Spontaneous Awakening

Readers of The Mountain Path already know Douglas E.Harding from his article, 'Self-Enquiry, Some Objections, Answered', in our issue of April, 1964. In the present article he tells a story showing how "the Spirit bloweth where it listeth," independent of forms and traditions.

This is the first article to be published about a very remarkable (yet outwardly very unremarkable) young Englishwoman. It is a brief description of how her life has, almost without warning and practically overnight, been altogether revolutionised, written by a friend who has throughout been her close companion and sole confidant. Its purpose is to encourage all serious spiritual seekers, and particularly those who imagine that true Illumination is necessarily a long way off, or almost impossibly difficult, or the preserve of some particular sect or religion, or indeed the product of any religious discipline at all. The case of Helen Day Scrutton shows that you never can tell. It brings home to us afresh, in our own time and circumstances, the tremendous reality of what Masefield calls the "glory of the lighted soul", demonstrating in the most concrete and vivid way the joy and splendour that await us all just around the corner of our life : no, press right in upon us here and now, as we read these words. We can't be too often reminded, not only of the existence of our Infinite Treasure, but also of its perfect accessibility and naturalness, its homeliness and handiness and immense practicality, and above all its aliveness. To remain satisfied with anything less than This just doesn't make sense.

It was about four years ago when I first met Helen. Since then we've worked very closely together all the while in the same organisation, seeing a great deal of each other during the day, and increasingly when off duty. I should know her fairly well.

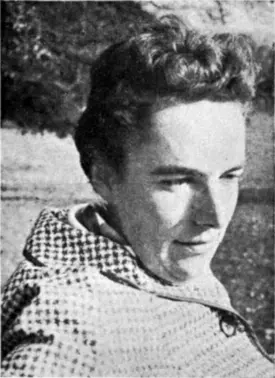

Let me try to describe the first impression she made. (If this sounds like an employer's testimonial, why that's what it is, after all - but with what a difference !) I saw Helen as a lively, healthy-minded and healthy-bodied, very intelligent but not at all intellectual woman in her late twenties. In repose, her face was on the stolid side, with splendid eyes, but what brightness when she smiled ! She proved quick to learn all the complex details of her job, practical and level-headed, conscientious after her own independent fashion, humorous, tactful and easy with people as a rule, and unusually patient and self-controlled when things went wrong. In short, a Treasure!

No nonsense about Helen - not even powder or lipstick (that I've detected, anyway) - athletic, clear-complexioned, scrupulously turned out, good-looking in an unobtrusive way, not pretty, The ideal confidential secretary and a charming friend.

But I still felt obliged, in the end, to take Helen to task. It seemed to me that she didn’t know her own value. Her job, though a responsible one, could lead nowhere, and she was clearly capable of something much more creative. Her interests - tennis, swimming, fairly wide but desultory reading (which included few religious books and certainly no mystical ones), listening to music of all kinds, some youth-club work (neglected in recent years), regular but unenthusiastie Church-of-England attendance, and the sort of superficial friendships such a cheerful and popular young person would naturally make - these seemed not to reflect her true character and potentialities. I had the cheek to tell her so, rather often. She offered no comment. But she did, eventually, make serious plans to train as a probation officer. And a wonderful one she would have made.

We were fond of each other, without seeming to make any deep contact. Inevitably she got to know about my concern with spiritual matters, but no pressure at all was exerted: I had no desire to steer her in that or any other direction. And certainly she seemed a most unlikely subject - altogether too normal and down-to-earth, not .a spiritual type at all! (In a certain sense, I still think she isn’t, thank God!) Besides (and how unlike so many of us, how spiritually unfashionable, almost reprehensible!) Helen solemnly assured me that she'd loved and been loved by her admirable parents, led a happy childhood, enjoyed her grammar school (she must have been a fine head prefect), and found her office work pleasant enough. Her most testing experience was the loss of her fiance ; and in fact death, or some other insuperable obstacle, has intervened to break no fewer than three engagements. (The significance of this seeming tragedy isn't lost on her, of course, and she is now more than happy to remain single and quite unattached to any man.) No, Helen is altogether too well-balanced a young woman, lacking almost all the current credentials - no tangled complexes, no awful history of suffering, no prolonged and bitter struggle - to be what in fact she is, a most gifted mystic. (I suspect, really, that the best masters of the spiritual life were, like Ramana Maharshi, specially sane and healthy, the reverse of abnormal). Yet when she typed for me some article about mystical religion she scarcely seemed interested, and had less than usual to say. It’s true that when she came to our house for an evening, or to stay for a day or two, she got into the habit of picking up one of my books on Vedanta or Sufism or Zen and reading it; and I noticed that she always finished what she'd started, however difficult or dull the author. She also read my own little book 'On Having No Head' - but made nothing of it, I now learn. At the time, she was too polite to say so.

