Living with the Master - Part III

by Chhaganlal Yogi

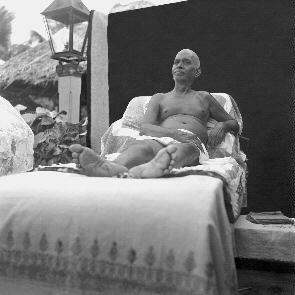

For most of the day Sri Bhagavan used to sit on his sofa, which was adjacent to a window. Squirrels would occasionally come in through the window and run around near him. Sri Bhagavan would often respond to them by lovingly feeding them cashews or other foodstuffs with his own hand.

One day Sri Bhagavan was feeding the squirrels when a Muslim devotee, who had been watching him, gave him a note in which was written: "The squirrels are very fortunate because they are getting the food from your own hands. Your grace is so much on them. We feel jealous of the squirrels and feel that we also should have been born as squirrels. Then it would have been very good for us."

Sri Bhagavan couldn't help laughing when he read this note. He told the man, "How do you know that the grace is not there on you also?" And then, to illustrate his point, he started to tell a long story.

"One saint had the siddhi of correct predictive speech. This is, whatever he said came true. In whatever town he went to, the local people would come to him to have his darshan and to get his blessings. The saint, who was also full of compassion, removed the unhappiness of the people by blessing them. Because his words always came true, the blessings always bore fruit. That is why he was so popular.

"During his wanderings he came to a town where, as usual, a lot of people flocked to him to get his blessings. Among the blessing seekers there was a thief. He went to have darshan of the saint in the evening and asked for his blessings. When the saint blessed him, the thief was very happy. He felt certain that because of these blessings, when he went out to steal at night, he would be successful. But it turned out otherwise. Whenever he went to break into a house, somebody or other from that house would wake up and he would have to run away. He tried in three or four places but he could not succeed anywhere.

"Because of his failure, the thief got very angry with the saint. Early the next morning he went back to him and angrily said, 'You are an impostor! You are giving false blessings to the people.'

"The saint very peacefully asked the reason for his anger. In reply the thief narrated in detail how unsuccessful he had been during his attempts to steal the previous night. Having heard his story, the saint commented, 'In that case, the blessings have borne fruit.'

"How?" the thief asked with astonishment.

"Brother, first tell me, being a thief, is it a good or a bad job?"

"It is bad," the thief admitted, but then he defended himself by saying, "but what about the stomach that I have to feed?"

The saint continued with his explanation: "To be unsuccessful in bad work means that the blessings have indeed borne fruit. There are so many other ways of feeding the stomach. You should accept any one of them. To come to this conclusion it was necessary that you be unsuccessful in your thieving work."

"The thief understood and informed the saint that in future he would take up some other honest work. He prostrated before the saint and left."

Having narrated the above story, Sri Bhagavan asked the Muslim devotee, "Do you mean to say that if everything goes according to your desires, only then is it possible to say that the grace of a saint has worked?"

"I don't understand," replied the Muslim.

Sri Bhagavan explained in more detail: "The blessings of a saint perform the purificatory work of life. These blessings cannot increase impurity. One whose understanding is limited will ask for blessings so that he can fulfill certain desires, but if the desires are such that their fulfillment will make the seeker more impure rather than purer, the saint's blessings will not enable him to fulfill the desires. In this way the seeker is saved from further impurities. In that case, are not the saint's blessings a gift of compassion?" The Muslim finally understood and was satisfied by these words.

As Sri Bhagavan's fame began to spread, the number of visitors to the ashram increased. Many of them tried to offer him presents such as fancy sheets for his sofa, curtains for the doors and windows, embroidered carpets, etc. In order to satisfy the devotees who offered these things, Sri Bhagavan would usually allow his attendant to substitute for a short period of time the new offerings for the ones which were already in use. After a few hours they would be removed and sent away to the ashram storeroom, and the old, still-serviceable items would be brought back into use. Sri Bhagavan would briefly utilize these presents merely to strengthen the devotion of the donors. Left to himself, he would use cheap or old items, and never claim that they were his own. Devotees who tried to get him to use newer or better-made products could always count on resistance from Sri Bhagavan himself. I discovered this for myself when I tried to give him a new pen.

