h1 id="article.1" class="ctr">The Recollections of N. Balarama Reddy

Part V

Bhagavan's Love and Care

It is hard to describe, and it was a wonder to see, how Bhagavan bound all with his love. Between Bhagavan and some of his long-standing devotees words would never pass. Nevertheless, these devotees, whether men, women or children, knew that Bhagavan's love and grace was being showered on them. By a single glance, a nod of the head, or perhaps by a simple inquiry from Bhagavan - sometimes not even directly but through a second person - the devotees knew that he was their very own and he cared for them. In his presence all distinctions and differences were resolved. We lived together like a huge family with Bhagavan at the center, guiding us and shedding his grace and blessings on all.

Bhagavan was most considerate and kind-hearted, but at the same time he was a strict disciplinarian. Even if he appeared indifferent to the onlookers, he still took a keen interest in the progress of seekers, particularly if they happened to be youngsters. Many times I was helped by Bhagavan.

Later, for instance, due to a crisis in my home, I was informed that my continuous presence in the village was now required. That meant I would have to leave Bhagavan for good. When I received this news I went and explained it all to Bhagavan, who kindly listened and then simply nodded his head. The meaning of this nod I understood only upon receiving a letter from my mother, who wrote that I need not leave the presence of Bhagavan and that she would attend to all the affairs in the village. This was a turning point in my worldly life and it was due, no doubt, to the direct intervention of Sri Bhagavan's Grace. When I showed my mother's letter to Bhagavan, he read it and gave me a benign smile, as if to say: "Are you now satisfied?"

It was a mystery to see how he was so detached from the ashram and its operation, but yet was still somehow getting everything done as he wished. The Sarvadhikari, Sri Niranjanananda Swami, once told me, "It is difficult for others to understand, but sometimes I feel there is something like a wireless connection between me and Bhagavan."

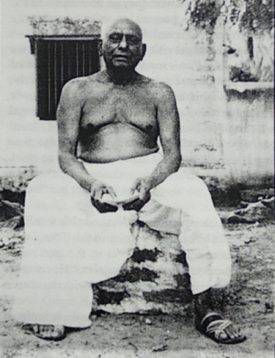

Niranjananda Swami

Bhagavan's brother had to endure considerable criticism while managing the ashram. Even so, there is little doubt that Bhagavan used him as his instrument. When Niranjanananda Swami felt an inner prompting from Bhagavan, he confidently acted on it. The following may be an example of one such occasion.

It is widely known that Paul Brunton's book, A Search in Secret India, did much to make known to the world that the Maharshi, a unique sage of this century, was living inTiruvannamalai. Brunton was a professional writer and in those days wherever he would go he would often be seen taking notes on bits of paper. While in the Old Hall listening to questions put to Bhagavan and his replies, he would be eagerly taking notes. After the success of A Search in Secret India, he began writing many other books in which he would sometimes adopt the Maharshi's teachings without giving due acknowledgment. When the ashram authorities realized this they decided to stop him from taking notes in the hall.

One day in 1939, Brunton was sitting next to me taking notes as usual when Niranjanananda Swami boldly walked into the hall, stood next to Bhagavan and told Munagala Venkataramiah to tell Brunton in English that he is no longer permitted to take notes while sitting before Bhagavan. Brunton was told accordingly. Brunton looked at Venkataramiah and said, 'Is this also Bhagavan's view ?' Venkataramiah did not reply to this question and Bhagavan who was quietly sitting there didn't say a word either. A few tense moments passed. Then Brunton stood up and left the hall. That was the last time he took notes in the hall, and that was also when Brunton began distancing himself from the ashram.

It was very unusual to see the Sarvadhikari appear so bold and authoritative before the Maharshi. He must have felt that this exploitation should stop and was confident that Bhagavan was behind him.

Correcting Proofs and Settling in the Ashram

It was perhaps a year or two later, when I was preparing to make a trip back to my village, when Bhagavan asked me to check through the proofs of the fourth edition of Self Realization, written by B.V.Narasimha Swami. I was in the hall and getting ready to take leave of Bhagavan when the final proofs - we called them "strike forms" back then - for the fourth edition of Self Realization were handed over to Bhagavan. He called me, handed over the proofs and requested me to go through them. I thought it odd that although Bhagavan knew I was planning to leave that day, he would detain me with some work. It is said in the scriptures that the guru blesses his sishyas (disciples) by giving them work to do, and so I naturally felt blessed at his request, especially because he would rarely ask any one of us to do anything for him.

