As I Saw Him - No.1

TO TRY TO DESCRIBE my reactions when I first came into the presence of Bhagavan is difficult. I felt the tremendous peace of his presence, his graciousness. It was not as though I was meeting him for the first time. It seemed that I had always known him. It was not even like the renewal of an old acquaintanceship. It had always been there though I had not been conscious of it at the time. Now I knew.

It was only afterwards, when I had dwelt in India for some time, that I began to realise how gracious Bhagavan had been to me from the very first. And this attitude of mine was to my advantage. Bhagavan responded to people's reactions. If you behaved absolutely naturally, with no strain, Bhagavan's behaviour was similar.

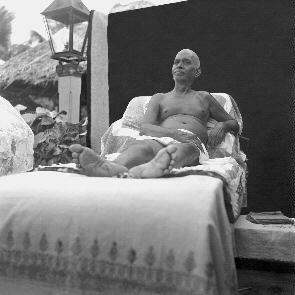

When I entered the Hall for the first time, Bhagavan was seated on his couch, facing the door. It was about seven o'clock and he had just returned from his stroll on the Hill. Bhagavan adored the Hill and was never happier than when wandering about its slopes. He greeted me with his lovely smile and asked if I had had my breakfast, and then told me to sit down. Bhagavan talked to me the whole morning till it was time for the midday meal. He asked me many questions about myself and my life. All this seemed quite natural. Later I was to discover that he usually greeted visitors with a glance, made a few remarks and then remained silent, or waited for them to put their doubts and question him so that he might answer. Or often he appeared unconscious that anybody had entered, though this was only in appearance, for he was always fully conscious.

I found when I had been in the Ashrama a short time and was beginning to know my way about, that the best time to catch Bhagavan alone was at one o'clock in the afternoon when he came back from the Hill. Everyone who could would have slipped away for a siesta, except for one attendant whose duty it was to remain with Bhagavan in case he needed anything. This was before the days of electricity so a punkah had been hung just over Bhagavan's couch and this would be kept in lazy motion by a sleepy attendant who was himself dying to run off and have a sleep. At times I would take his duty and let him go, at others I would sit up near the head of Bhagavan's couch and talk to him. It was during these quiet hours that he instructed me and those quiet hours spent with him then were the most valuable of all.

Bhagavan was a very beautiful person; he shone with a visible light or aura. He had the most delicate hands I have ever seen with which alone he could express himself, one might almost say, talk. His features were regular and the wonder of his eyes was famous. His forehead was high and the dome of his head the highest I have ever seen. As this in India is known as the dome of wisdom it is only natural that it should be so. His body was well-formed and of only medium height, but this was not apparent as his personality was so dominant that one looked upon him as tall. He had a great sense of humour and when talking a smile was never far from his face.

He had many jokes in his repertoire and was a magnificent actor; he would always dramatise the protagonist of any story he related. When the recital was very pathetic, Bhagavan would be filled with emotion and unable to proceed. When people came to him with their family stories he would laugh with the happy and at times shed tears with the bereaved. In this way, he seemed to reciprocate the emotions of others. Bhagavan never raised his voice and, if he did occasionally seem angry, there was no sign of it on the surface of his peace. Talk to him immediately afterwards and he would answer calmly and quite undisturbed. He would never touch money, not because he hated it - he knew that for the purpose of daily life it was necessary - but he had never any need of it and was not interested in it.

People said that Bhagavan would not talk but this was untrue, as were many other foolish legends about him. He did not speak unnecessarily and his apparent silence only showed how much foolish chatter usually goes on amongst ourselves. He preferred every sort of simplicity and liked to sit on the floor, but a couch had been forced upon him and this became his home for most of the twenty-four hours of the day. He would never, if he could help it, allow any preference to be shown to him and in the dining room he was adamant on this point. Even if some special medicine or tonic were given to him he wanted to share it with everybody. "If it is good for me, then it must be good for the rest," he would argue and make them distribute it round the dining hall. He would wander out to the Hill several times a day, and if any attachment to anything on earth could be said of him, it was surely an attachment to the Hill. He loved it and said it was God Himself.

Approached in the right way, Bhagavan would advise, though the majority of people who moved with him would deny it. They had never tried in the right way or, more probably, never intended to take permission at all. They thus bluffed themselves into thinking that he had given them leave and in this way did what they themselves had intended to do.

Bhagavan was invariably kind to all animals though he did not like cats or, I believe, mongooses; this was principally because the cats hunted his beloved squirrels or chipmunks. These squirrels used to run in and out of the Hall window over his couch and even his body. He would feed them with nuts and stroke them; some of them even had names. Their chief ambition seemed to be to make nests behind his pillows so that they might bring up their families under his protection.