Sri Bhagavan generally used two fountain pens: one contained blue ink, the other, red. Both of these pens were quite old and looked, to me at least, worn out. One day the top cover of the red-ink pen cracked, so a devotee took it to town to have it repaired. It was gone for several days. During this period Sri Bhagavan reverted to an old-fashioned nib pen which had to be dipped in an ink pot of red ink. Since this seemed to cause him some inconvenience, I decided to get him a new pen. I wrote to a friend in Bombay and asked him to send one immediately. A few days later the pen arrived by post. I went straight to Sri Bhagavan and handed over the unopened parcel containing the pen.

Whenever a parcel or letter bore the name of the sender on the cover, Sri Bhagavan never failed to notice it. As soon as he received the packet from me, he turned it over and read the name of both the recipient and the sender. Having deduced that the parcel had been sent at my instigation, he took out the pen, carefully examined it, and put it back in the box. He then tried to hand the box to me.

Allowing it to remain in his hand, I explained, "It has been ordered from Bombay especially for Sri Bhagavan's use."

"By whom?" he asked.

"By me," I said, not without some embarrassment because I was beginning to feel that Sri Bhagavan did not approve of my action.

"What for?" demanded Sri Bhagavan.

"Sri Bhagavan's red-ink pen was out of order," I said, "and I saw that it was inconvenient to write with the nib pen."

"But what is wrong with this old pen?" he asked, taking out the old red-ink pen which had by then been received back in good repair. "What is wrong with it?" he repeated. He opened it up and wrote a few words to demonstrate that it had been restored to full working order. "Who asked you to send for a new pen?" demanded Sri Bhagavan again. He was clearly annoyed that I had done this on his behalf.

"No one asked me," I said, with faltering courage. "I sent for it on my own authority."

Sri Bhagavan waved the old pen at me. "As you can see, the old pen has been repaired and writes very well. Where is the need for a new pen?"

Since I could not argue with him, I resorted to pleading and said, "I admit that it was my mistake, but now that it has come, why not use it anyway?" My plea was turned down and the new pen went the way of all its forerunners: It was sent to the office to be used there.

Sri Bhagavan gave us an example of how to live simply by refusing to accumulate unnecessary things around him. He also refused to let anyone do any fund-raising on behalf of the ashram. In this too he set an example. He taught us that if we maintain an inner silence and have faith in God's providence, everything we need will come to us automatically. He demonstrated the practicality of this approach by refusing to let anyone collect money for the construction of the temple over his mother's samadhi. Though large amounts of money were being spent on it every day, we had to rely on unsolicited donations to carry on the work. I knew this from direct experience because one day the ashram manager asked me to get permission from Sri Bhagavan to go to Ahmadabad to ask for a donation from a rich man I knew who lived there. Sri Bhagavan, as usual, flatly refused. No amount of persuasion could move him from his categorical "No."

"How is it," he complained, "that you people have no faith?" He pointed to the hill and told us, "This Arunachala gives us everything we want."

In his early years on the hill Sri Bhagavan and his devotees lived on begged food. He had no objection to this form of begging. Indeed, as a teenager he had walked the streets of Tiruvannamalai, begging for his own food. What he objected to, when devotees went out to beg for their food, was asking for specific items. Devotees could only eat what was freely given.

In the period that Sri Bhagavan lived in Virupaksha Cave, visiting devotees would often leave food for the people who lived there. The resident devotees would beg for additional food if the donated food was not enough. If the combined total was insufficient to make a good meal for everyone, Sri Bhagavan would mix all the food together, add hot water and make a kind of porridge which would then be shared equally among all those present.

Devotees who found this homemade gruel unappetizing would sometimes request that at least some salt should be added to the mixture.

"But where are we to get the salt?" Sri Bhagavan would ask. "Who will give us salt unless we specifically ask for it? If once we relax our rule of non-begging in order to get salt, the palate that craves for salt today will next cry out for sambar, then for rasam, then for buttermilk and so on. Its cravings will thus grow endlessly. Because of this we should stick to our rule of non-begging."

It was certainly no joke to live with Sri Bhagavan in those early days. Sometimes the devotees had to do without salt, at other times without a substantial meal. There were even days when there was no food at all.

When Sri Bhagavan's mother came to stay with him she insisted on starting a kitchen. Utensils were needed for it, but how to get them without asking or making the need known? Some things were acquired easily. When the word spread that a kitchen had been started, many of the necessary items of equipment arrived unasked from devotees who lived in town, but some useful utensils were not forthcoming.

