How I Met The Maharshi

I met Arthur Osborne in an internment camp in Bangkok during the Second World War. At first I had little contact with him because he was very reserved. After some time, however, I approached him. I had a craving to understand and asked him point blank what is Truth. What sticks in my memory is how, sitting beside his bed in the common dormitory, he said. “I will tell you one truth – Infinity minus X is a contradiction in terms because by the exclusion of X the first term ceases to be infinite. You grant that?” Yes, I granted that.

“Well, then,” he said, “think of God as Infinity and yourself as X and try to work it out.” When I asked for more explanation he just said: “Think this over and come tomorrow at this time and tell me what you make of it.”

I returned to my place in the dormitory, which was only some eight or ten steps distant, and suddenly it flashed upon me that he was right, that you cannot take anything away from the Infinite, and that I was not apart from it, only I had not known.

The thought made me so happy that I could hardly wait to speak to him the next day, but I did not like to disturb him earlier.

From that time onward he started to instruct me and after a few weeks he showed me a photograph of the Maharshi. There was an urgency in his voice as he spoke of him and he handled the photograph with reverence. I began to understand that there was only one ‘I’ and that it was in me and was everywhere.

The Maharshi grew so much in my heart that I felt him nearer to me than my parents or my wife. He lived more vividly in me than any person I had known. After some time we received permission to write a Red Cross letter to our families and I used mine to write to the Maharshi and ask him for guidance.

Then the war ended and I left the camp. The desire to enjoy life sprang up in me again.

I was strongly drawn to the spiritual path but even more strongly, for the time being, to a worldly life. I wanted to make money, to have power and fine clothes, to be important. In camp I had eliminated day-dreaming as far as possible. When I went to bed at night I slept straight away. But now my nights were often filled with planning and scheming.

A few years later when I was in Europe and due to return to Siam on business, I wrote to Osborne, who was living at Tiruvannamalai, to suggest that I should break my journey in India and stay there for a few days. He at once wrote back arranging to meet me and conduct me there and invited me to stay at his house.

In Madras we hired a car and drove to Tiruvannamalai. It was an old car and I felt that I was being slowly roasted in the midday heat. When I let my eyes rest on the sunbaked scenery or the country folk sheltering under the wayside trees I saw only the face of the Maharshi looming up before me. Nothing else registered.

I was terribly scared that the Maharshi would look in my eyes and see into me. I cursed myself for a fool for coming to this desolate place, with its heat and discomfort. I don’t know what prevented me from turning back; perhaps I was afraid to show Osborne what a coward I was. The nearer we approached the Ashram the more I shrank from meeting the Maharshi.

It was nearly dusk when we arrived and he had already retired, but Osborne went in to see him and asked whether he would see me for a few moments. I entered the hall and saw an elderly man reclining on a couch, who gave the impression of great reserve and certain shyness. It was not the severe Master or the Guru with the burning eyes that I had expected. Osborne explained who I was, and his replies were monosyllabic and sometimes in Tamiḷ. With a slow movement of the head he turned to me and held my eyes for a moment. His eyes were like empty, bottomless pools and at the same time they worked like magic mirrors, because suddenly I felt at peace, as though I had come home after a long journey.

I can’t recall where I slept that night, but I do remember that before going to bed I sat and talked with a number of people, Indians and foreigners, at Osborne’s place. One of them was a diplomat from some European country, stationed in China. He talked about seeing spirits and even conversing with them, and it struck me as funny that anyone should be interested in such things at a place like this.

Sitting in the hall the next day I saw that the Maharshi’s smile was tender and gracious. I not only lost my fears but felt at ease. I had no questions to ask. Before coming I had prepared a number of questions that had been worrying me to ask the Maharshi, but now I couldn’t remember them. My doubts had simply evaporated. Questions seemed unimportant.

I felt that there was nothing strange about the Maharshi. He was just a man who was himself, whereas all of us were growing away from ourselves. He was natural; it was we who were not. We call him a saint or sage, but I felt that to be like him is the inheritance of everybody; only we throw it away.

