50th Anniversary of Arunachala Ashrama

A Center for Daily Practice is Established in Nova Scotia

In 1972 Arunachala Ashrama branched out into Canada. Even now, understandably, we are asked, “Why did you go all the way up to Nova Scotia to open a country ashram? Couldn’t you have found a place nearer to New York City?” This question will be easier to answer if we explain a little more detail about the founder of Arunachala Ashrama, Arunachala Bhakta Bhagawat.

Bhagawat had a dream of a country ashram dedicated to the practice of the teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi where “people from Wall Street can sit on the grass.” And, certainly, he did wish that the country ashram be near New York City to make it easier for seekers of the metropolitan area to visit. But how did he go about fulfilling this dream? Much as he did in all other matters: he fixed his mind and heart on Ramana Bhagavan, surrendered at His Lotus Feet and waited for Him to bring someone to the Ashram who would make it happen.

We should keep in mind that by 1970 there was a deluge of yogis, teachers, and spiritual masters flooding into the USA, making New York City their first stop. And also at that time, masses of disillusioned youth traversed the country looking for alternative lifestyles to those of their parents. The spiritual teachers who arrived in America made disciples and opened ashrams and spiritual centers around the country that served as a haven for a good number of these youth who were often labeled ‘hippies’.

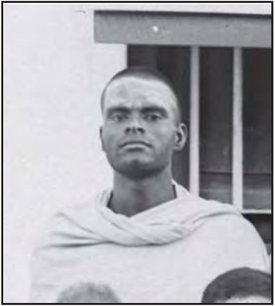

In contrast to all these famous bearded yogis in robes that attracted thousands was this penniless villager called Bhagawat, a married man who offered no initiation, no secret mantra, had no disciples, possessed absolutely no skills for organization, and who acted purely on intuition, calling himself a “servant, doorman and doormat” of the tiniest abode of his Master, Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. On top of this, the guru of Arunachala Ashrama, Sri Ramana Maharshi, had been interred 20 years earlier.

Nevertheless, the upsurge of Bhagawat’s inner, overwhelming experience of the presence of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi in his heart constantly inspired him to “Shout from the highest tower, proclaim to every corner of the earth, the glory and majesty of my Guru, Arunachala Shiva Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi Dakshinamurti!” But how was he to do it? Who was there to listen? None. So, he resorted to the confines of his Hermes 3000 typewriter to express his aspirations and experience, and thousands upon thousands of pages of “prayer manuscripts” poured out.

By 1970 or 1971, gradually, a few sincere seekers[2] began to hear his call, frequent the Ashram and receive a vibrant spark of inspiration to one-pointedly pursue the path taught and peerlessly demonstrated by Sri Ramana. Every evening the Ashram resounded with chanting followed by deep, silent meditation. Bhagawat would have already prepared a dinner to serve the devotees after the meditation. These meals, which consisted mostly of rice, dhal and potatoes, cooked in his own unique village style, were sometimes memorable to the unwary visitor who had no knowledge of Bhagawat’s fondness for chillies! It was during these after-dinner meetings that devotees came to know of Bhagawat’s desire to open a country ashram.

And in answer to his prayers, David Sewell, a young professor from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, visited the Ashram on East 6th Street in New York City during the summer of 1971. David told Bhagawat of the abundance of inexpensive farms and land available in this province of Canada. He offered to buy a property for the country Ashram there. The land prices in Nova Scotia were only 20 percent of what it would cost within a 60mile radius of New York City. A back-to-the-land movement had pushed property values up in the nearby countryside, and Bhagawat had no money anyhow.