When I had gone through one proof, another would arrive, and in this way my trip home kept getting delayed. When I had finally finished all the strike forms and showed Bhagavan the errors, he expressed surprise and said, "I have gone through these proofs, others have gone through them, and after all of this Balarama Reddy finds more errors!" The corrections I found had to be added in the end of the book under the title 'ERRATA.'

Completing this work, I returned to my village for the summer months. While I was there the newly-printed fourth edition of Self Realization arrived at my house by post. The book was inscribed: 'With the blessings of Sri Bhagavan.'

Perhaps Bhagavan had reminded the office that I had worked on the proofs and requested them to send me the new release. I have preserved that book in my village.

When I returned at the end of the summer, the ashram administration, for some reason, made a change in their policy regarding my residence in the ashram. It was my regular practice to stay a few days in the ashram and then settle into some rented room in town. This time the management favored me by letting me remain in the ashram itself. I placed my things in the northeast corner of the Guest House for Gentlemen. The ashram kindly gave me a very large, thick Malaysian mat, woven with split bamboo, to spread on the floor. I hung carpets on the west and south sides and thus created my own simple room, which I found quite comfortable. I believe I may have been at that time the only devotee allowed to live in the ashram and not required to do some form of service or make payments.

All this happened in a natural, spontaneous manner. It was as if the ashram had accepted me as a family member, and when we visit our home where do we stay - not in some rented room?. How fortunate I felt. It was all Bhagavan's grace.

Sanskrit

In my youth, when I was attending a Christian school, I began to study Sanskrit. However, the school decided to drop this subject from their curriculum soon after my studies began. Later in life, when I left the university and directed all my attention toward the spiritual ideal, I resumed studying Sanskrit on my own. But for some reason or other, these studies didn't proceed well either and I soon dropped them. Then, when I settled down at Aurobindo Ashram, I again thought I should take up the study of Sanskrit. The main focus in language at Aurobindo Ashram was to improve our proficiency in English, not Sanskrit; and although I did improve my English considerably at Pondicherry, Sanskrit studies remained an unfulfilled aspiration.

One evening, after I had settled in Bhagavan's ashram, I saw two large volumes and an oil lamp on the stool next to Bhagavan's couch. I asked Bhagavan what those books were. He told me that they were two volumes of Yoga Vashistam, a famous Sanskrit text, and then went on to extol the wisdom of the verses in the books. Regretting my inability to learn Sanskrit, I told Bhagavan that although I had attempted to learn the language three times, to that day I had learned very little. He kindly replied, "I don't know much either. I don't even know rama sabda - the first rule of Sanskrit grammar." This encouraged me to learn more Sanskrit in Bhagavan's presence, especially as I noticed how Bhagavan took great interest in Sanskrit compositions and was all praise for Ganapati Muni's mastery over the language.

One time a Sanskrit professor from Annamalai University was in the hall speaking to Bhagavan in Sanskrit. Bhagavan could understand spoken Sanskrit, but didn't speak it himself. He was closely following what the professor was saying and I, sitting nearby, was also able to grasp most of what was being said. When this had gone on for some time, all of a sudden, I lost the thread of the conversation. At that very moment Bhagavan turned to me and asked, "Did you follow that?" I was amazed how he caught me at the very moment I got lost.

Once Bhagavan mentioned about a Sanskrit biography of Saint Manikkavachakar. The particular book he was speaking about was a transliteration of the Sanskrit text into Telugu. Some of us devotees took it upon ourselves to locate this book and bring it to Bhagavan. We searched long and hard, as it was out of print for many years. Finally we were able to secure a copy from the estate of an influential zamindar (landholder). When we presented it to Bhagavan he seemed pleased and then asked me to begin reading aloud in the hall. I began and, as the time passed, Bhagavan's head leaned back on the pillow and his eyes shut. An old devotee of Bhagavan, one Subba Rao sitting by my side, signalled me to stop reading, as it looked obvious that Bhagavan had dozed off. I didn't stop immediately, but after his repeated silent requests, I stopped. The instant I stopped Bhagavan opened his eyes, looked at me and asked why I stopped. Usually we could not tell if Bhagavan was asleep or awake, though, in reality, he was always awake, awake to the Self.