Sri Bhagavan's mother solved the problem merely by bringing it to his attention. It was well known that if Sri Bhagavan suddenly became aware that some needed item was not available in the ashram, it would often appear, unasked, soon afterwards. This happened far too often for it to be a coincidence.

One day, for example, a ladle was required. Instead of asking for it from some devotee, his mother told Sri Bhagavan about it. He merely replied "We'll see," but he didn't ask anyone to bring one. How could he, who had taken to non-begging, ask even for a ladle? But within a couple of days a devotee, of his own accord, brought half a dozen ladles and placed them at his mother's feet. When other vessels or utensils were needed, she would inform Sri Bhagavan and he would give his usual reply: "We'll see." Within a short space of time the required item would arrive. So, without breaking or relaxing Sri Bhagavan's strict 'no specific begging' rule, the kitchen at Skandashram expanded and thrived.

This did not only happen with kitchen items. During his stay at Virupaksha Cave Sri Bhagavan often developed a severe cough. During one of these attacks he took a bala harade (a small myrobalan or cherry plum) as a remedy, chewing it and swallowing its juice. This treatment lasted for a considerable amount of time, as a result of which the entire ashram stock of bala harade was consumed. When there were none left, the cough returned with more violence and vigor. Palaniswami, Sri Bhagavan's attendant, asked for permission to buy more bala harade from the town. Of course, the permission was not granted.

A few minutes later Sri Bhagavan casually remarked, "Harade (big myrobalan) is a better remedy than bala harade for coughing." Shortly afterwards a devotee entered the cave with a small bundle in his hand. He had come to pay homage to Sri Bhagavan.

Holding the bundle before him he said, "As I was coming here from my village, I saw a man sitting on the roadside selling big myrobalans. It struck me that it was good for coughing, so I brought some for Sri Bhagavan's use."

He opened the bundle and placed it before Sri Bhagavan, who asked him with a smile on his face, "But why did you buy so much?" The devotee replied, "It was quite cheap and the seller wouldn't agree to sell me a small amount. I had to buy all of them. Let them be here. Since I don't want any myself, let them stay here.

The idea of buying and bringing harade to the ashram thus coincided with the utterance of Sri Bhagavan's words. Can this coincidence be attributed to anything else than his strict observance of the rule of non-begging?"

At times, also to cure his cough, Sri Bhagavan used to chew black raisins.

These also ran out while Sri Bhagavan was still having coughing attacks. Palaniswami again requested Sri Bhagavan to allow him to buy more from the town, but his request was summarily turned down with the remark, "Let's see. Where's the hurry?"

A few minutes later Sri Gambhiram Seshayya entered with a packet in his hand. "What have you brought?" someone asked.

"Raisins," was the reply.

"Then you must have known about our talk here," said Sri Bhagavan with a laugh.

"No Bhagavan!" said Sri Gambhiram, folding his hands in namaskar, "How could I know in advance what was being talked about here? It just occurred to me when I started out from my house that I should bring something to offer here. When I went to the market, only one shop was open. In that shop only a small quantity of black raisins was available. There was nothing else there which could be useful here. So, I had to buy these black raisins. The thought of buying them never occurred to me before I entered the shop."

If there is a moral in these stories it is that all things flow towards the person who adheres strictly to the resolve of non-begging. Or, one could say that if one abides as the Self with the conviction that there is a Higher Power which arranges for all the necessary things to be supplied, then one need not go looking for them because they will arrive unasked.

Returning to Ramanasramam - Part II

by Dennis J. Hartel

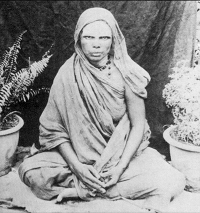

"She was one of the luminaries that revolved around the sun, which Sri Bhagavan is for the world," said K.Venkataraman, popularly known in Sri Ramanasramam as K. V. Mama. He was telling me about someone he knew intimately, so intimately that he had always called her mother, even though she wasn't his mother. She was his grandmother, and Echammal was her name.

Anyone who has ever read about the string of tragedies that befell Echammal before she came to the Maharshi can only remotely imagine her grief. Think of it: you are happily married and well placed at the age of twenty-four; blessed with two lovely children, one girl, one boy; your husband falls ill and within a short time dies; before you are able to recover your mental balance from this loss, your son falls ill and dies; and even while you are still in a state of shock, your dearly loved daughter, your sole remaining child, is also taken away in the same manner. If you have a family, think about it . . . . What would be your condition after such a series of tragedies within a lapse of less than one year?