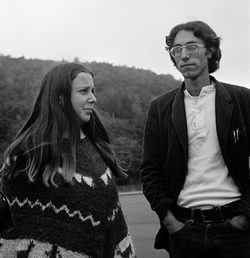

By 1971, Joan and Matthew Greenblatt, a recently married young couple, had already become dedicated to Bhagavan and the New York Ashram. They were also taken with Bhagawat’s dream of living a dedicated life of spiritual practice and service in a country setting. As soon as they heard of this offer in Nova Scotia they set off in their Volkswagen Beetle (a wedding gift) to meet David and establish a retreat for Arunachala Ashram in Nova Scotia. That was in September of 1971. Providentially, by the time the Greenblatts arrived in Nova Scotia and met with David Sewell, his circumstances had changed. Disappointed but not deterred, the Greenblatts decided to go out in search of a property themselves, even though they had no means to purchase one. Joan and Matthew had the conviction and faith that Bhagavan had brought them all the way up there for reason. So, from farm to farm, house to house, they worked their way through the province, inquiring about farms for sale from the friendliest and gentlest people they had ever met. Eventually, the search was narrowed down to the historical, idyllic Annapolis Valley, and after several days of search they found themselves returning to the home of a kind elderly couple who lived on a 130-acre farm nestled up close to the slopes of the North Mountain. This kindly couple were the Taylors, who in due course revealed to our pilgrims that, in fact, they themselves had been thinking about selling their farm and moving into town. Won over by the Taylors’ kindness and the potential that they saw in their farm as a country ashram, a price was settled upon and an agreement drawn-up and signed. This was a pure act of faith on the part of Joan and Matthew, for they did not possess, nor did the Ashram, the means to purchase it.

In March of 1972, Bhagawat, Joan, Matthew and Dennis Hartel, who had become a resident of the New York Ashram in November 1971, drove up to Nova Scotia to see the farm and make the final decision on its purchase. Nova Scotia was still cold with snow on the ground, but the warm hospitality of the Taylors and the other residents they met brightened and warmed their hearts. When gazing upon the hill behind the Ashram, Bhagawat was amazed when he saw a steep rocky outcrop near the top. “Look there!” he said excitedly, “It is right there on that cliff that I had the vision of Bhagavan standing looking down at me!” This provided Bhagawat with the certitude that the Taylor farm was the place destined to become Sri Bhagavan’s country ashram. Later, at that very same spot, a cave was discovered and was immediately christened “Virupaksha Cave”.

By April of 1972, the required funds were somehow collected and this farm of 130 acres, along with its 60foot barn and large house, was purchased in the name of Arunachala Ashrama, Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi Center for $15,000. That may not sound like much money these days, but at that time when the few devotees of the Ashram possessed nothing but their faith as collateral towards the fulfilment of a noble dream, its purchase appeared to them as nothing short of a manifestation of His Divine Will in their lives.

That very same month, Dennis, Joan and Matthew moved into the new country Arunachala Ashram in Canada. The house had been neglected, the barn had holes in its roof, the landscape around the buildings was eroded, yet none of these flaws could dampen the enthusiasm of these few sadhakas. Having traversed the

world in search of a safe harbor in which to drop their anchors and dedicate their lives to the ideal that flooded their hearts with joy, nothing outwardly could slow their march to the inner sanctuary of peace and happiness. Their outer activity was now in perfect harmony with their inner spiritual aspirations, which they understood to be the only true purpose of human existence. This filled their hearts with joy and their bodies with energy and purpose. They were building a home for the children of their guru, Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi, who had said: “By serving my devotees you are serving me.” And they experienced his guiding presence at every turn, leading them on to rest forever in the final state of pure awareness and joy.

Now, to return to the question posed in the first paragraph: “Why did you go all the way up to Nova Scotia to open a country Ashram?”

After the ashramites had settled into their new home, the advantages of a country ashram in Nova Scotia became increasingly clear. Many youth of the counter-culture movement of the late 1960s and early 70s had begun to question the focus on fulfilment in life through material gain. Among them were young people who along the way had lost sight of the value of discipline, hard work and dedication devoted to an ideal. They would float from one commune to another or from one ashram to another. To take the trouble to travel all the way up to Nova Scotia a certain amount of sincerity and genuine interest in the ideals of Arunachala Ashrama was required. Consequently, only the most earnest of seekers visited the Nova Scotia Ashram, insuring that the Ashram thus remained an oasis of deep peace and harmony.

