Whatever Became of Frank H.Humphreys

The First Westerner to Visit the Maharshi

The following paragraph, quoted from Arthur Osborne, is found in the “Prefatory Note” of the small book Glimpses of the Life and Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi, which is a compilation of articles written by Frank H. Humphreys:

“Police service did not prove congenial to Humphreys. Sri Bhagavan advised him to attend to his service and meditation at the same time. For some years he did so and then he retired. Being already a Catholic and having understood the essential unanimity of all religions, he saw no need to change, but returned to England, where he entered a monastery.”

Frank Humphreys was the first Westerner known to sit in the Maharshi’s presence and the brevity of this somewhat flawed epilogue leaves out a life of many adventurous undertakings that took place both before and after Humphreys was baptised a Catholic (brought up an Anglican) and took his first vows of a Dominican religious at the age of 37 (14 years after leaving India). Subsequently, he worked tirelessly for 45 years serving the needy in South Africa.

These facts of Humphreys’ life would have remained unknown if not for the effort of John Imes of Mississippi. Whatever scant evidence relating to Frank Humphreys’ life John uncovered over the course of one year, he kept on digging and persisting until he obtained, through the kindness of a Dominican archivist a copy of a short biography, Not So Trivial a Tale, compiled by his colleagues in 1975, after his passing. John also offered valuable suggestions for this article.

Frank Humphreys’ pre-religious life was a whirlwind of endeavors: First as a child misfit, then a gifted student who trained for diplomatic service, an Indian police officer, a student of Vedanta, an airman, an intelligence officer, a journalist, farmer, store manager, a postal employee, a teacher, a secretary, carpenter, and public speaker. All of these endeavors preceded his final profession as a Catholic priest.

Prologue

Beginning in 1911, a 21-year-old British police officer named Frank Humphreys had at least three face-to-face visits with the young Sri Ramana who was at the time living in the Virupaksa Cave. Fortunately, Humphreys recorded some of his experiences. He died in 1975 in South Africa, as a Catholic religious, a Dominican friar. To attempt to summarize his life between these two events, and to offer some conjecture as to the influence of Bhagavan and Vedanta on his life, is a daunting task for three reasons. First, sources are few for an informal, unscholarly article such as this. We have his own sparse notes of the visits in the form of letters to the editor of The International Psychic Gazette, published as Glimpses of the Life and Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi as Described by Frank H. Humphreys. We have excerpts taken by Dominican compilers from Humphreys’ unpublished autobiography in later life as a friar. The compilation is entitled Not So Trivial a Tale.[1] Second, Humphreys’ life from birth to death is an incredibly complex and unusual story, with many twists and turns. In many ways he is an enigma. Third, often his own words leave doubt as to what he really meant, so one can, of course, discern only clues to the influence that Vedanta may have had on him in later life.

No pun intended on vichara, but who am I to be attempting this? Frank Humphreys encountered Bhagavan early in life, became a Catholic in the middle, and ended up as a vowed Dominican friar. I write as one who encountered Catholicism early in life (16), became a vowed Dominican Sister in the middle (54), and now (75), am still firmly Dominican, but only a fringe Catholic and a devout Advaitin and devotee of Bhagavan. I find that Dominican life, based as it is on the four pillars of prayer, ministry, community life and assiduous study, has no conflict with Vedanta. In fact Vedanta fits well with Dominican life. I do find some disparity between the Roman Church’s doctrines and the essential teachings of Jesus.

The following is only my own observations and conjectures on the life of this unique seeker who was the first Westerner to experience the Divinity of the Maharshi and who ultimately dedicated his life to the service of God in all people.

Childhood and Youth, 1890 – 1910

Francis Henry Humphreys was born in 1890 in London, of High Anglican parents. His father was a struggling physician; his mother was interested in the occult and practiced fortune-telling, table-turning, second sight and later, Spiritualism. He recounts a visit he and his sister made to their mother’s latest fortune teller and tells how some “second sight” opened in him. In spite of his later disparagement of the influences of the occult – “I blame (my incompetence) on the kind of negative attitude of mind that the ‘occult’ sciences had on me”– he loved his mother and wrote later in life, “I am thankful to have had such a Mother, and her mistakes count for nothing beside her goodness.”