There were a lot of people in the hall – Indians and foreigners, learned professors and simple country people. I reminded the Maharshi about the Red Cross letter I had sent him and he replied that he wanted me to come and I had come. There was something childlike about him: he was free and natural and could laugh with the spontaneity that only a child shows.

A discussion started in the hall and they appealed to the Maharshi to say who was right. Someone spoke about unity and I objected that the word implied two to be united and that a better word was Oneness; and the Maharshi confirmed this. He said that there is only One, and that One is indivisible. I felt that he meant that the divisions are all unreal, just as we say rain, ice, water, coffee, washing water, but it is all water.

A group of devotees started singing and I asked the Maharshi what he felt about it. He laughed and replied that it pleased them to sing and made them feel peaceful.

Next morning again I sat in the hall. There was a yogi with matted hair. The diplomat was there, sitting in concentrated thought. I wondered whether I should imitate him, but I did not feel like meditating. Suddenly the Maharshi looked at me with great intensity. His eyes took possession of me. I don’t know how long it lasted, but I felt at ease and happy.

Afterwards, a disciple who had been with him for twenty years told me that this was the silent initiation. I felt that it probably was, but I wanted to make sure, so in the hall that afternoon I said: “Bhagavan, I want your initiation....”

And he replied: “You have it already.[1]”

Knowing myself and feeling anxious about what would happen when I left his presence, I asked for some sort of reassurance from him, and he replied very firmly and decisively: “Even if you let go of Bhagavan, Bhagavan will never let go of you.”

There was some whispering and exchange of glances when people heard that. The diplomat whispered to a Muslim professor[2] who was sitting beside him and then the latter asked the Maharshi whether this guarantee applied only to me or to him also. The Maharshi did not look very pleased but replied briefly: “To all.”

Nevertheless, I felt that there was something intensely personal in it, that it had been a confirmation of the initiation and a direct, personal guarantee of protection. Certain it is that, whatever else may have happened, there has been no day since then when his face or his words have not influenced me.

Footnote:

[1] This is the only occasion on which I have ever known the Maharshi give an express verbal confirmation of having given initiation to anyone. It will be noted that the request was phrased in such a way that the confirmation could be given without any statement implying duality. [Editor][2] perhaps Dr.M.Hafiz Syed

Blessed Days in the Company of Viswanatha Swami

Part II

MY next opportunity to visit Sri Ramanasramam came in January of 1979. Those were pre-digital days, so we seemed to move about armed with cassette tapes and shoebox tape recorders. My hope on this visit was to record Viswanatha Swami’s reminiscences and recitations, and to memorialize his spiritual wisdom on tape for friends and future devotees. So, with this noble plan in mind I sewed a shoulder bag that would just fit a shoebox tape recorder. I knew that Swamiji received visitors in the afternoon before Vedas and so — armed with my trusty shoebox tape recorder concealed in the bag — I entered the room and sat beside him. Gently, I asked if he would share some of his early experiences with Bhagavan and just at the moment he began to say something, I slid out the recorder a tiny bit and pressed the record button. Was he to be so easily fooled? Of course he heard the sound of the button being pressed! Swami immediately looked down at the recorder peeking out of the bag and told me to turn it off, foiling in a second my carefully laid plan.

By nature all kindness and compassion, however, Viswanatha Swami, in the midst of numerous literary projects and voluminous editing for The Mountain Path and in spite of his own weakened physical condition, carved out an hour each day to give me a “Sanskrit class”. Those were blessed and happy hours indeed, when I sat by his side and he shared with me Sanskrit slokas and songs — first and foremost, the compositions of Bhagavan, sacred compositions of ancient Vedic tradition and his own verses as well — written with the guidance of Bhagavan and Kavyakantha Ganapati Muni. In fact, he filled up a notebook for me with the compositions of Bhagavan and other slokas, and the day before I left he presented this priceless treasure to me with the name “Bhāmatī” inscribed in the front.