Also, anyone who visits the pristine province of Nova Scotia, Canada immediately realizes how special and unspoiled the land and its people are. The unpolluted lakes and streams, the uninhabited natural Atlantic coastline never far from wherever one may be, the open fields, forests, farms and the softly rolling hills of the Annapolis Valley themselves are a healing balm for the ills of a restless mind.

As one dives ever-deeper into the heart of Bhagavan Ramana’s teachings, life at the Nova Scotia Ashram shines radiantly in the vast dark sky of human existence. Those who visit the Ashram with a sincere desire to deepen their experience of the Divine Presence both within and without can testify to this fact.

Concentrate on the Original Purpose

of Your Coming Here

After spending about twelve years in personal attendance on Bhagavan, I began to feel an urge to devote myself entirely to sadhana, spending my time all alone. However, I could not easily reconcile myself to the idea of giving up my personal service to Bhagavan. I had been debating the matter for some days when the answer came in a strange way.

As I entered the hall one day I heard Bhagavan explaining to others who were there that real service to him did not mean attending to his physical needs but following the essence of his teaching that is concentrating on realizing the Self. Needless to say, that automatically cleared my doubts. I therefore gave up my Ashram duties, but I then found it hard to decide how in fact I should spend the entire day in search of Realization. I referred the matter to Bhagavan and he advised me to make Self-enquiry my final aim but to practise Self-enquiry, meditation, japa and recitation of scripture turn by turn, changing over from one to another as and when I found the one I was doing irksome or difficult. In course of time, he said, the sadhana would become stabilised in Self-enquiry or pure Consciousness or Realization.

From my personal experience, as well as from that of others within my knowledge, I can say that before recommending any path to an aspirant Bhagavan would first find out from him what aspect or form or path he was naturally drawn to and then recommend him to follow it. He would sometimes endorse the traditional stages of sadhana, advancing from worship (puja) to incantation (japa), then to meditation (dhyana), and finally to Self-enquiry (vichara). However, he also used to say that continuous and rigorous practice of any one of these methods was adequate in itself to lead to Realization. Thus, for instance, when one adopts the method of worship, say of the Shakti, one should, by constant practice and concentration, be able to see the Shakti everywhere and always and in everything and thus give up identification with the ego. Similarly, with japa. By constant and continuous repetition of a mantra one gets merged in it and loses all sense of separate individuality. In dhyana again, in constant meditation, with bhavana or deep feeling, one attains the state of Bhavanatheeta, which is only another name for pure Consciousness. Thus, any method, if taken earnestly and practised unremittingly, will result in elimination of the ‘I’ and lead to the goal of Realization.

Once some awkward problems concerning the Ashram management cropped up. Without being directly concerned, I was worried about them, as I felt that failure to solve them satisfactorily would impair the good name of the Ashram. One day two or three devotees went to Bhagavan and put the problems before him. I happened to enter the hall while they were talking about them, and he immediately turned to me and asked me why I had come in at this time and why I was interesting myself in such matters. I did not grasp the meaning of his question, so Bhagavan explained that a person should occupy himself only with that purpose with which he had originally come to the Ashram and then asked me what my original purpose had been. I replied, “To receive Bhagavan’s Grace.” So, he said, “Then occupy yourself with that only.” He further continued by asking me whether I had any interest in matters concerning the Ashram management when I first came here. On my replying that I had not, he added, “Then concentrate on the original purpose of your coming here.”