The almost unbelievable number of serious illnesses and surgeries Francis underwent in his lifetime began early, with blood poisoning and diphtheria at age 8. In spite of these, he appeared to be something of a child prodigy, with a propensity for languages enhanced by sojourns in France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. At Kings College London, at age 15, his plan to enter the Diplomatic Corps as a Student Interpreter in China did not materialize, and his mentors advised him to apply for the Indian Police (India was then part of the British Empire).

Indian Police; Flying; Intelligence

1910-1919

By this time Francis had also had two broken legs, eight months of illness and two operations. He passed the police examination low on the list due to ill health before and after. After nearly dying, he sailed for India in December, 1910. On arrival in India, he went into the Bombay Hospital with pleurisy and malaria and nearly died again. These numerous health misfortunes plagued him throughout his life: he had more than twenty-five serious operations and spent over seven years in hospitals at different times. His list of illnesses and broken bones takes up an entire paragraph in Not So Trivial a Tale.

He learned Telugu, one of the local languages, from S. Narasimhayya in Vellore. Narasimhayya was a disciple of Sri Kavyakanta Ganapati Muni and a devotee of Sri Bhagavan; it was they who brought Francis to Sri Bhagavan.

Narasimhayya records in the Introduction to Glimpses that Francis first asked him for an English book on astrology, then asked if he knew any Mahatmas, which he denied. The next morning Francis said, “I saw your Guru this morning in my sleep!” and picked out Ganapati Śāstṛi’s photo from several that Narasimhayya showed him.

Francis again became ill and had to go to a hill-station for recovery. His first letter to Narasimhayya described his “meeting” with a strange man, poorly clad, well built, with bright eyes, matted hair and a long beard. Narasimhayya believed it must have been a siddha. His second letter was a request to teach him breath-control. His third brought questions about eating meat, and fourth letter asked if he could join a “mystic society”. He was then almost 21. Narasimhayya answered as best he could but avoided his questions about unusual practices.

One day, after Francis returned from the hill-station in 1911 to resume his police work in Vellore, he “drew a picture of a mountain cave with some sage standing at its entrance and a stream gently flowing down the hill in front of the cave. He said he saw this in his sleep, and asked what it could be.” Was this Bhagavan’s call to Francis from the Virupaksha Cave? What good deed had Francis done in a previous life to merit the blessing of face-to-face visits with Him? Narasimhayya and Ganapati Śāstṛiar subsequently took Francis to meet the young Swami at Virupaksa. The Not So Trivial a Tale compilers mention only his meeting with Narasimhayya and Ganapati Śāstṛiar in one short paragraph – no mention at all of meeting Sri Ramana. Had Francis himself noted anything more, years later, in his unpublished autobiography?[2]

After the visits, Francis sent letters to The International Psychic Gazette describing his experiences in Bhagavan’s presence. Only a few short quotations from Glimpses are given here to show the impact these experiences obviously had.

“When we reached the cave we sat before Him at His feet and said nothing. We sat thus for a long time, and I felt lifted out of myself.”

“I could only feel His body was not the man, it was the instrument of God, merely a sitting motionless corpse from which God was radiating terrifically. My own sensations were indescribable.”

“He conveyed worlds of meaning and taught me direct...”

“You can imagine nothing more beautiful than His smile.”

“I sat for three hours listening to His teaching.”

“It is strange what a change it makes in one...”

The teachings according to Francis’ notes:

“...try to keep the mind unshakenly fixed on That Which Sees. It is inside yourself.”

“That one point where all religions meet is the realization...the fact that GOD IS EVERYTHING, AND EVERYTHING IS GOD.”

“These bodies and minds are only the tools of the ‘I’, the Illimitable Spirit.”

“How can you best worship God? Why, by not trying to worship Him but by giving up your whole self to Him, and showing that every thought, every action, is only a working of that One Life (GOD).

These are Francis’ own words, recorded shortly after being in Bhagavan’s presence.

But – back to his biography:

Francis found police work in the Raj difficult: “Frustration, boredom, overwork, blistering heat, malaria...and a good deal of (crime) was a matter of a goat stolen by someone who was starving...” In another district: “...he had nine murders, a threat of riot and the discovery of a large gang of bandits, in one week.” After two-and-a-half years Francis returned to England.