Yes, that was Echammal's condition when she walked up to the Virupaksha Cave to meet the young sage, then called Brahmana Swami. She stood before him for one hour, and in that one hour her tormented heart and shocked mind were transformed. A wave of peace gently rolled into her heart and the dark cloud of anguish dispersed from her mind. K. V. Mama joyfully recalls this event as if it was his own birth. And, in a way, it was.

After this meeting with the Maharshi, Echammal settled down at Tiruvannamalai in 1907. Subsequently, her niece, who Echammal adopted, came to live with her. Chellammal was her name and, like Echammal, she looked upon the Maharshi as her Saviour and Lord. In K. V. Mama's words:

"Chellamma was a ripe soul, recognized by Echammal, and completely surrendered to Bhagavan." Chellamma was K. V. Mama's mother.

Added to the list of Echammal's tragedies was the death of Chellamma soon after she had given birth to her first child. The Mother's dying wish was that her boy should be raised by Echammal. That is why K. V. Mama doesn't remember calling anyone by the name of mother other than Echammal.

While I was in Ramanasramam I began re-reading about Echammal's life. She was perhaps the most prominent woman devotee of the Maharshi, serving him and his devotees for nearly forty years. I looked through all the ashram publications and found that there wasn't much printed about her. From the few anecdotes I read, it became clear that her real, or complete, story is yet untold, and there was no one more qualified to tell it than K. V. Mama. Ten years ago K. V. Mama retired from government service, and since then he is regularly seen working in the ashram office, serving the needs of devotees and guests.

I had read that Echammal, after meeting Bhagavan, returned to her village, collected all her belongings, came back to Tiruvannamalai and rented a house in town. "Where was that house?" I asked K. V. Mama. Bubbling over with enthusiasm and love, he said, "It is at 42 Car Street, near the eastern gate of the Arunachala Temple. I will take you there." Then he went on to explain: "At the time she settled here, Bhagavan was coming down the hill to beg his food. She then got the idea that there was no need for Bhagavan to make this trip into town to beg his food, as she was prepared to take cooked food up to him every day. Thus began her daily food offering to Bhagavan that continued uninterruptedly until her death thirty-eight years later.

"Echammal used all her resources to serve Bhagavan and his devotees. When Bhagavan's mother came to spend her last years with her son on the hill, the devotees staying with Bhagavan didn't agree with the idea of having a woman living in the ashram, even if that woman was the Maharshi's mother. Bhagavan was then living in Virupaksha Cave.

"Echammal took Alagammal (Bhagavan's mother) to live with her in town. For one week Alagammal and Echammal walked up the hill every day to see Bhagavan. Although Alagammal would live seven more years, her health was not robust and the daily climb up to Virupaksha Cave was wearing her down. Seeing this, Echammal took up Alagammal's case before Bhagavan and his devotees. She told them that it wasn't right to make Mother suffer in this way, as she had left everything and had come to take refuge in her son; "and yet you will not permit her to stay with him," she said.

"Bhagavan's disciples countered her arguments, saying that if they allowed the Mother to stay, next Echammal and other woman devotees would be demanding the right to stay also. 'Then what kind of ashram will this be?' they asked.

"Echammal then told them, 'Can I, or any other person on earth, be as blessed and fortunate as the Mother of Bhagavan? She cannot be looked upon as an ordinary woman. Right here, standing before Bhagavan, I make the pledge that I will never request to stay in the ashram, nor will I ever ask permission for any other woman to stay in the ashram.' Even after hearing all of this from Echammal, Bhagavan's disciples still refused to relent to her request.

"Throughout this whole discussion Bhagavan remained silent. His silence was interpreted by the men devotees to mean that he agreed with them and didn't support Echammal's view. But, after Bhagavan heard Echammal's appeal, he quietly rose and walked over to his mother, took her hand in his, and said, 'Let us go. We can find some other place to stay. They do not want us here.'

"Of course, all the men devotees immediately withdrew their objections and Mother was accepted into the ashram. Thus Echammal played an important role for securing the comfort of Bhagavan's constant company for Alagammal in the final years of her life."