On February 5th, 1949 the tragedy of the final illness had its inception. Bhagavan had been frequently rubbing his left elbow which was causing some irritation. His attendant inspected this to see what was the trouble and found a small lump the size of a pea. The doctor decided that it was only a small matter and should be removed by a local anaesthetic, and the operation was quietly performed in Bhagavan's bathroom one morning just before the meal. This was the beginning of the end. The curtain on the last act was slowly descending. The growth turned out to be sarcoma.

I feel that I should not let the occasion pass without saying a word to those who doubt the continued presence of our Guru amongst us. Though we talk as though he were dead, he is indeed here and very much alive as he promised, in spite of appearances.

Often visitors have remarked, "But one can feel him more strongly than ever." Of course, one misses the physical presence, the opportunity to ask questions, the delight of his greeting, the humour of his approach, and most of all his understanding and sympathy. Yes, one certainly misses all that, but one never doubts for a moment that he is still here when one has taken the trouble to visit his tomb.

When Sri Ramana lay dying, people went to him and begged him to remain for a while longer as they needed his help. His reply is well known:

"Go! Where can I go? I shall always be here."

The power of Sri Ramana, who gave up his physical form, has not diminished. He is everywhere, like the light in a room shed by an electric bulb. But the light is found to be far stronger near the bulb, the source of light, than in any other part of the room, though no spot is in darkness. What wonder, then, if the power of our Guru is found near the place where his body is interred.

Self Realization

We usually identify ourselves in terms of name and form: "I am John, forty years old, 180 pounds. I have this job and live with that family, etc." This is all quite natural.

But those fortunate few who are destined to look deeper into their own nature will discover a Self much different from what outward circumstances dictate. The eternal, free and perfect Self is always present within us, while the veils of body-identification prevent us from experiencing who, in fact, we really are. The Maharshi stresses this point again and again.

In the following extract from Gems from Bhagavan, we are reminded of this truth and inspired to realise the True Self.

THE STATE WE CALL realization is simply being oneself, not knowing anything or becoming anything. If one has realised, he is that which alone is, and which alone has always been. He cannot describe that state. He can only be That. Of course we loosely talk of Self-Realization for want of a better term.

That which is, is peace. All that we need do is to keep quiet. Peace is our real nature. We spoil it. What is required is that we cease to spoil it. If we remove all the rubbish from the mind, the peace will become manifest. That which is obstructing the peace must be removed. Peace is the only reality.

Our real nature is mukti. But we are imagining that we are bound and are making various strenuous attempts to become free, while we are all the time free. This will be understood only when we reach that stage. We will be surprised that we frantically were trying to attain something which we have always been and are. It is another name for us.

Our wanting mukti is a very funny thing. It is like a man who is in the shade voluntarily leaving the shade, going into the sun, feeling the severity of the heat there, making great efforts to get back into the shade and then rejoicing 'How sweet is the shade. I have after all reached the shade!' We are doing exactly the same. We are not different from the reality. We imagine we are different, i.e., we create the bheda bhava (the feeling of difference) and then undergo great sadhanas to get rid of the bheda bhava and realise the oneness. Why imagine or create the bheda bhava and then destroy it?

It is false to speak of realization. What is there to realise? The real is as it is, ever. How to realise it? All that is required is this. We have realised the unreal, i.e., regarded as real what is unreal. We have to give up this attitude. That is all that is required for us to attain jnana. We are not creating anything new or achieving something which we did not have before.

Effortless and choiceless awareness is our real state. If we can attain it or be in it, it is all right. But one cannot reach it without effort, the effort of deliberate meditation. All the age long vasanas (impressions) carry the mind outwards and turn it to external objects. All such thoughts have to be given up and the mind turned inward. For that, effort is necessary, for most people. Of course everybody, every book says 'Be quiet or still'. But it is not easy. That is why all this effort is necessary.

There is a state beyond our efforts or effortlessness. Until that is realised effort is necessary. After tasting such bliss even once, one will repeatedly try to regain it. Having once experienced the bliss of peace, no one would like to be out of it or engage himself otherwise.

You may go on reading any number of books on Vedanta. They can only tell you 'Realise the Self'. The Self cannot be found in books. You have to find it for yourself in yourself.

If we regard ourselves as the doers of action we shall also be the enjoyers of the fruits of such action. If by enquiring who does these actions one realises one's Self, the sense that one is the doer vanishes and with it go all the three kinds of Karma (viz. sanchita, agamya and prarabdha). This is the state of Eternal Mukti or Liberation.

The power of the sage's Self-Realization is more powerful than all occult powers. To the sage there are no others. But what is the highest benefit that can be conferred on 'others' as we call them? It is happiness. Happiness is born of peace. Peace can reign only when there is no disturbance by thought. When the mind has been annihilated there will be perfect peace. As there is no mind the sage cannot be aware of others. But the mere fact of his Self-Realization is enough to make all others peaceful and happy.