Then followed another illness, a two-year liaison with a much older woman, writing, and flying lessons in 1916. In 1917, he was sent to France with the Royal Flying Corps, later the R.A.F. Airplane fumes soon gave him bronchitis and he was sent back to England. After War Office work, teaching aircraft gunnery training, and being a Flight Instructor, a crash in 1918 caused by a student landed him in a hospital for ten months with fractured facial bones. He studied with a theologian, Mr.Bowhay, and asked, “‘What is the difference between Vedanta and Christianity?’ Mr. Bowhay replied, ‘...Vedanta claims that everything is from yourself, Christianity teaches that everything is from outside you.’ ‘This reply’, Francis remarks, ‘worked a revolution in me. I became a Christian again.’”[1] Quotations in this article are from this compilation, by Br. Oswin Magrath and Br. Finbar Synnott.

[2] When he was almost 70 years old, Br. Humphreys’ superior asked him to write an autobiography. The only known copy of this work, entitled Not So Trivial a Tale, exists in the Dominican archives in Springs, S.A. The archivist says there are about five pages that deal with this period, mostly recounting conversations. Unfortunately, the typescript was too faint to duplicate.

Ella Maillart of Switzerland

Part III (conclusion)

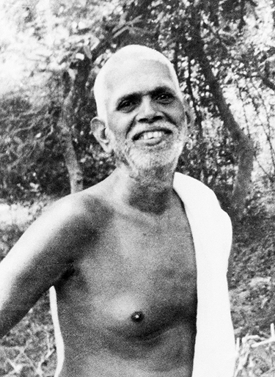

With this final installment we conclude our short description of the life, aspirations and realizations of a woman who in the early 20th Century gained world-wide fame from her fearless adventures in the remotest parts of the globe. Ella Maillart’s incessant desire to discover uncharted territory ultimately landed her at the feet of the Maharshi where she realized that the true journey and destination is the discovery of the ever-present Self within.

After Maillart’s return to Switzerland she was requested to send an article for Bhagavan’s 1946 Golden Jubilee Souvenir, [1] which she titled, “The Sage’s Activity in Inactivity”.

In the article she advances many insights about Bhagavan’s exalted state and his ultimate beneficence to the whole creation, which can so easily be misunderstood by the Western savants. She begins her contribution with the following remarks:

“According to my actual understanding it would be foolishly daring of me to write something about Sri Ramana himself, the mode of life of a sage being an abysmal mystery but for those who enjoy a similar state of consciousness.

How and to whom can be described what is experienced within by one who is desireless, whose sorrow is destroyed, and who is contented with repose in the Self?

“Neither can I be so bold as to add my gloss to the commentaries that have already been made on the Maharshi’s “Forty Verses”. Who am I to do it? Would it be of any help to anyone, and is it not much better to let Sri Ramana, the Teacher, comment on them himself, if and when he thinks it could be of any use?

“As for descriptions of the life at the Ashram in Tiruvannamalai, I don’t think it is within my power to depict the subtle atmosphere which renders the place unique in its setting of dry and hard beauty.

“Nevertheless, I would like a small token of homage to reach the feet of Sri Ramana from me as a pledge of my gratefulness.And he will perhaps be indulgent enough to accept the following lines about a thought that occurred to me.”

After her return to Switzerland she added an additional last chapter to her French edition of Cruises and Caravans. In it she openly reveals her lifelong spiritual aspirations and how the few years she spent in India resolved all her doubts and led her to the path of Self-Enquiry of “Who Am I?” Excerpts from this chapter follow.

Chapter XIV

South India

[3]

“Since book learning never really suited me, my idea was to take some time living with a sage whose behavior would oblige me to grasp what eluded me intellectually. I learned about two seemingly genuine spiritual masters from two French friends who were familiar with India.

“The world attracts us by its marvels and by its adorable beauty even before we start to feel that, indeed, it has a hidden meaning. We start to study it; we go off to conquer it, looking for whatever satisfaction it could bring to our deepest desires.

“But none of the multiple aspects of the world can give us the fundamental answer. That can only come from God, and where else is God other than within us. Everyone has to discover this (fundamental) truth on his own. The spiritual being, hidden within us, is the living source of our deepest aspirations, and those aspirations will never be fulfilled unless (the deeper being) is liberated. In many of us, it is impotent, paralyzed because it has been neglected, and the power to bring it back to life lies within the heart and not in the brain. I am not saying all this because someone taught it to me, but because I have experienced the truth. In my view, it is the most important truth that has emerged from everything that I have seen or understood; it is the sum of all my discoveries. Today I feel fulfilled, and even though I live alone, never again will I suffer from loneliness.

