faced was making himself comfortable at his guru’s feet. After all, that was the only reason he was on this desert isle in the first place. He was undergoing all this isolation and difficulty just so that he could sit in the presence of Bhagavan. In the absence of chairs, the whole enterprise became pointless if he couldn’t sit on the floor.

The answer was a strip of canvas some six or eight inches across whose two ends could be fastened together with a pair of large catches. Like most of us who can’t sit cross-legged, Chadwick generally attempted to make himself comfortable in that position by clutching his knees. This, of course, provided only the most precarious and temporary of solutions, which might just about be sustained for the time required to take a photograph, but was not really conducive to long meditation sessions. The canvas belt solved the problem by clutching Chadwick’s legs for him, thus leaving him free to relax his arms. Once he had wrapped the belt around his back and fastened it in front of his legs, all he had to do was rest against a wall, and he would be able to sit there quite happily for hours.

Comfortable though it may have been, the belt did look rather odd. The tall Westerner in his white pajamas was already conspicuous enough in the Old Hall, but that contraption made him little short of freakish. One day as everyone was getting up to go for lunch, Bhagavan caught Chadwick’s eye. Realising that he wanted to say something, Chadwick approached the couch. It appeared that some schoolboys, noticing his predicament, had gone up to Bhagavan and said in Tamiḷ:

‘What has he done wrong? Why have you tied him up like that?’

If Bhagavan found this so hilarious, it was perhaps partly because he understood the symbolism of that belt. Like all of us, Chadwick could only become liberated by allowing himself to be tied up. Only imprisonment could set him free. The ultimate victory can be won only by surrender, just as only death can secure immortality. And in a way, the schoolboys were absolutely right: it really was Ramana Maharshi who had tied Chadwick up in that belt and kept him marooned here. His freedom to leave whenever he chose was purely theoretical. In practice, his predicament was worse than Robinson Crusoe’s had ever been. At least Crusoe had awoken each day to the hope that a ship might appear to take him home. No ship could ever come for Chadwick, for this was a magic isle, where the chains of enchantment were forged by the castaway himself. The most hopeless prisoner of all is the one who conspires in his own captivity. A determined convict can file away the bars, loosen the bricks of the cell or dig a tunnel with a teaspoon. As long as the will to escape remains, anything is possible. But from the moment Chadwick set eyes on Ramana Maharshi, he was lost.

That meditation belt was the perfect symbol of the magic circle in which he found himself trapped. Although he appeared to wrap himself up in it and fasten the catches with is own hands, his actions were no longer his own. Those schoolboys were closer to the truth than they could have known, for Bhagavan had not tied Chadwick up only in a symbolic sense. It later turned out that Ramana had made that restraining belt with his own hands, given it to Chadwick as a gift, and then sworn him to secrecy. The adoration he inspired meant that Ramana had to be very careful. If he wrote a line for someone in a book, he would find himself besieged by requests to do the same thing again, and the Old Hall would soon have resembled a bookshop where a famous author was signing copies. If Ramana had taken it into his head to go on an expedition somewhere, the entire ashram would have trooped behind him. In short, nobody was more hopelessly marooned on this little island than Prospero (Bhagavan) himself.

That was why he swore Chadwick to secrecy when he presented him with his belt. If news of this got out, everyone would want one, and before you knew it the ashram bookstall would be marketing the famous Ramana Maharshi Meditation Belt. It is a measure of how solemnly Chadwick treated his Master ’s commands that he kept this secret for so many years. Even when he came to write his Reminiscences, he didn’t let anything slip. But eventually, in a conversation with Sri Ganesan, he revealed who had really made the belt.

‘Why didn’t you put that in your book?’ said Ganesan. ‘You could at least have given us a clue!’

‘But I did give you a clue!’ said Chadwick. ‘Read it again!’

So here is what A Sadhu’s Reminiscences has to say on the subject of the famous belt:

‘I had then, and still have, considerable difficulty in sitting on the floor for any length of time in spite of years of practice. Afterwards I devised a meditation belt of cotton cloth which I brought round from the back across my raised knees and with this support could sit comfortably for long periods. Such belts are regularly used by Yogis, though strange as it may seem I had no idea of this when I devised my own. Bhagavan told me that his father had had one but had not used it in public.’