In my case, Viswanatha Swami used kindness to encourage detachment, friendliness to encourage dispassion. My attitude with him was one of complete and childlike trust, like that of a young girl with her father. This was confirmed on one occasion when I went to Swamiji’s room for my daily “Sanskrit class”. I took my seat by his side as usual. Unexpectedly, a Kashmiri gentleman had come that day, and Swamiji enthusiastically said to him, “You see how, like a little girl, she feels no shyness to sit by my side? I am an unmarried man, I have no issue, but I have my brother’s children — she is like one of them!” This same solicitude was extended to all and demonstrates his extreme graciousness!

On another occasion after he had advised me not to go on pradakshina, with a mischievous look in his eyes he inquired, “So, did you go round the Hill this morning?” (Naturally, I had not.) He personally intervened when two other devotees in Arunachala Ashrama had intended to climb the Hill before going to Madras the same day. Swami requested them to forego this climb, which they did. Like Arunachala, he could appear aloof. Yet, at one and the same time he was a disinterested witness and a most compassionate father for us.

Sri Bhagavan gave me the grace not to delude myself with the expectation of seeing Swami Viswanatha again in physical form, so how much more poignant was my leave-taking in March of 1979. Swami understood this as well and he could not have been more compassionate. On my next-to-last night, I encountered him pacing the verandah in front of Sri Bhagavan’s Samadhi. Mrs.McIver approached us and told me of Swamiji: “He is my oldest friend here — he took me on my first pradakshina.”

“He may not be my oldest friend, but he’s my ‘best friend’.” I replied. Laughingly, Swamiji graciously exclaimed, “Friend, child, daughter, niece — she is all these to me. I feel she is my own child.” How these blessed parting words assured me of Swamiji’s continuing solicitude and interest in me and all of my fellow devotees.

In my humble experience, it sometimes happens that what appears to be going on outwardly may be quite different from what is happening inwardly. To all appearances, I was a young woman studying Sanskrit at the side of a gracious old man. Yet there was never a time that I was not aware that I was in the presence of a rare and great soul, in the presence of one of burning dispassion and immaculate renunciation whose experience of the Self was firmly established, yet clothed in the guise of an unassuming devotee. On one occasion I had requested Swamiji to narrate some incidents from his association with Sri Bhagavan. Significantly, he remained silent some moments and then prefaced what he had to say with the words: “Sri Bhagavan has given me the experience that He is none other than my own Self. He is not external to me.”

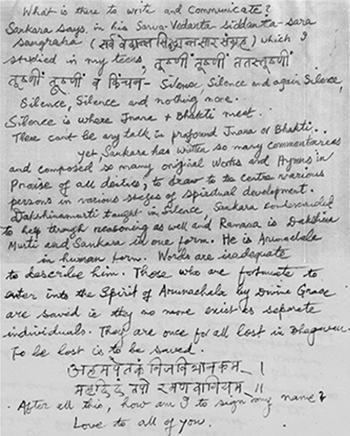

Silence was the context of all that Viswanatha Swami said and did. Many were blessed to feel it to be so which is why people gathered in his room for a while before afternoon Vedic recitations — to dive deep in the atmosphere of silence that his proximity afforded. In this context, and by way of conclusion, I would like to share with you the last and perhaps the most profound message he sent to us. Below is the Sanskrit text from the letter with transliteration and translation.

sarva vedānta siddhānta sāra saṁgraha

The Quintessence of Vedanta

तूष्णीं तूष्णीं ततस्तूष्णीं तूष्णीं तूष्णीं व किंचन ।

tūṣṇīṁ tūṣṇīṁ tatastūṣṇīṁ tūṣṇīṁ tūṣṇīṁ va kiṁcana |

"Silence, Silence and again Silence, Silence, Silence, and nothing more.

अहमपेतकं निजविभानकम् ।

महदिदं तपो रमणवागियम् ॥

ahamapetakaṁ nijavibhānakam |

mahadidaṁ tapo ramaṇavāgiyam ||

All ego gone, Living as that alone

Is penance good for growth,

So sings Ramana, the Self of All.