Sometimes we would approach his couch, see him reclining with his eyes shut and softly say, "Bhagavan." I suppose we thought if we spoke softly and he didn't hear us, it meant that he was sleeping and, if he did hear us, he would respond without us disturbing him, as he was obviously awake and just resting his eyes. But however we reasoned, whenever we approached him in this manner, he would immediately open his eyes and say, "Yes, what is it?"

The Sanskrit recitation of the Vedas morning and evening in Bhagavan's presence was usually well attended. Initially, some priests from the main temple in town began coming and reciting before Bhagavan, thinking, perhaps, it was edifying for them to do this in the august presence of the Maharshi. Although everyone liked this, it was not performed with any consistency, depending mostly on the whims of the priests. The Sarvadhikari thought the ashram should have similar daily parayanas in a routine way. With this end in mind, a Veda Patasala, or Vedic school, was established in the ashram. The students, much like today, would come twice a day and recite before the Maharshi. Now the only difference is that they recite before Bhagavan's tomb. Bhagavan often commented on the value of listening to the Vedic chants. We would normally see him sitting fully alert and absorbed throughout the duration of these recitations.

In 1942, Bhagavan was near the back steps of the ashram when he abruptly placed his stick before the path of a dog that was in hot pursuit of a squirrel. In this successful attempt to save the squirrel, he lost his balance and fell, fracturing his right shoulder. Soon after this incident, when I was taking leave of Bhagavan to visit my village, I looked at the bandaged shoulder and wanted to ask him how he was feeling. But how could I? I knew perfectly well what his reaction would be to such a question regarding his physical well-being.

Reaching my village, I wrote a letter to Bhagavan in which I quoted the following verse:

'It is improper to make inquiries about the health and welfare of those whose sole delight is in the Self, since they are strangers to those mental states which distinguish between weal and woe.'

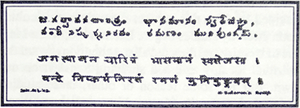

In addition to this, I also included a short Sanskrit verse that I composed.

When I returned to the ashram, one of Bhagavan's attendants told me that on the day my letter arrived, Bhagavan removed it from the other letters and put it by his side. He later returned all the letters except mine. Subsequently, he asked the attendant to bring him the big notebook in which all the verses composed on Bhagavan were recorded. Then, in his own hand, he copied the Sanskrit verse I composed into the notebook. He not only copied the Telugu script, which I had written it in, but also transliterated it into the Devanagari script. Then, with a red ink pen, he artistically framed the verses using two close parallel lines, one thicker than the other. The finished product looked like a piece of art. When I heard all this from the attendant and saw what Bhagavan had written in the book, I was very moved by the solicitude and attention he extended to me.

Many years later I asked President T.N.Venkataraman if I could cut out from that big book my verse written by Bhagavan. He gave me permission and I now keep it in my album containing photos of Bhagavan. Below is a copy of what Bhagavan wrote in the notebook, followed by my English translation.

'I salute Ramana, who shines by the effulgence of the Self, who delights in non-action, and whose life purifies the world.'

In January of 1946, Bhagavan came across a verse in the Srimad Bhagavatam that seemed to have appealed to him immensely. He first found it in the Tamiḷ Bhagavatam and then searched and found it in the original Sanskrit Srimad Bhagavatam. He then made his own Tamiḷ rendering of it and, at my request, translated it into Telugu, my mother tongue. Because Bhagavan was giving this verse so much time and attention I naturally thought it must convey a special meaning, especially in regard to his own spiritual experience. The literal translation in English is:

'The body is impermanent (not real). Whether it is at rest or moves about, and whether by reason of prarabdha it clings to him or falls off from him, the Self-realized siddha is not aware of it, even as the drunken man blinded by intoxication is unaware whether his cloth is on his body or not.'

Bhagavan showed me his Telugu translation and asked me to correct it. When I protested, saying, "How can I correct Bhagavan's writing?" he simply said that he must take advice from those who are proficient in whatever language he happens to use.

