Returning to Ramanasramam

It is 3:30 A.M. I switch off the lights and leave my room, sliding the door bolt and fixing the padlock as I go. It is quiet and dark. I walk east, passing the line of attached guest rooms for single men. I was told that the Maharshi rises at 3:30 a.m. and I am eager to begin my day by resting my eyes on his holy form.

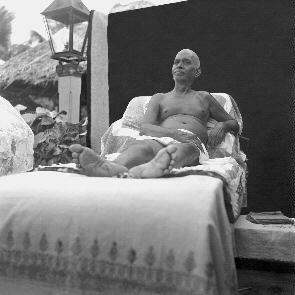

Arriving at his residence, the Old Hall, I find the door is shut. I peek in through the barred window and see into the large room, which is dimly lit by the glow of a hanging deepam. The Maharshi is quietly reclining on the couch facing east, away from me. I join my palms in salutation.

The attendant Brahmachari Ratnam makes his appearance. He opens the door, switches on the light and stands before the Master with palms joined. Imploring the Maharshi's grace, he falls to the floor in full prostration.

I now enter the hall, offer my obeisance, and take my seat against the west wall. Bhagavan's eyes are fixed on me. A shower of peace drenches all the pores of my body; it soaks my mind. This is what is called the sannidhi of the Master, or the holy 'Presence' of the Master. The year is not 1943 - it is the month of July and the year is 1993, fifty years later. And the one whom I call the attendant, Brahmachari Ratnam, is by every means an attendant, servant and devotee of his Lord Ramana. That which is not present now in 1993, but was present then in 1943, is the physical body of the Master. That which the Master repeatedly declared not to be his true form, was the body. My imagining that the Maharshi is still residing in the Old Hall, as he did fifty years ago, is not much different than those who lived with him back then and imagined him to be the body. What is not imagination, now or then, is the reality of the spiritual force of his Divine Presence. That Presence shone forth through the body of the Maharshi and continues to shine forth today in his bodilessness. This is what attracts thousands to Ramanasramam every year, and this is what draws me here again and again.

Every morning Brahmachari Ratnam arrives at the ashram between 3:00 and 4:00 a.m. After passing through the ashram gate in the early morning, he will first prostrate before the closed doors of the Mother's temple, then before the closed doors of Bhagavan's shrine and, just before entering the Old Hall, he will reverently salute the holy mountain, Arunachala. His eyes look straight ahead, his steps are quick and movements controlled and exact. Wearing a white dhoti with a collarless, white, short-sleeved shirt, barefooted, with closely cropped hair this bhakta of Bhagavan quietly moves about the ashram unnoticed. He immediately reminded me of the Maharshi's attendant Madhava, who died in 1946 and is briefly seen in the ashram's archival film and other photographs. For Bhakta Ratnam, Bhagavan's disembodied state is immaterial. His every movement and look proclaims his unalloyed devotion to his Master.

Once inside the Old Hall he follows a consistent routine. With sincere devotion he cleans around Bhagavan's couch, sweeps the hall and then performs arati to the Maharshi's photo. Throughout it all he is seen to be supplicating the Master's grace. Though there was rarely anyone other than me witnessing this scene, it made no difference to Brahmachari Ratnam, for in his vision of the world only he and Bhagavan existed.

Never did I see him speak to anyone unless he was spoken to, and this I saw on only two occasions. Never did I see him idle for a moment. In the early mornings until breakfast he would remain in the Old Hall in prayer and meditation; in the afternoons and nights I would see him sitting in the Samadhi Hall. For many hours each day, in a consistent manner, I saw him sitting in prayer and meditation. If he moved about, it was only to attend the pujas in the Mother's shrine and to ring the bells at Bhagavan's shrine during worship. His whole life is directed to Bhagavan and his sadhana. He is a rare example of one-pointed dedication and devotion, an invaluable asset to the ashram, and an inspiration for all.

It once happened that for two successive days he was absent from the Old Hall in the mornings. Nor did I see him meditating in his regular spot during the day. In his place, an ashram worker would come in the morning, unlock the door of the Old Hall, casually turn on the light, ignite some incense and leave. Feeling his absence, I asked the ashram office manager where he had gone. He was surprised to hear from me that he was gone and mentioned that he is so quiet we hardly know when he is around. Inquiries led to the news that he left for his home to look after his sick Mother and was expected to be away for a week or two.