“India for me was the beginning of a completely new voyage that would lead me to the full and harmonious life that I was instinctively looking for. To undertake this journey, first I had to understand the “unknown lands” of my own spirit.

“I was lucky enough to make a few hundred rupees from the screening of my film on Afghanistan in Bombay. I had taken leave for 18 months so I could try to live like a Hindu in the south of this great country. That would give me enough time to decide whether Hindu wisdom (actually) suited me.

“I made several brief trips to Pondicherry where I went to visit Sri Aurobindo twice, but for a few minutes only and among several hundred disciples. The rest of the time the master would retire to his room on the first floor of a large, grey house surrounded by a flowery courtyard. This was not what I was looking for, and his method seemed too difficult for me. On the other hand I wanted to prolong my stay near the sage Ramana Maharshi. His life was public. Anyone could approach him, ask him questions and enjoy the benefits of his presence that radiated goodness, distinction and immutable peace.

And there each one of us was free to do whatever he wanted, because, with the exception of meals, there was no set of rules for community life. I got into the routine of staying for two hours each morning and each evening in the hall where around twenty people of both sexes were seated on the ground, legs crossed in silent meditation.

I read the little brochures where the main responses of the sage had been collected over the course of some thirty years. His function was to inform seekers about the nature of the ultimate reality. And I tried to see if his replies corresponded with something I felt in myself.

While reading his mail or the newspapers, correcting proofs, fanning himself or meditating, the Maharshi would sometimes look at us or would smile at the astonished children who stood there like pillars in front of him. He would often give nuts to the agile squirrels perched on the top of his sofa, and of course, his favorite cow would drop in to ask for a banana.

Morning and evening a group of Brahmins chanted the Holy Scriptures. At a fixed time the sage would take a short walk in the surrounding area, and it was on these occasions that we could speak to him in private. At eleven o’clock we would all eat in his presence, curry-rice served on banana leaves spread out on the red-tiled floor. The right hand alone was used to carry the food up to the mouth.

According to the rules of caste, the Brahmins ate apart, separated by a screen. The Maharshi was seated so as to see everyone; he had been born a Brahmin, but because he was a sage, “liberated while alive” as they say in India, he was beyond all caste observances.

The ashram was about 15 minutes from the little town of Tiruvannamalai where I had rented a tiny room for five rupees a month. At night I would unroll my sleeping bag on the terrace since my room was stifling due to the hot sun of the day. Each day I would leave the town and go to the ashram, sheltering myself from the blazing sun under a black umbrella like a well-to-do Hindu. Each day I would meditate and listen to the An Ella Maillart Photo telegraphic answers given by the sage, or else I would simply notice that some of my problems were disappearing even before I could formulate them. It was as if they were resolving themselves. I often consulted two of the disciples who knew English very well when I wanted to understand a classical text or again to clarify some statements that appeared to be contradictory.

We can never know That by which we know. However, That is the only immovable element underlying all of our changing experiences! It Is That which allows us to feel the fullness of a mysterious reality within. If we fear that the world of the senses is either going to fascinate us or disappoint us, there is no use in becoming an ascetic who renounces everything through sheer will power. But armed with patience we must, on the contrary, continue to live a normal life and at the same time inquire into the nature of this ‘I’ that surges up each time we say, “I think,” “I ask,” “I feel,” “I am.”

Meanwhile, I was reading lots of other things but they didn’t help me enough. What counted above and beyond everything else were the eyes of the Maharshi when he looked at me, a look so noble and so magnificent that one had to ask oneself what was he seeing!? So, something cracked in my heart, my thoughts stopped, and a grateful certitude accompanied by a wave of love flooded my chest. Finally I was able to love without any restriction...to love without asking for anything in return...to love for the joy of loving.

These brief and rare moments gave way to dry and critical thoughts, but they also gave me patience and courage.

All I had managed to understand was that for most Westerners, harmony, love for one’s neighbor and wisdom are inaccessible as long as the most important part of us continues to be ignored or else smothered by our secular lives which are focused solely on obtaining a security that cannot exist on the material level.