This brings me to the real beginning of the story - to May, 1964, and what we sometimes call the ‘Ten Days that Shook the World’. Helen was off to Eastbourne for the Whitsun holiday, and anxious to take some of my books with her ; I remember these included Aldous Huxley’s "Perennial Philosophy". Evidently she had become really interested. Something was happening.

A new Helen came back, deeply stirred and now eager to talk. “Douglas,” she said (and I think I can quote almost the exact words : after all, it was only a few months ago), “I've just realised something : all this applies to me! And of course absolutely nothing else matters!” She explained how the whole thing had, after a few weeks of inward search, accompanied by increasing concern and tension, become perfectly clear to her : now it made sense, she'd taken it in, taken it to heart, and this was quite overwhelming. Those evenings that followed, when she walked alone for hours in the park, wearing dark glasses so that people shouldn’t see that she was crying for joy at the wonder of her discovery, the transformed world, the colours that positively sang, the exquisite beauty of everything (yes everything, including the 'rubbish' in those wire baskets) ! Morning after morning in the office, I was to hear from Helen this kind of story. Often - indeed, usually - it was : "No sleep at all last night, Douglas: time just flashed by : again it was just joy, oneness, clarity, from the time I lay down to when I got up for breakfast, fresher than if I'd slept the whole night. The extraordinary thing is I never feel tired." I remember her explaining how she left home, and presently found herself at the office half a mile away, and the interval was just brightness, no-thinking, with no recollection of having walked at all. I remember also her trying to explain how, on other occasions, her walking was "just like taking the dog for a walk" - her legs and their movement had been like the dog's, nothing to do with her. It was a wonderfully free-and-easy feeling. Yes, Indeed !

Many other surprises were in store for us. Helen’s tennis, always goodish, immediately became quite remarkably good, to the astonishment of the members of her club — and their greater astonishment and disappointment when she announced that she wasn't going to play any more, after completing the games that had already been fixed for her. Those games she won brilliantly, automatically. To me, her explanation was that she did nothing, her racquet did it all, the game played itself with a skill and ease she'd never known. Part of the secret (we agreed) must have been that whereas before she had always wanted very much to win, now she had no feelings at all one way or the other, and the resulting relaxation naturally helped her performance, But she insisted that she didn’t do anything again, she was the onlooker. (And, lest anyone should suppose she'd been reading Herrigel’s “book on Zen archery, I happen to know she still hasn't done so.)

All ambition, all other interests, had gone. The probation-officer project was dropped at once. In fact, Helen even discussed with me the possibility of getting a routine job, such as a copy-typist’s, which would interfere as little as possible with her new life. This idea, however, was soon scrapped because she found that her work, however complicated, practically did itself if she didn’t interfere. More remarkably, it did itself (I noticed) even more accurately and rapidly than before. (It had to: we spent so much time in the office on other business, on our real business !) “Just let things happen,” she said, “and they turn out perfectly. Do them deliberately, plan ahead, and they go wrong.” Before, she'd generally been rather pressed for time: now, she had. all the time in the world.