In the evening, an office assistant gave me the key and asked me if I would open the Old Hall in the mornings during Brahmachari Ratnam's absence. Officially, the hall would be open only at 5 a.m., but during all my visits to the ashram I noticed there were always some aspirants who desired to come to the Old Hall earlier, and it would invariably be open. The Old Hall is the one place in the ashram where most visitors and devotees prefer to sit and meditate. The Maharshi lived there for nearly twenty-five years and the atmosphere still breathes of his Presence. Balarama Reddy, an eighty-five-year-old devotee living in the ashram, described to me his experience in the Old Hall: "There was something tangibly distinct in Bhagavan's hall. When we walked into it and sat down we immediately felt like we had entered a different sphere of existence. It was like the world we knew did not exist there. Bhagavan's Presence, his other-worldliness, would so envelop the atmosphere. When we walked out of the hall we again would be confronted with the old world we knew too well."

On this visit I requested the ashram manager to provide me with a room inside the ashram. On most of my previous visits I had stayed across the street in the Morvi guest house compound. He kindly granted my desire and accommodated me with a quiet room on the north side of the ashram, just at the foot of the holy Arunachala Mountain. Here, there are a line of rooms connected in motel-fashion and used by single men. My room was at the end of a group of six rooms.

Looking out my door to the north, sixty-year-old banyan trees lay out their branches and drop their swaying vines. These trees border the new ten-foot wall running east and west along the northern border of the ashram. Only one step beyond the wall the hill begins its 2600 foot ascent. As my room was at the end of the line of rooms, I had the good fortune of having a side, or west window. Looking out this window I could see straight into the door of the cottage built by A. Devaraja Mudaliar in 1940. Residing in this cottage, which is one of the older buildings of the ashram, is the oldest devotee of the Maharshi - Ramaswami Pillai at the age of ninety-seven. Gazing out my window into that room I usually would see this old, sturdy, resolute devotee sitting quietly in an easy chair.

He first came to Tiruvannamalai and visited the Maharshi as a teenager in 1911. After this, he attended college in Madras and settled down permanently with Bhagavan in 1922.

At the advanced age of ninety-seven, he is free from both mental and physical troubles. He can still walk a little, speak fluent English, and will at least once a day - usually during the middle of the night - burst out with recitations and songs composed by Bhagavan or in praise of him. His room is almost completely bare: not one book, no chest of clothes or paraphernalia. What he has gained by his seventy-year association with the Sage of Arunachala is secretly locked up in the interior of his heart chamber.

I would sometimes go and sit in his room. He would welcome me and readily speak of the efficacy of the practice of Self-enquiry. With short, direct and forceful sentences he would enliven my determination and fan the fire of devotion.

For about two weeks during my visit he was suffering from a bad cold. I would hear him coughing during the night and trying to sing with a gruff voice. Earlier, someone had given me a small quantity of ginger powder, mentioning that Bhagavan often prescribed it for colds. I passed this powder over to Ramaswami Pillai and asked him to use it in his tea or coffee. I told a friend of mine about Ramaswami Pillai's bad cold. This friend, who has known him for many years, went to his room and inquired about his health. In his old age, Ramaswami Pillai's hearing has faltered, so anyone speaking to him has to speak loud and clear. I heard the following 'loud and clear' conversation of my friend with Ramaswami Pillai:

Friend: How are you Swami?

R.P.: Oh, I am fine, by Sri Bhagavan's grace.

Friend: But your voice sounds like you have a cold or something.

R.P.: No. I am quite all right.

Friend: But Swami, someone told me you are having a bad cold and you are not well.

R.P.: Who told you that? I am quite fine! There is nothing wrong with me!

It must be this stubborn indifference to his body and physical wants that has resulted in his contentment, peace and long life. It was a stubborn determination that brought him here seventy years ago on the day of his marriage. His father had forced him into submitting to the marriage proposal, but he fled.

One day sitting beside him in his small room he turned and intently looked at me - mostly with his right eye, as the other is failing him - and asked, "Do you repeat it?"

Me: Repeat what?

R.P.: The Prayer. Do you constantly repeat it? You have to constantly repeat it.

Me: What prayer?

R.P.: Akshara Mana Malai, the 108 verses Bhagavan wrote on Arunachala. This itself is a powerful mantra.

He was not just talking theory to me that day. In earlier years I would hear him sing this Tamiḷ hymn over and over again for hours. And this, to the displeasure of some visitors and residents, would often go on in the middle of the night. But others within hearing range would welcome this nightly outpouring of devotion, taking it as a reminder that night and day we have to keep up the remembrance of God and abide in Him. Ramaswami Pillai occupies a permanent place in the history of Ramanasramam and the Maharshi's disciples.

