Ramana Yoga Sutras

Part 5

Sri Ramana Maharshi wrote these Sutras at the request of some devotees to benefit their sadhana. Sri Krishna Bhikshu (Voruganti Venkata Krishnaiah) was one of the early and ardent devotees of Bhagavan. He lived in the Ashram with Bhagavan for many years and wrote Ramana Leela, the life of Bhagavan in Telugu.

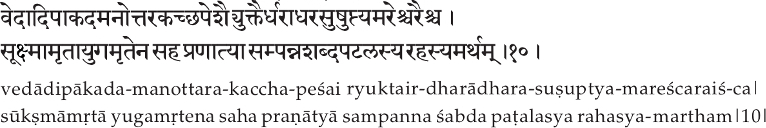

After talks on “Ramana Yoga Sutras” were given by Sri Krishna Bhikshu at the Ramana Satsang, Hyderabad, these Sutras were published in Telugu in 1973 and then in English in 1980. We conclude in this issue, with sutras eight to ten along with their commentaries.

VIII

“aham aham iti”

As ‘I-I’

1. The direct experience that comes to a sadhaka as a fruition of his endeavors is the experience of the Ultimate as ‘I-I’. In the negative way, various descriptions have been given of this experience, e. g., “It is neither light nor darkness; it gives light so it is called The Light. It is neither knowledge nor ignorance; it gives knowledge, so it is Knowledge (chit).” In modern language too: “It is not being nor becoming, but it exists; therefore it is called Sat, in contrast to all other things that disappear.” Bhagavan calls this experience the ‘I-experience’. In that state one must have been there to experience it; it must be devoid of any other experience, then only can it be said to be the Self and nothing else.

2. Some have questioned: ‘There being only one experience, why should Bhagavan have used two I’s (‘I- I’) to describe it?’ One explanation is, the second ‘I’ does not indicate a subsequent experience, but is used to ‘confirm’ the experience. Others say, “In nirvikalpa samadhi, you get a similar experience, but it is not continuous — like the flash of lightning, it appears and disappears — so two I’s are used. Finally, the experience becomes a continuous one.

3. We may add that in this experience of yoga there is a slight tinge of individuality and the mind can be said to exist in a very, very rarified state called ‘visuddha sattva’. But in actual experience it makes no difference. The experience is something like a throb. That is why it may be called ‘jnana spanda’ (a throb of knowledge).

IX

‘brahma matram’

Only Brahman

People knowledgeable of Sastras will question whether the Atman experienced can be real because the experience may be of only a short duration. They also say that in the texts the Atman is said to be infinitesimally thin (thanvi), but Bhagavan says It is big, too. How is this to be reconciled? The texts themselves give the answer, which Bhagavan has also repeated: “Smaller than the smallest and bigger than the biggest...” says the Upanishad.

The Sruti says, “ Verily all this is Brahman”. Then can there be no difference between the Atman and the Brahman? In the Atman there is the superimposition of the manifested cosmos which alone is apparent to you and which prevents your experiencing the Atman as Brahman. In the state of knowledge, the superimposed mental knowledge disappears, and, call It whatever you will, Atman or Brahman, It alone remains, without a second. As the Sruti says: ‘Ekameva’ (only one), ‘Adviteedyam’ (no second).

X

‘kevalam’

Only

Philosophy expounds three types of differences: ‘sajateeya’, the difference between a horse and another horse;‘Vijateeya’, the difference between a horse and a cow; ‘Svagata’, the difference between the hand and the foot in one’s person. Bhagavan says that none of these types of differences exist in Brahman. It is like an ocean — all salt water, though not totally like an ocean because salt exists there in a state of dissolution. There is nothing dissolved in the Atman. It is pure.

This aphorism is necessary to controvert the position that Brahman is saguna (with form). Otherwise, how could a cosmos with various attributes come out of It? Bhagavan says, “No, It has no attributes; It is purna, undefiled by any admixture.” It is, in Sanskrit, ‘ghana’, not giving scope to any other thing. The Ultimate is anandaghana, not anandamaya.

Epilogue

These aphorisms are the very words of Sri Bhagavan. All but one of them have been taken from the first Sanskrit verse he wrote in about the year 1913, the famous “Hrdaya Kuhara” sloka found in Chapter II of Sri Ramana Gita. Aphorism number four has been taken from Ramana Gita itself (Chapter VI, v. 5). Bhagavan himself gave several of the explanations. The rest has been culled from other philosophical texts, so that the author of this brochure makes no claim for originality. Nor does he claim that Bhagavan’s teaching, except in one point, is original. So far as he is aware, Bhagavan’s teaching and explanations are in tune with the best traditional Advaitic thought and texts.