Dreams

'We are such stuff

As dreams are made of and our short life

Is rounded by a sleep.

Shakespeare really did know what he was talking about and it was not just poetic effervescence. Maharshi used to say exactly the same.

I suppose I questioned Bhagavan more often on this subject than any others, though some doubts always remained for me. He had always warned that as soon as one doubt is cleared another will spring up in its place, and there is no end to doubts.

"But Bhagavan," I would repeat, "dreams are disconnected, while the waking experience goes on from where it left off and is admitted by all to be more or less continuous."

"Do you say this in your dreams?" Bhagavan would ask. "They seemed perfectly consistent and real to you then. It is only now, in your waking state that you question the reality of the experience. This is not logical."

Bhagavan refused to see the least difference between the two states, and in this he agreed with all the great Advaitic Seers. Some have questioned if Sankara did not draw a line of difference between these two states, but Bhagavan has persistently denied it. "Sankara did it apparently only for the purpose of clearer exposition," the Maharshi would explain.

However I tried to twist my questions, the answer I received was always the same: "Put your doubts when in the dream state itself. You do not question the waking state when you are awake, you accept it. You accept it in the same way you accept your dreams. Go beyond both states and all three states including deep sleep. Study them from that point of view. You now study one limitation from the point of view of another limitation. Could anything be more absurd? Go beyond all limitation, then come here with your doubts."

But in spite of this, doubt still remained. I somehow felt at the time of dreaming there was something unreal in it, not always of course, but just glimpses now and then.

"Doesn't that ever happen to you in your waking state too?" Bhagavan queried. "Don't you sometimes feel that the world you live in and the thing that is happening is unreal?"

Still, in spite of all this, doubt persisted.

But one morning I went to Bhagavan and, much to his amusement, handed him a paper on which the following was written:

'Bhagavan remembers that I expressed some doubts about the resemblance between dreams and waking experience. Early in the morning most of these doubts were cleared by the following dream, which seemed particularly objective and real:

'I was arguing philosophy with someone and pointed out that all experience was only subjective, that there was nothing outside the mind. The other person demurred, pointing out how solid everything was and how real experience seemed, and it could not be just personal imagination.

'I replied, "No, it is nothing but a dream. Dream and waking experience are exactly the same."

''You say that now," he replied, "but you would never say a thing like that in your dream."

'And then I woke up.'

The Four Paths

Maharshi: An examination of the ephemeral nature of external phenomena leads to vairagya. Hence enquiry (vichara) is the first and foremost step to be taken. When vichara continues automatically, it results in a contempt for wealth, fame, ease, pleasure, etc. The 'I' thought becomes clearer for inspection. The source of 'I' is the Heart - the final goal. If, however, the aspirant is not temperamentally suited to Vichara Marga (to the introspective analytical method), he must develop bhakti (devotion) to an ideal - may be God, Guru, humanity in general, ethical laws, or even the idea of beauty. When one of these takes possession of the individual, other attachments grow weaker, i.e., dispassion (vairagya) develops. Attachment for the ideal simultaneously grows and finally holds the field. Thus ekagrata (concentration) grows simultaneously and imperceptibly - with or without visions and direct aids.

In the absence of enquiry and devotion, the natural sedative pranayama (breath regulation) may be tried. This is known as Yoga Marga. If life is imperilled the whole interest centers round the one point - the saving of life. If the breath is held the mind cannot afford to (and does not) jump at its pets (external objects). Thus there is rest for the mind so long as the breath is held. All attention being turned on breath or its regulation, other interests are lost. Again, passions are attended with irregular breathing, whereas calm and happiness are attended with slow and regular breathing. A paroxysm of joy is in fact as painful as one of pain, and both are accompanied by ruffled breaths. Real peace is happiness. Pleasures do not form happiness. The mind improves by practice and becomes finer just as the razor's edge is sharpened by stropping. The mind is then better able to tackle internal or external problems.

If an aspirant be unsuited temperamentally for the first two methods and circumstantially (on account of age) for the third method, he must try the Karma Marga (doing good deeds, for example, social service). His nobler instincts become more evident and he derives impersonal pleasure. His smaller self is less assertive and has a chance of expanding its good side.