Mauji Bhagat (The Happy-Go-Lucky Devotee)

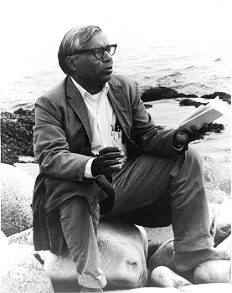

Arunachala Bhakta Bhagawat, the founder of Arunachala Ashrama, was born in a remote village of Bihar. In spite of his education, travel and long residence in America the simplicity of his village humor and wisdom was always on display.

Remembering him on April 10th, the 16th anniversary of his passing, we recalled one of the many simple village stories he delightfully read and translated to us over the years.

The following story, taken from a Gita Press book, Ek Lota Pani, is an English translation.

In the village Khagipur, in the district of Gauhati, there lived a cowherd boy. His name was Mauji (Happy-go-lucky)! He, indeed, was a happy-go-lucky boy! He chose to be a cowherd. This story is from the time when Jahangir was the ruler of India.

One day near the bank of a river he was grazing five cows. These cows belonged to the landowner. He used to get two rupees per month as salary and free food and clothing. He was an orphan, illiterate but exceptionally independent. Once Mauji believed something to be true – even if it were absolutely false – he would stick to it like an ant. He would be totally fixed in whatever he believed to be true. However, he did not have the discrimination to differentiate between truth and falsehood because he was devoid of satsang. The one who does not partake of satsang remains a fool, even if he is very learned. In this world, truth and falsehood have been mixed like water and milk. Only satsang enables one to distinguish between the real and the fake.

One day, while sitting under a mango tree, Mauji was humming a bhajan. Soon a pandit with a long tilak (an ash mark) on his forehead arrived there carrying a shoulder bag. It was past noon and the pandit parked himself near Mauji. He took a dip in the river and a pulled out a clean dhoti (a long wrap-around for men) from his bag. Then he sat cross-legged and closed his eyes. He clasped his nostrils with his right hand and sat there for a long time. Then he snacked on two moong laddus (sweets), had a glass of water and was about to leave when Mauji said, “I bow to you Panditji Maharaj.”

Panditji: Blessings!

Mauji: Where do you live?

Panditji: Kesampur

Mauji: Where are you headed to?

Panditji: Daulatabaad. My disciples live there.

Mauji: If you don’t mind, may I ask you a question?

Panditji: Go ahead.

Mauji: A little while ago, what were you doing holding your nose?

Panditji: I was having a darshan (vision) of Bhagavan (God).

Mauji: Alright! That’s it!

Panditji soon left.

Mauji had only one dhoti, so he undressed, jumped into the river and took a dip. He put on his dhoti again and sat cross-legged in meditation like Punditji. He closed his eyes and held his nose. When after a short time he didn’t see anything, he thought, ‘If Panditji could see God, why can’t I?’ Then he held his nose even tighter, thinking that perhaps he didn’t press it hard enough! But nothing! Soon he was breathless. But Mauji thought, ‘Even if I die, so be it. Unless I see God, I won’t breathe.’ It became absolutely unbearable. He thought, ‘Sure, I love my life but not more than God!’ He held his nose even tighter. The string of prana (breath of life) is connected to God’s abode! The alarm of his impending death reached the throne of all lives. God saw that a cowherd’s son is sitting under a tree holding his breath! When enquired by Vishnu, Maya (the world) explained by narrating the exchange the boy had with the Pandit. After listening to the whole story God thought that it’s not yet Mauji’s time to die, so he should be blessed with His darshan (a vivid encounter). God appeared before Mauji and said, “Open your eyes! I have appeared!”

The moment Mauji heard these words he opened his eyes, loosened the grip on his nose, let out his breath and asked, “Who are you?”

God: Me? God!

Mauji: What’s the proof that you are God?

God: You can ask for whatever proof you wish.

Mauji: Let me get hold of that Pandit. I’m sure he hasn’t gone too far. I have never seen you before but he has, so if he confirms that you are God, I will believe that you are God!

God: As you wish.

Mauji: But what if you escape while I am gone to get hold of Panditji?

God: No, I will wait right here.