For the first time I can accept this without fighting it, because I have started to understand the absurdity of our world and the absurdity of the efforts that up to now I had blindly made to try and reach deep harmony.[1] Ella's article is printed on pages 237-242 of the 1995 edition of Golden Jubilee Souvenir

[2] Self Enquiry[1], [2].

[3] Translated by Marye Tonnaire of Tiruvannamalai.

Letters and Comments [1]

I have finished reading I Am That. It is very powerful and I liked it very much. I have subsequently started to read Talks with Ramana Maharshi every night before I sleep. It is wonderful, but sometimes I have questions relating to some of the Talks. These are practice-related questions.

Self-enquiry and Quieting the Mind

1) Bhagavan’s upadesa is “summa iru (be still)”, i.e., to quiet the mind. However, while I am doing Self-enquiry, I try to find the source of ‘I’, actively searching for it. How are quieting the mind and actively searching for the source of ‘I’ compatible? Does the latter lead to the former? Should I be doing something different?

You should actively search within for the source of the ‘I-thought’. It is like trying to find something that has been lost. When the search is relentless and one-pointed the ‘I’ that is searching dissolves into the very source it is seeking. That is the “summa iru” Bhagavan wants us to experience. The investigation by itself will bring about that perfect stillness, which is the Self. Even though we may experience grades of peace while one-pointedly seeking the source by Self-enquiry, we should not stop the investigation until the ego has merged. The ego, or individual, can never find and experience its source; it melts away or dissolves in the process of searching for it. Only then do we realize our true Self and break free from the ego-illusion. Yes, “...the latter leads to the former.”

Mental Tiredness

2) When I am trying to find the source of ‘I’, I am focusing on my awareness (devoid of any thoughts) and trying to trace it back. Of course it doesn’t get resolved and I sometimes get mentally tired. Is this the correct method? Or should I be doing something different?

This is the correct method, but Bhagavan has given instructions about overcoming mental tiredness. In the beginning, one will naturally become mentally tired in pursuing the investigation only. Often when this happens many seekers will think this method is not working, become discouraged and give up the search. That is why Bhagavan has prescribed to some disciples other methods, like chanting of strotrams, bhajans, japa and meditation. He has said that we could continue with these other forms of spiritual practices when one finds investigation too tedious. But we should always keep Self-enquiry as the center around which all these other practices revolve.

It often happens that a seeker will read about Self-enquiry, understand the directness of the method and devote him or herself to it wholeheartedly. After engaging in this practice for some time and not experiencing the desired result, they may take to other methods to focus the mind and keep it engaged in the spiritual pursuit. Then ultimately after the mind becomes one-pointed and mature, they will once again take up the method of Self-enqiury, but this time the positive effects of the practice become immediately apparent as the mind has by then become purified. Bhagavan has said that, “Those who have succeeded owe their success to perseverance.”

3) “Can jnana be lost after being once attained?’’ (This question refers to Talk 141:)

Not As One Imagines it to Be

4) What does Bhagavan mean by, “...but not as one imagines it to be. It is only as it is”?

By “not as one imagines it to be”, Bhagavan simply means that the experience of the Self is beyond imagination, beyond thought, and “it is only as it is.” So it cannot be described, imagined or known by the mind.

How to Get Rid of Vasanas

5) How to get rid of the vasanas? Is it a side effect of Self-enquiry or are there some specific practices to target reducing vasanas?

Vasanas are not a side effect of Self-enquiry. In fact, the investigation ultimately results in their extinction.

It is the old vasanas resurfacing in the present and the new vasanas that we create that binds us and obstructs Realization. Bhagavan would often mention “raga and dvesha” as obstacles to Realization. Raga is ‘attraction’ and dvesha is ‘aversion’. Both are the result of desire. If we are completely free of desire the problem is solved. No new vasanas will be formed. About the old vasanas resurfacing, we must learn to sublimate them and not allow them to fester within.

The fact is, the more you focus on your true nature, the more you dedicate yourself to the spiritual ideal and spiritual practice, the less these vasanas will manifest. Their power over you will diminish in proportion to the intensity of your spiritual aspiration and practice. Ultimately, in samadhi, all these latent tendencies will be burnt up and you will no longer identify yourself with the doer, the enjoyer, the mind and body. That will be the crown of your efforts.