If this is Chadwick’s idea of a clue, it makes one wonder how many other secrets his Reminiscences may hold. You could certainly read the book any number of times without beginning for a moment to suspect what had actually happened. But it seems that as a boy Ramana had noticed his father using such a belt. Years later, realising Chadwick’s determination to sit in his presence and the difficulties he had in doing so, he had recreated the belt and presented it to him. Chadwick’s secrecy about this after so many years does seem rather excessive. Perhaps he kept quiet not so much out of a lingering reluctance to break a promise to Bhagavan, no matter how redundant it had become, as from a reluctance to blow his own trumpet. For the meditation belt was yet more evidence of the special care and attention lavished on this particular castaway by the Enchanter of the Isle.

It was also the nearest Ramana could come to blowing his own trumpet, an implicit confirmation that his own silent presence was the ultimate meditation aid. In his presence, people made extraordinarily rapid progress. All they had to do was sit there. When asked how best to make use of this opportunity, the Maharshi replied:

Keep your mind still. That is enough. You will get spiritual help sitting in this hall if you keep yourself still. The aim of all practices is to give up all practices. When the mind becomes still, the power of the Self will be experienced. The waves of the Self are pervading everywhere. If the mind is in peace, one begins to experience them.

Settling into the Ashram

The ensuing weeks absorb me into a strange, unwonted life. My days are spent in the hall of the Maharshi, where I slowly pick up the unrelated fragments of his wisdom and the faint clues to the answer I seek; my nights continue as heretofore in torturing sleeplessness, with my body stretched out on a blanket laid on the hard earthen floor of a hastily-built hut.

This humble abode stands about three hundred feet away from the hermitage. Its thick walls are composed of thinly-plastered earth, but the roof is solidly tiled to withstand the monsoon rains. The ground around it is virgin bush, somewhat thickly overgrown, being in fact the fringe of the jungle which stretches away to the west. The rugged landscape reveals Nature in all her own wild uncultivated grandeur. Cactus hedges are scattered numerously and irregularly around, the spines of these prickly plants looking like coarse needles. Beyond them the jungle drops a curtain of scrub bush and stunted trees upon the land. To the north rises the gaunt figure of the mountain, a mass of metallic-tinted rocks and brown soil. To the south lies a long pool, whose placid water has attracted me to the spot, and whose banks are bordered with clumps of trees holding families of grey and brown monkeys.

Each day is a duplicate of the one before. I rise early in the morning and watch the jungle dawn turn from grey to green and then to gold. Next comes a plunge into the water and a swift swim up and down the pool, making as much noise as I possibly can so as to scare away lurking snakes. Then, dressing, shaving, and the only luxury I can secure in this place three cups of deliciously refreshing tea.

“Master, the pot of tea-water is ready,” says Rajoo, my hired boy. From an initial total ignorance of the English language, he has acquired that much, and more, under my occasional tuition. As a servant he is a gem, for he will scour up and down the little township with optimistic determination in quest of the strange articles and foods for which his Western employer speculatively sends him, or he will hover outside the Maharshi’s hall in discreet silence during meditation hours, should he happen to come along for orders at such times. But as a cook he is unable to comprehend Western taste, which seems a queer distorted thing to him. After a few painful experiments, I myself take charge of the more serious culinary arrangements, reducing my labour by reducing my solid meals to a single one each day. Tea, taken thrice daily, becomes both my solitary earthly joy and the mainstay of my energy. Rajoo stands in the sunshine and watches with wonderment my addiction to the glorious brown brew. His body shines in the hard yellow light like polished ebony, for he is a true son of the black Dravidians, the primal inhabitants of India.

After breakfast comes my quiet lazy stroll to the hermitage, a halt for a couple of minutes beside the sweet rose bushes in the compound garden, which is fenced in by bamboo posts, or a rest under the drooping fronds of palm trees whose heads are heavy with coconuts. It is a beautiful experience to wander around the hermitage garden before the sun has waxed in power and to see and smell the variegated flowers.

And then I enter the hall, bow before the Maharshi and quietly sit down, folded legs. I may read or write for a while, or engage in conversation with one or two of the other men, or tackle the Maharshi on some point, or plunge into meditation for an hour along the lines which the Sage has indicated, although evening usually constitutes the time specially assigned to meditation in the hall. But whatever I am doing I never fail to become gradually aware of the mysterious atmosphere of the place, of the benign radiations which steadily percolate into my brain. I enjoy an ineffable tranquillity merely by sitting for a while in the neighbourhood of the Maharshi. By careful observation and frequent analysis I arrive in time at the complete certitude that reciprocal inter-influence arises whenever our presences neighbour each other. The thing is most subtle. But it is quite unmistakable.