The banyan trees near my room were the favourite haunt of the resident monkey tribe of Ramanasramam. The sprawling trees with their numerous hanging vines were the playground for the younger monkeys and the tangled boughs heavy laden with fresh green leaves served them all as a shady retreat from the hot afternoon sun. In town I had bought fried split peas and puffed rice, which I reserved for the monkeys and peacocks. Both of these, being quite aware of this cache, would regularly appear at my door. Two peacocks would daily visit and produce a loud honk, announcing their presence. The monkeys, some with infants clinging to their stomachs, would whine or shake the screen door.

Every morning after breakfast I would stroll over and visit the goshala (the cow shed), which has expanded considerably over the last few years. Seventy head of cattle occupy a couple acres of land: the new calves in the goshala building, yearlings and heifers in two open, fenced-in pens attached to shelters, and mother cows occupying other stables, all spotlessly clean and efficiently maintained. I am sure Bhagavan would have taken great delight to see it. (But how can I say that he is not taking delight even now?) I soon became intimate with several of the mother cows and calves. They would eagerly move toward me - as much as their tethers allowed - when I came. It wasn't just the few small lumps of brown sugar I saved from my breakfast that they were after. Since we kept cows at the Nova Scotia ashram for ten years, I was quite familiar with all those special spots around their head and back which are most welcomed to be rubbed and scratched. I had watched Bhagavan stroking the cows in these very same places on the ashram archival films.

The ashram has, with government assistance, installed a large bio-gas plant. Daily, fresh manure is put into it and the gases produced are piped into the kitchen and dining hall, providing fuel for cooking and emergency lighting. The used manure that flows out of the tank is later applied to the numerous trees (now sixty varieties!), shrubs and flowers as fertiliser. Over the last seven years the ashram has been transformed into a virtual garden with flowering vines, trees, potted plants, grasses and shrubs everywhere you look. The ashram management, V. Subramanian in particular, has taken keen interest in developing the ashram grounds in an ecologically sound and aesthetic manner.

Silence

Maharshi: Language is only a medium for communicating one's thoughts to another. It is called in only after thoughts arise; other thoughts arise after the 'I'-thought rises; the 'I'-thought is the root of all conversation. When one remains without thinking one understands another by means of the universal language of silence.

Silence is ever speaking; it is a perennial flow of language; it is interrupted by speaking. These words obstruct that mute language. There is electricity flowing in the wire. With resistance to its passage, it glows as a lamp or revolves as a fan. In the wire it remains as electric energy. Similarly also, silence is the eternal flow of language, obstructed by words.

What one fails to know by conversation extending to several years can be known in a trice in Silence, or in front of Silence, as was the case with Dakshinamurti and his four disciples.

Living with the Master

In our last issue we read how Chhaganlal Yogi, the sceptic, became a believer, and how the Maharshi showed him in a dream to whom he should sell his business, and for what price. As the story continues, we now read how he is led into a different business: printing for Sri Ramanasramam.

My original plan had been to sell all my property in Bombay and move directly to Sri Ramanasramam. However, when the devotees heard what I was planning to do, it was suggested to me that I could be of more use to the ashram in Bangalore. I was asked to start a printing press there which could execute all of Sri Ramanasramam's printing work. I agreed to the idea and soon found myself in Bangalore, looking for suitable premises. I began to suspect that Sri Bhagavan had assisted the sale of my original press because he had work for me to do in Bangalore.

I was a stranger in the city but I soon located an old press which had been lying idle for the previous six months. It was for sale. I saw its proprietor and told him why I wished to buy his business. He agreed to sell it to me but we were unable to agree on a price. To break the deadlock I proposed that both of us should visit the ashram and suggested that we could talk about the deal after we had had Sri Bhagavan's darshan. I thought that since Sri Bhagavan wanted me to do this work in Bangalore, his darshan might help to lubricate the wheels of the transaction.

The owner agreed to the idea, so we set off together for Sri Ramanasramam. On arrival, I took him into the holy presence of Sri Bhagavan and informed him that I proposed to buy the press of the gentleman who was accompanying me, and that I planned to do all the ashram's printing work there. Sri Bhagavan did not say anything; he just nodded his head.

Within a few hours of having had Sri Bhagavan's darshan, there was a wonderful change in the attitude of the owner of the press. He approached me and agreed to sell his press for whatever price I was willing to pay for it. I stated a reasonable amount since I did not want to exploit him, and he happily accepted my offer. When he had agreed to come and see Sri Bhagavan with me he had made a stipulation that no business talks should take place at the ashram. However, after seeing Sri Bhagavan, he proposed that we settle our business immediately. We drafted and signed a sale agreement in the ashram itself and within a week of our visit the press came into my possession.