Initiation by Look

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

I stop in the Gratitude Hut during my walking meditation. Upon entering, my eyes immediately become fixed on a large photo of Ramana Maharshi which hangs on the wall. I cannot take my eyes off of him. I am magnetized. It seems he, too, is looking directly at me.

As I gaze into his eyes, his image takes on a form that seems lifelike, multidimensional; it’s as if he is right here, now. His face becomes luminous and his expression softens, as if to say, “Yes, I am looking at you.” A couple of more crow’s feet appear at the outer edges of his twinkling eyes and his lips turn up ever so gently

as he smiles warmly at me. His kind look is penetrating; truly, it’s as if he is looking into me and through me. I feel a profound sense of intimacy, into-me-see, of being seen so completely and fully in this moment.

Something shifts ever so slightly, and his eyes take the form of luminous white fire. I feel a burning sensation. No longer am I the object of his gaze; I experience myself gazing into myself — subject and object at once. I am seeing myself through his eyes. He is showing me my own True Nature! It is as if Sri Ramana is lending me his eyes so that I can see what he sees — the Self that I Am.

Tears stream down my face and I am filled with a profound sense of wonder, and awe, and connection. I sense that I am not separate, or alone; in this moment all are one — the wooden hut and the photo and Sri Bhagavan and I, and the trees and the sunlight, and then, in this new moment, I am Formlessness, Timelessness, Consciousness.

If Only It Were Chadwick

title="listen to this article, 15m49s, 11.7 MB mp3 naration">Louis Buss lives in London. He is presently engaged, both in England and India, in extensive research into the life of Major A. W. Chadwick (Sadhu Arunachala). (continued from the Sep-Oct issue)

Part III

I Sit With Him Here

AS I leafed onwards, I found that almost every photograph had an inscription of some kind. Some of these seemed quite superfluous. Above one picture, he had written A disciple; above a picture of Bhagavan as a young man, he had taken the trouble to write The Maharishee as a young man. Anyone who read the book would have had no need of these little explanations, so he again seemed to be working on the assumption that his parents wouldn’t bother.

But other inscriptions were more revealing. Above a picture of Bhagavan and Lakshmi, he had helpfully written The sacred cow of the Ashram — and it was impossible not to wonder how talk of sacred cows would have gone down in 30s England. Below this is a picture of the Old Hall. The inscription is smudged, as if someone had nodded off while reading the book in the bath, but it is just about possible to make out:

This is the room where the Maharishee sits for meditation. I sit with him here too with the other disciples.

How strange that his readers might not have instantly recognised the famous Old Hall, and that they might have imagined their son went there for private meditation sessions with this strange Maharishee!

Above a picture of the Arunachaleswara Temple, he had written:

The Eastern Gate of the marvellously beautiful temple to which I go each evening for meditation at the shrine of Krishna.

So presumably his routine had been to visit the temple early in the evening, then return to the Ashram later and end the day in the ‘vital presence of the Maharishee.’ This seems to be confirmed by the very last inscription. The picture shows the entrance of the Ashram, which, if it weren’t for the familiar archway, would be quite unrecognisable to visitors of today. No cars or lorries are visible, no auto-rickshaws or motorcyclists swerving by with mobile phones crooked to their ears, no backpackers or ignorant Westerners like myself, wandering round with a slightly bemused air as they wonder at exactly which point they are supposed to remove their shoes. There are only two white-clad figures in the foreground, whose stance somehow conveys the entrancing peace of the place. One stares away to the left as if he has been distracted by the distant creaking of a bullock-cart, whilst the other looks towards us — no doubt it was still a rare thing to see anyone actually taking a photograph. The archway itself seems to have appeared by a forest path in the middle of nowhere. There isn’t even a wall on either side, so that it looks slightly surreal, like a checkpoint marking a non-existent border. Why bother having an archway at all when anyone can just walk round it, and there is no apparent difference between this side of it and that? But, of course, this is no ordinary threshold. It is a magic portal, like the door of an enchanter’s castle or the shore of Prospero’s isle. If it seems to serve no apparent purpose, that is because this is a dream archway and the domain it protects is not visible to the waking eye. Things may look and feel exactly the same after you have stepped underneath, but in fact you will have passed through the looking-glass. From then on you may at any moment suffer a sea-change, into something rich and strange.