Mauji: How can I trust a stranger? I will tie you up tight to this mango tree.

God: All right! Tie me up!

Mauji got up and made a long rope from all the ties he had for the cows. Poor God walked over and stood right next to the mango tree as requested. Mauji tied Him up tight without any hesitation. Then he turned and ran after Panditji. After some distance he could see him and yelled out, “O! Panditji Maharaj! Panditji Maharaj! Come and see if it’s the same God you see or is it someone else? I have tied him to that mango tree!” Panditji heard him but couldn’t understand a word of what he was yelling. He looked over his shoulder and saw that the boy he had seen at the river a little while ago was running towards him. Panditji thought this guy is young and he being old, perhaps he was coming to steal his bag. He hurried forward faster. But Mauji was determined and caught up with him. He held his hand and dragged him back close to the mango tree.

Mauji: Tell me, Panditji, this is God, right?

Panditji looked everywhere, but all he could see was a rope tied to a mango tree.

Panditji: Where is God?

Mauji: Can’t you even see in broad daylight? Don’t you see him tied right there?

In order to get out of this situation, Panditji lied and said, “Yes that’s Him.”

Mauji insisted, please go close to Him and make sure. I don’t want you to say later that it wasn’t God!

Panditji couldn’t see God but again he just said, “Yes, yes that’s it. Its God.”

Now, Panditji was freed and left. Satisfied, Mauji untied God and touched his feet.

God: That Panditji is not my bhakta (devotee). He is a hypocrite.

Mauji: Then why do you give darshan to a hypocrite?

God: I have never given darshan to him.

Mauji: Hmm! He said he sees you every day and just moments ago he identified you.

God: Neither did he see me today, nor has he ever seen me before. He is a liar.

Mauji: But his lie has made it possible for me to meet the Truth, to see You. He may be a hypocrite but for me he is my guru.

God: Tell me, what do you want from me? My darshan cannot be without some good.

Mauji: I wish that whenever I close my eyes, after taking a bath and holding my nose, you appear before me.

God: Granted. So shall it be.

Mauji: You have blessed me with your kindness. Please grant me one more, since I am asking.

God: Ask me.

Mauji: When Panditji holds his nose, please appear before him too.

God: Then he would be reformed, because those who have my darshan cannot remain a hypocrite.

Mauji, you are indeed virtuous! You have lifted yourself and your Guru, too. It is usually the Guru who lifts a disciple but today a disciple has lifted his Guru.

After one year the same Panditji tread the same path. Mauji was herding his cattle at the same place when they both saw each other, and Mauji exclaimed, “Prostrations, Guruji!”

Panditji: Guruji, prostrations!

Mauji: You are my Guru because you made it possible for me to see Bhagavan (God).

Punditji: You are my Guru because you, in fact, made me meet God.

Mauji: You are a Brahmin and I’m just a herdsman.

Punditji: You are a Brahmin and I am a herdsman

Mauji: I was dumb. You made me a Pundit!?!

Punditji: Hypocrite I was, you made me a bhakta!

Mauji: Whatever had to happen, happened. We are each other’s Guru and we are each other’s chela (disciple)!

Punditji: I’ve given up the profession of being a spiritual leader. Now you also give up being a herdsman.

Mauji: What shall we do then?

Punditji: We will spread the name of Rama (God) from door to door. You play the drums and I will play the cymbals.

Mauji: Yes, we will sing bhajans, together.

Punditji: Yes, in the sacred water of Ram-nām we will bathe, and bathe the world in it too.

Mauji: What shall we call ourselves?

Punditji: You will be named Punditdas (servant of a Pundit) and I will be named Aheerdas (servant of a herdsman).

Mauji: Because your Guru is an Aheer (herdsman) and my Guru is a Pundit.

Punditji: Yes, indeed, Aheerdas!

In the district of Gauhati two sadhus were seen singing bhajans, moving from village to village. When they sang bhajans they were immersed in ecstasy and the listeners were absorbed too. Thanks to Bhagavan and thanks to His devotees. Strange are His ways.