It was a fairly big press which enabled me to do all kinds of printing work in several languages. Because of the good facilities that were available there, I undertook to print ashram books in English, Tamiḷ, Hindi, Gujerati and Kannada.

The press, which was given the name 'Aruna Press' by Sri Bhagavan, had been idle for six months. It needed a lot of work to get it functioning again, but by Sri Bhagavan's grace I was soon able to take up the ashram work that had been given to me.

In 1946, the devotees of Sri Bhagavan decided to celebrate a golden jubilee to commemorate Sri Bhagavan's fifty years at Arunachala. He had arrived on September 1, 1896, and on that same date in 1946 the ashram proposed to mark the occasion by a number of special events, one of which was the publication of a book entitled The Golden Jubilee Souvenir. The printing of this souvenir was entrusted to my press. Up till then, the press had only printed small books for the ashram. Since this was going to be a big volume of several hundred pages, I was initially reluctant to accept the work because I felt that I would not have enough time to complete it. However, once I overcame my diffidence and accepted the commission, help and co-operation began to pour in. Since some of it was wholly unexpected, I suspected that Sri Bhagavan's divine grace was again at work.

At first, my initial fears appeared to be justified. When only ten days remained before the publication date, I had still not managed to print more than a small part of the book. I temporarily lost my courage and rushed off to the ashram. I prostrated before Sri Bhagavan, told him about the lack of progress and informed him that unless the help of some other press is taken, the volume will not come out on the first of September.

I sat before him enjoying his darshan waiting for his reply. After a few moments of silence he said in a low melodious tone, "Do your work."

These three simple words had a magical effect on me. They fired me with fresh vim and vigour and there arose in my heart a strong belief that the volume would surely be out on the scheduled date. I had received my orders from my Master. I had simply to obey and "do my work". I had faith that all the other details would be looked after by him.

I returned to Bangalore and told the story of my experience at Sri Ramanasramam to my co-workers in the press. All of them accepted Sri Bhagavan's order in the same spirit as I had done. For the next few days all of us worked day and night with full faith, zeal and enthusiasm. The amount of work turned out in those last ten days was, in retrospect, quite astonishing. Then, when three days remained till our deadline, a party of about ten devotees came to my house on its way to the ashram. They were going there to attend the golden jubilee celebrations. Three of them turned out to be expert book-binders. I immediately enlisted their aid and managed to complete the work of the souvenir a day early.

Between 1945 and 1947 the Aruna Press printed all the publications of Sri Ramanasramam. The work was complex and I often found myself having to argue with the official at Sri Ramanasramam who had been put in charge of the publications. The tension between us increased to the point where both of us decided that we should go to Sri Bhagavan to get our differences resolved.

The rest interval between noon and 2:30 p.m. was chosen for our meeting because we wanted to be alone with him. We went to the hall at noon and waited outside for him to return from lunch. On his way back he saw both of us waiting for him. Sensing that we had some business to discuss, he took his seat on the big stone couch outside the hall. My friend immediately started to present his side of the dispute. However, it soon occurred to him that Sri Bhagavan was not comfortable sitting outside on this stone bench. He stopped in the middle of his plea, folded his hands in a respectful way, and requested Sri Bhagavan to go inside the hall. He said that the business should be conducted with Sri Bhagavan seated comfortably on his sofa.

Sri Bhagavan dismissed the appeal with a smile, saying, "What is wrong with the seat? Was there a soft bed and sofa when I was up there (pointing to the hill)? Up there the bare stones served as my bed as well as my seat."

It was clear that in our unseemly haste and our anxiety to plead our respective cases we had been responsible for causing this discomfort to him. Feeling very guilty about this, I felt very embarrassed when my friend's request was turned down. In an anguished voice I begged Sri Bhagavan to follow the advice.

"No, Bhagavan, no. That won't do," I said. "It is our earnest prayer that you should not sit here in the hot sun. We will resume our talk only after you go into the hall and sit comfortably on the sofa."

This time he accepted the advice. He got up, went inside and, as requested, sat on his sofa. Both of us then placed our cases before him. He quietly listened to us and gave his verdict in the language of silence. Smiling with great charm he maintained complete silence, both during and after the presentation of the arguments. The judgement was the best possible one for both of us. Sri Bhagavan's silence had healed the breach. As we emerged from the hall both of us had a spontaneous impulse to embrace the other. In those few minutes our hearts had changed. We separated with the resolve to bury the past and to treat each other in the future with love and friendship. The silken tie with which Sri Bhagavan bound us on that day has never snapped again.