I’m sure everyone in the office noticed the change in her. One man who (somewhat unreasonably, I thought) she hadn’t much liked, was now “quite nice really, and it was all Helen’s fault.” It was plain how happy she was. People asked what had come over her: she looked like a cat that had just had kittens, someone remarked. Not that she was changed beyond recognition : thank goodness the old, charmingly informal Helen, with most of her personal quirks, was ‘still with us. There was nothing odd or unnatural or spectacular about the change in her: if anything, she was more truly normal and natural than ever. (So much so that some who don’t know Helen very well, but have preconceived notions of the outward effects of Illumination, naturally doubt whether anything more than a psychological reorganisation, akin to those religious conversions which are common enough, has occurred in her. And, of course, one cannot find in Helen, or in any other, what one hasn't begun to find in oneself.) Her ego had never stuck out very far; now. it was imperceptible — except, perhaps, for occasional irritation with some particularly difficult client, or employer! “No, it comes back occasionally,” she confessed to me, “but now I see clearly when it’s there.” (Lately, I think even this rare and trivial ego-symptom has disappeared, though she remains capable — we've just discovered — of momentary, anger.) Obviously she no longer had moods. but was permanently happy whatever happened. And she had.no need to tell me about her changed feeling for people. Her heart really went out to them; she enjoyed and loved them, not equally (it’s true) but far more than she'd ever done before. How many times she's walked into my office exclaiming : “What a wonderful person so-and-so is, Douglas !” — and her glowing face and shining eyes were eloquent of her feeling. At the same time she no longer saw us through the distorting spectacles of self-interest, but as we really were: and in some instances this shocked her. Unsuspected weaknesses and meannesses were now quite plain, Hidden motives showed themselves. She was no longer deceived.

And Helen had no time for the old social round, no time for idle chatter or hobbies or amusements — no time at all except for the one thing that mattered, and all her time for that alone! She somehow got out of those (always rather pointless) little lunch parties, all reading (including newspapers) except for books on the subject, her tennis of course, and even her swimming in the end.

It was the swimming that warned us that her tremendous spirit might be asking too much of her body. One evening in late July I drove Helen to her beach-hut, and as we parted something made.me beg her to be very careful. She wasn’t. Next morning at the office she told me how rough the sea had been, and how she'd got out beyond the breakers only to become mixed up with a large stinging jellyfish, and then (to cap it all) realised the strength of the current pulling away from the shore. She remained perfectly calm and content (these are roughly her own words) and just waited to see what would happen. Without any effort on her part, her body somehow took her shorewards, where a large wave just picked her up and deposited her quite gently on the beach. There she was surprised to find herself trembling and exhausted.

Helen had become much too careless of her health. She walked and walked goodness knows far, though always with that unhurried, loose-limbed, easy gait of hers, which is almost like the lope of some animal. She ate too little and irregularly, and rapidly lost weight, Night followed night without sleep — her new-found “happiness was so great. (When, however, she did at last sleep it was, from then right up to now, always dreamlessly. This surprised her, because she hed been used to dreaming a lot. It interested me, too, because, unlike her, I knew that one of the marks of the illumined is that they dream little or not at all.) After a few weeks of living like this, no wonder she went down with an attack of her old complaint of anaemia, and had to take it easy — physically. Spiritually, things continued to get better and better, though she couldn’t understand how that was possible! If she then read and talked much less, this wasn't because she was tired, but so spiritually fresh that talking and reading books about It had become rather pointless. She was their Author ; she was It.

The weeks following Helen's return from Eastbourne had been a time of ecstasy. Let me quote her own words, typical of that period, hastily scribbled on a scrap of paper without regard for grammar or punctuation, and only just rescued from destruction by me:

Light dazzling pure light clear brilliance A feeling of being carried away weightlessness

11.00—5.30 time non-existent endless eternity

No physical tiredness sleep out of question feeling of exhilaration and peace. Happening for the first time like fog or a curtain dropped completely away

This is all that matters for always

There must be a heaven on earth

Why explain? Words are useless and unnecessary, but the knowing constant

I did suggest, at the time, that this phase of Helen's illumination (we called it the “gorgeous technicolour’ phase) would develop into an even profounder, more natural, and virtually permanent state. And this soon happened, in fact. Is it possible for me to describe that state ?

Perhaps it would be useful to summarise here by mentioning the four aspects — or moments, or stages — into which we have often divided (artificially, for the sake of description) the essential experience :

1. The VOID. This is the KEY, the indispensable basis. It means clearly seeing, at will, even all the time, that right here one is totally headless, bodiless, mindless, and in fact Nothing whatever.