At eleven I return to the hut for the midday meal and a rest and then go back to the hall to repeat my programme of the morning. I vary my meditations and conversations sometimes by roaming the countryside or descending on the little township to make further explorations of the colossal temple.

From time to time the Maharshi unexpectedly visits me at the hut after finishing his own lunch. I seize the opportunity to plague him with further questions, which he patiently answers in terse epigrammatic phrases, clipped so short as rarely to constitute complete sentences. But once, when I propound some fresh problem, he makes no answer. Instead, he gazes out towards the jungle-covered hills which stretch to the horizon and remains motionless. Many minutes pass but still his eyes are fixed, his presence remote. I am quite unable to discern whether his attention is being given to some invisible psychic being in the distance or whether it is being turned on some inward preoccupation. At first I wonder whether he has heard me, but in the tense silence which ensues, and which I feel unable or unwilling to break, a force greater than my rationalistic mind commences to awe me until it ends by overwhelming me.

The realization forces itself through my wonderment that all my questions are moves in an endless game, the play of thoughts which possess no limit to their extent; that somewhere within me there is a well of certitude which can provide me all the waters of truth I require; and that it will be better to cease my questioning and attempt to realize the tremendous potencies of my own spiritual nature. So I remain silent and wait.

For almost half-an-hour the Maharshi’s eyes continue to stare straight in front of him in a fixed, unmoving gaze. He appears to have forgotten me, but I am perfectly aware that the sublime realization which has suddenly fallen upon me is nothing else than a spreading ripple of telepathic radiation from this mysterious and imperturbable man.

On another visit he finds me in pessimistic mood. He tells me of the glorious goal which waits for the man who takes to the way he has shown.

“But, Maharshi, this path is full of difficulties and I am so conscious of my own weakness,” I plead.

“That is the surest way to handicap oneself,” he answers unmoved, “this burdening of one’s mind with the fear of failure and the thought of one’s failings.”

“Yet if it is true ?” I persist.

“It is not true. The greatest error of a man is to think that he is weak by nature, evil by nature. Every man is divine and strong in his real nature. What are weak and evil are his habits, his desires and thoughts, but not himself.”

His words come as an invigorating tonic. They refresh and inspire me. From another man’s lips, from some lesser and feebler soul, I would refuse to accept them at such worth and would persist in refuting them. But an inward monitor assures me that the Sage speaks out of the depth of a great and authentic spiritual experience, and not as some theorising philosopher mounted on the thin stilts of speculation.

Another time, when we are discussing the West, I make the retort:

“It is easy for you to attain and keep spiritual serenity in this jungle retreat, where there is nothing to disturb or distract you.”

“When the goal is reached, when you know the Knower, there is no difference between living in a house in London and living in the solitude of a jungle,” comes the calm rejoinder.

And once, I criticise the Indians for their neglect of material development. To my surprise the Maharshi frankly admits the accusation.

“It is true. We are a backward race. But we are a people with few wants. Our society needs improving, but we are contented with much fewer things than your people. So to be backward is not to mean that we are less happy.”

How has the Maharshi arrived at the strange power and stranger outlook which he possesses? Bit by bit, from his own reluctant lips and from those of his disciples, I piece together a fragmentary pattern of his life story.

Calling Ramana

ON ONE occasion, probably in 1939, Sri P.M.N.Swamy, a staunch devotee of Bhagavan and Secretary of Sri Ramana Satchidananda Mandali, Matunga, went to the Ashram at Tiruvannamalai to have darsan of Bhagavan and stayed for the day with his wife and nine-month old child, Ramanan. They had their breakfast in the common dining hall in the morning after finishing which they went to wash their hands at the tap outside, leaving the child in the hall itself. By the time Sri Swamy and his wife returned to the hall, the child Ramana had crawled away somewhere and could not be seen in the hall. The perturbed father called out to the child as ‘Ramana, Ramana’. Bhagavan, who was then passing on his way to the Meditation Hall, immediately responded to the call and the child also was found near the well in the Ashram compound. The response from Bhagavan naturally created a puzzle in Sri P.M.N.Swamy’s mind because he thought that the call ‘Ramana, Ramana’ intended for his child might have been wrongly interpreted by Bhagavan. But Bhagavan was quick to read Sri Swamy’s mind and told him “Why did you feel puzzled when I responded to the call? Is there any difference between this Ramana (meaning himself) and that Ramana (meaning the child)?”