The mystery devotee had drawn an arrow through the arch, next to which he had simply written:

I walk along here each evening. I was left feeling that the whole thing was just a sort of glorified postcard. Even if his family could never understand Bhagavan or His philosophy, this Englishman abroad wanted to make sure that they formed at least some idea of the exotic place in which he was living. He wanted them to know what it was like to meditate in the temple each evening, then to walk back through the magic arch and settle down with the other victims of the enchantment at the feet of that strange Indian Prospero. But he could surely have had no conception of how much he would be revealing to another English reader, far away in some fantasy future of space-stations and microchips. All unknowingly, he had told me much about his relations with his family, his life in India and his devotion to Bhagavan. I felt I knew him now and, even though he would never understand it himself, that we were friends. I also had the strange sense that I was the intended recipient of this book. It might have passed through many hands, but the fact that it had ultimately washed up in the great jumble sale of Ebay, and in such woeful condition, proved that it had never been treasured at its true worth. It had been smudged with dirty fingers, exposed to rain or bathwater, and unceremoniously used as a coffee-mat. Only now, after who knew what other trials and indignities, had it finally arrived in the hands and the home of someone who could understand its true value. It was impossible not to feel that, some seventy-five years after it had been posted from Tiruvannamalai, the book had finally reached its destination.

All of which gave me the absurd but inescapable feeling that my destiny was somehow linked with that of the Mystery Devotee. This in turn made me more eager than ever to find out exactly who he had been — because, if fate had really chosen to connect us, the revelation of his identity would also reveal something about my own.

As soon as I had finished leafing through the book, I drove up to show it to my sister, a fellow devotee who lives nearby. We did our best to take some professional-looking photographs of it to put up on the Internet. I then came home, uploaded the pictures, and sent the link to a few people I knew would be interested. Soon enough, the emails were flying back and forth between England, America and India as we tried to work out who the Mystery Devotee might have been. And the first name on everyone’s lips was Chadwick’s.

Now, I don’t mind admitting that I had hoped it would be he. If my destiny was to be linked with anyone’s, I could think of nobody I’d rather it be than Chadwick. From the moment I’d seen the date the book had been sent back from India, I’d secretly longed for it to be his, and I am sure that most devotees in my position would have felt the same. All of us have a soft-spot for Chadwick. Of all the impressive, extraordinary and inspiring figures who were drawn to Bhagavan, I can think of no other who so cries out to have the words ‘good old’ placed before his name. ‘Good old Osborne’ somehow doesn’t come so naturally. As for people like Ganapati Muni and Muruganar, the very idea of putting those words before their names is somehow so incongruous and disrespectful that I don’t think I could ever do it, even as a joke. ‘Good old Chadwick’, on the other hand, seems not only natural, but somehow inevitable. If I try to think what might have happened if I had met Arthur Osborne, I can imagine us hitting it off in a way, perhaps with me struggling to keep up my end of a highbrow discussion of theology or comparative religion. In the case of Ganapati Muni, I would have been too awestruck to have opened my mouth, and in the case of Muruganar I think I would have been too overwhelmed by admiration and love. But I can easily imagine myself pumping Chadwick’s hand, giving him a hearty slap on the back and saying something like, ‘Good old Chadwick! I’ve heard so much about you, my dear chap! What a great pleasure to shake your hand at last!’ Then, possibly over tea and crumpets, we would settle down to a long discussion of the paths that had brought us both to Bhagavan, and how wonderful He was, and what miraculous changes He had wrought in us both. We would part as the best of friends, with me feeling I’d known the dear fellow for years.

On the Glory of the Sidhhas

Chapter 18 of Sri Ramana Gita

7. Pitiless to his body, strict in the observance of discipline, wholly averse to the delights of the senses, he is a Sage without anger or desire, beside himself with the joy of pure awareness.

8. Free from infatuation, greed, distracting thought and envy, he is ever blissful. He is ever active in helping others to cross the sea of relative existence, regardless of reward.

9. When Ganapati, saying “Mother is mine” sat on the lap of Parvati, Kumara retorted “Never mind, Father is mine” and got on to Siva’s lap and was kissed by him on the head. Of this Kumara, who pierced with his lance the Krauncha Hill, Ramana is a glorious manifestation.

10. He is the mystic import of the mantra “Om vachadbhuve namah (Salutation to the fire of Brahman whence emerges the Word).”

11. He is an ascetic without danda (a staff carried by ascetics), yet he is Dandapani (Kumara). He is Taraka (the ferryman for crossing the sea of suffering), yet he is the constant foe of Taraka (the asura). He has renounced bhava (relative existence) yet is a constant worshipper of Bhava (Siva). He is hamsa (Lit. a swan, a paramahamsa), yet without attachment to manasa (A lake in the Himalayas, a favorite home of swans. Alternatively, he has no attachment to mind).

V.Ganapati Sthapati (1927—2011)

Part 1

Born in 1927, V. Ganapati was the son of Sri Vaidyanatha Sthapati and Smt. Velammal. His father was the builder of the Mathrubhuteswar Temple at Sri Ramanasramam. In the following article the late V. Ganapati Sthapati writes about the two Maharshis to whom he attributes his enormous success in restoring and elevating the status of traditional Hindu architecture in modern Indian society and throughout the world.