K. V. Mama took me by auto rickshaw to the house where he lived with Echammal at 42 Car Street. He knows the present owners intimately, as they are the descendants of those who lived there when he was a boy. With evident glee he showed me the rooms throughout the large complex: "This is were Echammal slept . . . where she cooked for Bhagavan . . . the well she drew water from . . . ." In this manner he went on telling many stories, remembering how Ganapati Muni, Seshadri Swami and others would come to this house to take food from Echammal. With joy and affection he narrated whatever he could remember. One could not mistake how at the center of his life, his mother's life, and Echammal's life, Bhagavan was the guiding force and source of inspiration. Like the links of a chain, these three generations have been united and locked together in the love of their Lord, Ramana. Bhagavan seemed as much present now for K. V. Mama, as when he was a boy riding on the bullock cart taking food to Bhagavan with Echammal. Before leaving I took photos of the house wherever I could find adequate lighting.

I later asked K. V. Mama about the death of Echammal. He related some events not recorded in any of the ashram books. It seems that, though Echammal was not suffering from any illness, about two weeks before her death she travelled to Madras and asked one of her nephews if he would conduct the obligatory ceremonies upon her death. She even discussed the matter with Bhagavan at this time. Surely she must have felt a premonition. Bhagavan was told by several devotees how Echammal lapsed into unconsciousness two days prior to her death. In spite of this, when Bhagavan was question whether she was conscious at her death, he said, "Yes, she was. She remained as in samadhi and passed away. It is even said they did not know when exactly life expired." This was recorded in Day by Day with Bhagavan.

When I had heard so much about Echammal from K. V. Mama, I began wondering about her ashes, which I understood to be buried in her village. I asked K.V.Mama how far away was her village and if there was a monument at her grave site. K. V. Mama sadly confessed that the land where her ashes were buried was sold long ago by her brother. Also, he was uncertain about the fate of the ashes. Then I said, "Shouldn't her ashes be brought here and buried near her Master? Who will remember her in the village? She will always be remembered here. Can't we go dig up those ashes, bring them here, and place a small memorial over them?" K. V. Mama was immediately enthused by the idea. Already he had constructed a two storey cottage in the ashram in memory of Echammal. Returning her physical remains to the place where her whole life was centered, certainly would be the final consummation of her devotion and dedication.

Two days later I walked into the ashram office and saw K. V. Mama quietly sitting at his desk. When I looked closer at his face I saw a teeming excitement bristling just below the surface. I sat next to him and asked him if he had any news. He warmly took hold of my left hand and clapped my palm saying, "Kumar, my son, and his family are coming here from Bangalore tomorrow. He will do pradakshina and leave on Sunday. Before he leaves I want him to take us in his car to Valapakkam, Echammal's village."

On Sunday morning, September 31, 1993, at 6 a.m. I was in the ashram kitchen drinking coffee, while K. V. Mama packed iddlies into his tiffin carrier. J.Jayaraman, the ashram librarian, was also accompanying us on the trip. Kumar arrived and we joined him. We first drove around the holy hill and then joined the Vellore road, driving north. It was thirty miles to Valapakkam and it took us about one hour to reach there.

It had been twenty years since K. V. Mama had visited Echammal's village, and his son, Kumar, last saw the place when he was eight. Echammal's nephew, who now resides in the ancestral home, is 90-years-old. He and all the household were surprised and happy to see K. V. Mama and his son. The old man of the house was still quite alert and could speak both Tamiḷ and English. He, in fact, is K. V. Mama's uncle, being the brother of his mother, Chellammal. He remembered Echammal very well. His daughter brought out an ochre-colored sari that belonged to Echammal which they were preserving. I asked for a piece of the cloth to keep as a relic in memory of her. They gladly ripped a strip from its hem and handed it over to me. We inquired about Echammal's ashes. K. V. Mama's uncle said he also was interested in digging them up a few years back. The land where they had been buried was sold in 1956. In 1957 his father went on a pilgrimage to north India, and only recently he was told that when his father visited Varanasi he scattered the ashes of his cherished daughter (Echammal) over the holy waters of the Ganga. That meant the ashes were gone.

Nevertheless, we decided to take a ten minute walk through the fields and farmlands to the site where her ashes were once buried. Standing there and looking south at the horizon, a slim outline of a solitary, symmetrical hill can be seen. It is Arunachala, the holy hill that drew this grieving mother, Echammal, to His divine son, Ramana. And as long as the son, or "the sun, which Sri Bhagavan is for the world" is remembered, Echammal will be remembered.