Sometimes in life there is a clash between two competing obligations, especially if both seem to be equally important. At such times it is rather difficult to arrive at the right decision. It has been my experience that at such times our gracious Master leads us to the proper decision. I will give an example from my own life.

At one time I felt that my political duty as a Gandhian demanded that I should court arrest, but my domestic duties bade me otherwise. As I was eager to go to jail as part of the independence struggle, it pained me that, out of regard for my family, I was not able to do so. I found myself in a dilemma and I could not of my own accord see the way out. The situation was so unbearable for me that I had to turn to the Master for help and relief. I therefore set out for Tiruvannamalai.

After reaching there I went and sat in the holy presence of the Master. While I was sitting there I began to wonder how I should place my difficulty before him because I did not feel like broaching the subject verbally. I finally decided to pour forth my prayer from my heart in silence in the form of a plea for Sri Bhagavan to extend his benign help to me. I began to pray and while I concentrated on my mental plea I watched his radiant face and his sparkling eyes, which were full of love and kindness. And then, astonishingly, something like a miracle began to happen. Sri Bhagavan's face transformed itself into that of Mahatma Gandhi, while his body remained the same. As I stared at it with awe and wonder, the two faces, those of Sri Bhagavan and Gandhiji, began to appear to me alternately in quick succession. I felt my heart filling with joy and yet at the same time I was wondering whether what I saw was real or not. I turned my eyes away from Sri Bhagavan and looked around me to see if others were seeing what I saw. Seeing no sign of wonder on their faces, I concluded that what I saw was a picture from my own imagination. I closed my eyes and sat quietly for some time. Then, as I began again to look at Sri Bhagavan's face, the vision immediately reappeared, but this time with a slight change. In addition to the two faces of Sri Bhagavan and Gandhiji, those of Krishna, Buddha, Kabir, Ramdas and a host of other saints began to show themselves in quick succession. Now all my doubts vanished and I began to enjoy this grand and divine show. The vision lasted about five minutes. My mind dropped all its worries and I found myself able to hand over my problem to the capable hands of the Master. Though he spoke no words to me, it came to pass that the problem was solved without infringing either of my two duties. In fact, both duties were fulfilled satisfactorily.

I had another vision of Sri Bhagavan in 1943. During my visit to Sri Ramanasramam that year, I visited the temple of Sri Arunachaleswara with my family and a friend who was a devotee from Madurai. This is the main temple in Tiruvannamalai, the same one which Sri Bhagavan stayed in when he first arrived here.

While we were walking through the spacious courtyards towards the sanctum sanctorum, I did not have any inkling of the wonderful experience I was to pass through when I finally saw the deity.

On reaching the innermost shrine we discovered that we were early, for the doors of the shrine had not been opened. We decided to wait there till someone came to unlock them. I leaned back against a pillar and began to think about Bhagavan's early life. Suddenly my thoughts started to materialise physically as scenes from his early life began to appear before my eyes as vividly as if I were watching a cinema film.

I saw very clearly Venkataraman writing the imposition in his uncle's house in Madurai. Leaving it aside, he sits bolt upright, closes his eyes and becomes absorbed in the more congenial practice of Self-absorption. His elder brother Nagaswami is watching him and rebukes him for neglecting his lessons. Venkataraman then decides to leave the house. He takes three rupees from his brother's college fees and departs after leaving a short note. He reaches the railway station. He buys a ticket to Tindivanam, gets into the train and sits quietly in one corner. A moulvi who is discoursing to other passengers notices him and asks him where he is going . . . . Scene by scene, I was enjoying this wonderful divine vision when the doors of the shrine opened and my vision was interrupted by the loud blowing of pipes and beating of drums. The people who were waiting with us stood up to get the Lord's darshan. I too mechanically stood up with the others. After this short interruption, my vision continued. Though the idol of Sri Arunachaleswara was before my eyes, I could clearly see Venkataraman getting out of the train at the Tiruvannamalai station. He then ran towards the temple. As he was coming nearer and nearer, the noisy music rose to a higher and higher pitch. Venkataraman entered the temple, ran to the shrine and embraced the lingam with both his hands. My feelings were ecstatic. My whole body experienced a divine thrill and tears of joy rolled down my cheeks. This state of sublime joy lasted a long time and was both indescribable and unforgettable.