2. LOVE. The result of this absolute contraction is an equal and opposite expansion, a great outward surge which leaves nobody and nothing out.

3. The ALONE. As thus all-embracing, one is the One, quite solitary, free, independent. These foolish words can give no idea of the Homecoming.

4. MYSTERY. Thus actually to be the Alone, Self-originating and Self-sufficient, is unspeakable wonder.

These four may give some slight clue to an Experience which is, of course, neither Helen’s nor mine, but that of the One who is our Self ; but really they won’t do at all — they only import complications into what is perfect Clarity and Simplicity. Between this Clear Seeing, and the finest description of it, there must always remain an infinite gap. It isn’t merely that words can’t reveal It: they are what hide It.

Of course a certain amount of talk helped at the beginning. Just being with Helen, ready with encouragement and understanding when she needed them, and the occasional explanation of some puzzle, did make a good deal of difference. And I was able to put her on to those few— but very few — books which have been written out of firsthand experience, and protect her temporarily from the thousands that have not. I introduced her to Eckhart, Ruysbroeck, Rumi, the Upanishads, Sankara, Ramana Maharshi, Lao-tzu, Huang-po and Hui-hai: notice I was careful not to plug any one tradition : it was imperative that Helen should find her own affinities. In fact, she was unable to pick and choose between them: each displayed for her an indispensable aspect of a single clear pattern. (Only, perhaps I should add, Ramana Maharshi has a very special appeal for us both.) Helen devoured these books, ignoring always the merely geographical and historical accidents and grasping the common essence. She had no real questions to ask me then, none at all.

A miracle it remains for us both, how suddenly and completely this wonderful thing has happened. But even miracles have some background, and obviously this one called for further investigation. How was it possible for Helen so rudely to jump the spiritual queue? We thought of the years of anxious searching, of austerities, marathons of meditation, which are traditionally reckoned - the price of any real Illumination, and we marvelled. Was Helen one of those very rare exceptions to the rule? Then we discovered — not, of course, an explanation of her gift and her grace, but something of its history. She’d been a dark horse all along. Understandably, there’d been, throughout childhood and youth the flashes, the brief but lovely previews of heaven; but in addition something much more remarkable and significant. From her earliest schooldays onwards, she’d been in the habit of going off on her own, swimming, rambling, just sitting; and this solitude became more and more an essential part of her life-pattern. Latterly, her beach-hut had provided a convenient retreat where she used to sit, quite alone for hours, on summer evenings and at weekends. I asked what she had thought about. She replied — bless her ! — just as if it were a stupid question to have asked: “Why, nothing! I just sat!” “Dozing?” I enquired. “Of course not. Quite wide awake, with an empty mind.” Just like that! It’s true the fact that here was something odd about this behaviour had already dawned upon her: her friends were inclined to regard it as self-indulgent, or even morbid. Not that this had at all deterred Helen: the pleasure of merely sitting there was its own reward, and increasingly necessary to her well-being. But certainly it never occurred to her that this state of no-mind might have some religious or mystical significance, or was much more than an idiosyncrasy. If anyone had told her then — as I did later — that after months and years of sitting meditation a yogin would be doing well if he could avoid all wandering thoughts for a few minutes, whereas Helen was able to shed them for as long as she liked — why, if anyone had told her this she would have thought he was just teasing ! I don’t mean to imply, of course, that this strange accomplishment of hers was ‘sitting meditation’ in the full sense of that term, or spiritually mature: it was, as yet, far from Self-aware. But what better rehearsal for the Self-awareness she now enjoys could be imagined ?

Well, that is Helen’s story to date, in brief. It will be pointed out, of course, that having got off to a wonderful start, she still has a long, long way to go. In one sense, it’s true : there’s no end to This. But in a much deeper sense it’s the lie. She has nowhere to go. She’s where she has always been — HERE. What’s more to the point, she has the nerve to see it, and to say she sees it, and to live every moment accordingly. That’s all that matters.

For all genuine seekers, and particularly for us in the West, Helen should prove a huge encouragement. She doesn’t want to be known — or unknown, for that matter — and is virtually indifferent to praise or ridicule.