DURING my formative period as a student and during my professional career as a Sthapati I had the good fortune of coming under the influence of two Maharishis of world-wide renown.

During my boyhood, from 1939 to 1949, my father Sri Vaidyanatha Sthapati, was working as the architect and builder of the Sri Mathrubhuteswara Temple at Sri Ramanasramam in Thiruvannamalai. This was the temple built over the samadhi of the holy mother who gave birth to Bhagavan Ramana. I was around 13 when my father started building the temple and also sculpting the holy image of Bhagavan Ramana in stone.

The Maharishi appears to have scarcely spoken to devotees, however devoted they were. But fortunately he used to talk to my father whenever he approached him for advice on any issue. I used to stand by his side on such occasions. In the meantime, for the sake of my education, my father had to shift to Salem for the construction of a temple there. I did my SSLC and intermediate in the local college. Still my father and I used to visit the Maharishi on work. During such visits I closely watched the face of the Maharishi which was always lustrous whenever the talk turned to our family affairs and on me. He never enquired about my studies, but he used to look at me with a kind smile which I interpreted as a flow of grace.

On one fine morning the results of the Intermediate Examination appeared in the newspapers. To our surprise, there was a call from the Maharishi to which my father and I responded at once. All the time there was a large gathering of devotees in what is called Bhagavan’s Hall. There was a newspaper in the hands of the Maharishi. Both of us standing near his Yogasana, he spoke to the devotees with inestimable joy, saying, “Sthapati’s son has passed the examination with distinction. His future is going to be very bright.” We were dumbfounded. Not even a word of thanks could we utter — so much were we choked by joy. In response, we could do nothing but to prostrate before him and silently take His blessings.

The next thing for my father to do was to send me to the Engineering College, Guindy, Madras. It was in 1947 that I applied and without any difficulty I got a seat, thanks to my high marks. But my father’s dream did not come true. Though my father was then a leading Sthapati in the field, he had no financial resources. The fee that I had to pay at the time of admission was only Rs.480. But for hostel and other expenses one had to pay around Rs.300 per semester. This was our problem. It was too much for him, as his monthly remuneration was only Rs.100. Because of this he was unable to make any decision for or against the Engineering College. Though he was poor he never during his life approached anybody for financial help. His idea was to send me to the Engineering College and utilize the knowledge of modern science and technology for the better understanding of the Vastu tradition and that I should work to promote and revive it.

Before he could take a decision, the date of admission expired and the whole family was upset. With stoic endurance my father kept silent for months. He never went even to the Maharishi for advice or help. A few months later the Maharishi called my father to his side and said “In your own native place a new college has now been established and it will start functioning from 15th August, 1947. I feel that it is only for him (meaning me) that this college has been started late in the year.” Taking the Maharishi’s words as divine direction, my father lost no time to admit me there. Unfortunately, it was not an Engineering College in the B.A. class, teaching Pure Mathematics as expected. The curriculum was different. But it was no other than the famous Dr. Alagappa Chettiar College, which was opened in Karaikudi on the first India Independence Day. I was too young to understand that this turn of events would be for the better and highly conducive for my career as a Sthapati later in life. We had full faith in the words of Maharishi and took the journey along the path he indicated. Only after I took up sthapatiship did I realise the value of the Maharishi’s direction. I am happy to say that it is because of his blessings that I am what I am today. The world around me knows today to what extent I have fulfilled my father’s dream. I am proud to say that I have gone up several steps ahead of my father’s expectation. This is because of another Maharishi’s intervention and direction that I was blessed with a career as a Sthapati.

The other Maharishi under whose influence I came next was His Holiness Paramacharyal of Kanchi. I had to leave the position of a Sthapati that I was enjoying under the Palaniandavar Devasthanam, Palani in 1961 to assume the principalship of the School of Sculpture and Architecture, a position my father had held from 1957 to 1960. My father had to retire as he fell seriously ill. He had a severe stroke, followed by a paralytic attack and was unable to speak. Even expert medical treatment was of no use. Finally, on the advice of Sri S. Ganesan “Kamban Adippodi”, I took him to Pillaiyarpatti (near Karaikudi) for Ayurvedic treatment. Sri S. Ganesan was my godfather since my early days. Even this Ayurvedic treatment produced no results.

It was around this time in 1963 that I met Paramacharyal when he was camping at Ilayattankudi, a village about 10 miles from Pillaiyarpatti where I was born. I had never met him before, though my father had known him intimately for many years. The intimacy between Paramacharyal and my father was at its all-time high when he was commissioned to build a stone mandapam in the premises of the Kanchi Mutt. This is the mandapam where pujas are performed today.