The man becomes duly equipped for one of the three aforesaid paths. His intuition may also develop directly by this single method.

Celebration of Sri Ramana Maharshi's

Advent at Arunachala

In honour of the 99th Anniversary of Sri Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi's arrival at Sri Arunachala, devotees gathered at Sri Arunachala Ashrama at 72-63 Yellowstone Boulevard, Queens, New York City on Sunday, September 3rd.

Having learned of the celebration via the World-Wide Web computer network, a good number of new friends joined us, travelling from Massachusetts.

The program began with the devotees singing Sri Ramana Maharshi's composition 'Sri Arunachala Akshara Mana Malai' (The Marital Garland of Letters). Sri Arunachala Bhakta Bhagawata then gave a moving message, inciting us to deepen and stabilize our practice of Self-Enquiry and Self-Surrender.

Bhajans were offered by several ladies, initiated and inspired by the transparent sweetness of devotional songs from our youngest devotee, Radha Ramaswami Devi - just seven years of age!

Puja was offered to Sri Bhagavan with flowers, led by Professor Chhaya Tiwari. All present chanted the 108 Names of Bhagavan. Professor Chhaya, a dedicated Sanskrit scholar and devotee, also caused our humble sanctuary to resonate with her inspired chanting of Chapter eighteen of Ganapathi Muni's Sri Ramana Gita. The mood of the celebration was one of gratitude and rejoicing.

After the lights of ārti were offered, and after most of the devotees had left, following a sumptuous feast, Mrs. Kanthimathi Venkatraman arrived and poured out her heart in a Tamiḷ song which she had especially composed for the occasion.

Its English translation follows:

As Azagu and Sundaram you came to this world like a 'wonder', O Ramana!

You stood as the pillar of light which has no beginning or ending, O Ramana!

I am being pulled on both sides by the forces of pleasure and pain, O Ramana!

Come and be present in my heart, O Ramana!

In spite of all the six senses that I have, I am feeling like a fool, O Ramana!

Comfort me and bestow knowledge of Atma, O Ramana!

In this tiny boat of worldly life I am being tossed, O Ramana!

Come to my rescue before I sink to the bottom, O Ramana!

Save me from the thieves' snarls, namely desire and anger, O Ramana!

Be known that I have no other savior but you, O Ramana!

Having lost my direction and no one to guide me I am roaming hereand there,

O Ramana!

Come and ward off all the evil and save me, O Ramana!

Like a crop for want of water, I am dying. Give me life, O Ramana!

Come and appear before my searching eyes, O Ramana!

As camphor lighted, you merge into the jyothi of Arunachala, O Ramana!

You seat yourself firmly in the hearts of those suffering devotees who pray to you, O Ramana!

Mrs.Kanthimathi Venkatraman is 73-years-old and is the Mother of Girija Arakoni, who brought her to the Ashrama on that day.

In the Nova Scotia Arunachala Ashrama one hundred and fifty guests attended the day's celebration in Sri Arunachala Ramana Mandiram, traveling long distances from different Maritime Provinces and Northeastern U.S.A.

Mr.Yashwant Rai conducted the program, beginning it with Ganesha Puja. Raju Parekh recited Shanti Mantrams and Dennis Hartel gave a short welcoming talk in which he explained how Venkataramam, an apparently normal school boy, was transformed in a few moments of Self-Inquiry to a Sage, and how he travelled from Madurai and arrived at the Holy Arunachala Mountain on September 1, 1896.

Then many bhajans and stotrams were offered, as one after another came forward and sang. Dr. Subbarao Durvasula gave a short talk on the historical significance of Sri Ramana Maharshi's incarnation. He quoted Ganapathi Muni's prophetic Sanskrit verse:

dakṣināmūrti sārambhām

śaṁkarācarya madhyamām।

ramaṇācarya paryantām

vande-guru paramparām॥

'Obeisance to the line of preceptors

with

Dakshinamurti in the beginning,

Sankara in the middle and

Ramana in the end!'

The devotees then recited Sri Ramana Maharshi's composition, 'Upadesa Saram,' followed by the chanting of 'Arunachala Siva.'

Aarti was performed, and outside on the spacious lawns surrounding the temple, meals were served to all the devotees.