Prominent Publications

A Sadhu's Reminiscences of Ramana Maharshi

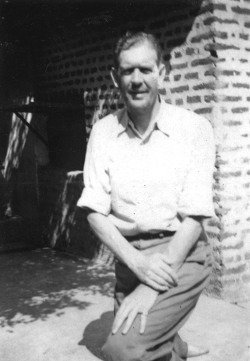

by Sadhu Arunachala (A. W. Chadwick)

The first article in this issue, "As I Saw Him," is a collection of passages from this fascinating book.

When the author was in South America serving as a British army major in 1935, he read Paul Brunton's book, "A Search In Secret India". He was so captivated with the chapters on the Maharshi that he resigned his position and travelled to India, arriving at Ramanasramam on November first of the same year.

This move was not a reckless or impulsive one, for, as revealed in his book, we see him as a mature seeker who had been practising meditation for many years; and, once arriving in the presence of the Maharshi, he felt perfectly at home. In fact, he remained there to his end in 1962.

Bhagavan once commented, "Chadwick was with us before, he is one of us. He had some desire to be born in the West, and that is now fulfilled."

Sadhu Arunachala (the name given to him by the Maharshi) was a man of vast experience and keen intelligence. His grasp of the Master's teachings was impeccable and intuitive. Equally impeccable were his observations and interpretations of certain incidents relating to Bhagavan. He witnessed the Maharshi's approval of a will; Bhagavan's participation in the construction and consecration of the temple over the Mother's grave; and the visit of the celebrated author, Somerset Maugham. On these and other matters he unmasks the true spirit of the Maharshi, constructing before our eyes an unforgettable personality.

This book is naturally captivating and as easy to read as it is to breathe. The reason is that it has been written by an intimate, Western disciple who lived for fifteen years with the Maharshi - physically - and has now been absorbed in Him for all time.

Gems from Bhagavan

Pp.58

Within fifty-eight pages, the compiler has gathered all the salient teachings of the Maharshi and set them forth in thirteen chapters.

A study of this small, precious book will equip the reader with the full breadth and depth of all of Bhagavan's teachings. For example, chapter three, "Mind"; chapter four, "Who Am I? Enquiry"; chapter five, "Surrender"; and chapter nine, "Heart," serve to crystallise the direct method to "Self Realization," which is the title to chapter eight.

An earnest aspirant will keep this book close at hand, for the Maharshi's instructions on almost all subjects of sadhana are readily and clearly presented. Truly, no other book is necessary to understand the teachings and tread the path taught by the Master.

The compiler, A. Devaraja Mudaliar, was a lifelong devotee of Bhagavan, resided with him for some years, and has several other excellent books to his credit. But in this book he has performed a yeoman service by providing us with a veritable wealth in the form of numerous Gems From Bhagavan.

Siva's Tears of Bliss

A letter from Sri Ramanasramam, dated November 28, 1990

"When we arrived in Tiruvannamalai on Sunday evening the rain was pouring down and it continued non-stop until Tuesday morning. There are mud puddles on all the roads, the vegetation is sporting a cheerful countenance and all the tanks and ponds around the Hill are filling up. Today it is cloudy and the peak of Arunachala has been covered with holy ashes [clouds] most of the time. Yesterday we went round the Hill and saw all the streams full and rushing. They seemed like Siva's tears of bliss flowing in streams down His face to His children below...."

Will You Not Let Me Go?

- Will you not let me go?

- Like some insidious druggist you would make

Me come with craven pleading to your door,

And beg you of your mercy let me take

From out your potent wares a little more.

And so,

You will not let me go.

- Will you not let me go?

- Here, in an alien land I pass my hours,

Far from my country and all former ties.

A restless longing slowly me devours

That me all wordly happiness denies.

And so,

Will you not let me go?

- Will you not let me go?

- You tell me, "Yes, I do not keep you here."

That's but your fun. Why else should I stay?

While months pass by and mount up year by year

So that it seems I'll never go away.

And so,

You do not let me go.

- Will you not let me go?

- Nay, I'm a fool, I cannot if I would.

I am your slave, do with me what you will.

That you should all deny, well, that is good.

If it so pleases you. I'll speak no ill.

And so,

Refuse to let me go!

- Will you not let me go?

- I'm only sorry wax beneath your hands.

You've striven long to mould me into shape.

Your endless patience no one understands;

Your boundless love there's no escape.

And so,

You'll never let me go.

- Will you not let me go?

- I'm a fool that I should try to flee,

For here, there is a peace I'll never find

When I the least am separate from Thee;

Then I'll be but a slave to caitiff mind.

And so,

I do not wish to go.