His Eyes Are the Windows

of Everlasting Spirit

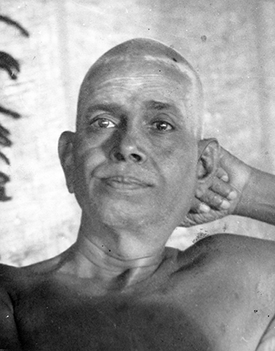

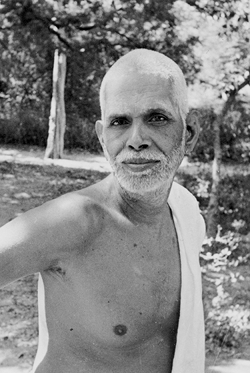

I felt a divine peace, a glory of stillness. So calm, so still, Bhagavan Sri Ramana sits, this sage of Arunachalam; a little, pale gold ivory figure, with a slim, aged, feeble body, and the face of a child. But the eyes are the most remarkable feature of his face.

His eyes are the windows of everlasting spirit. They show the shining calm of the God within its delicate shell, clear, wide open, gentle, candid eyes; yet deep seeing into the self within — innocent, yet understanding; all compassionate, yet thoroughly weighing and understanding the play of life.

At times these eyes rest in mild scrutiny on the people around, singling out for a moment one or another of the crowd, then pass on with complete detachment, yet, with a gentle withdrawal, a patient wish to make others content. Sometimes in deep thought he sits; chin resting on hand, the spirit withdrawn to unknown heights. Sometimes in a gentle soft voice he speaks a few words to someone whose thought calls his attention.

Aloof, alone, what has this silent abstracted man to give to others? The fact that there are others around him proves that he has something to give. The heart and spirit of man ever seeking solace and the remembrance of its birthright alone can answer this question. And the answer comes in as many different ways as there are people who visit this centre of spiritual power. Each gets that thought to which he is attuned. These are the thoughts I got, seated on the floor, in that quiet room presided over by that silent figure.

Ella Maillart of Switzerland

Part II

We express our sincere gratitude to Aine Keenan for generously sharing all her research on Ella Mailart and Marye Tonnaire both of Sri Ramanasramam - who enthusiastically provided us with a smooth and concise English translation of Ella’s French interview and the last chapter of her book "Croisieres et Caravanes".

In our last issue, in the article “The Cat on Bhagavan’s Couch”, we introduced an exceptional personality of the 20th Century who had taken refuge in India from 1940 to 1945, while the Second World War raged through most of Europe and Asia.

This was Ella Maillart, an early pioneer among women adventurers, strong, ever-curious about the unknown and fascinated with travel. She had written a half dozen books about her travels and another series of books has been published about her since her passing in 1997 at the ripe age of 93.

After she left India and returned to Switzerland, Ella settled into a mountain chalet high in the Alps and named it “Achala”, abbreviated from Arunachala.

Wherever she traveled throughout her long life she took photos, notes and even films. These chronicles of life in some of the most remote regions of the world have been recognized as valuable historical documents, and her fearless spirit of adventure inspired women and men around the world.

While at Ramanasramam in 1942 she wrote Cruises and Caravans; though autobiographical, the book primarily chronicles her 1935, 3,500-mile trip west from Peking through the Taklamakan desert and Sin-kiang (at that time closed to foreigners) to Kashmir: a journey which took seven months. While in Tiruvannamalai she received a copy of the book from the publisher, which she immediately showed to Bhagavan, a happening that we described in our last issue. Ella later formally presented the book to the Maharshi with the following inscription:

Dear Bhagavan,

Here is the book you helped me to write the summer before last. It is a ‘war production’ intended for young readers, and you may remember that the publishers sent me, as a sample for that series, the book by the mountaineer named Smythe.

Once more I form the deep wish that after so many years of dealing with the external world – as you may see by glancing through my autobiography – I shall now make swift progress in discovering the inner life leading to You.

Yours – Ella

Sri Ramanasramam, 9-2-43

With the publication of this book, Ella’s financial situation improved and a career as a writer, lecturer and travel guide appears to have been established, though she did not leave India for another two years. The book was also later published in French. In the French edition she added one more chapter in which she shared with the public her spiritual journey, a journey that began in her youth but ended at the feet of the Sage of Arunachala.

In a French-filmed interview [1] at her Swiss Alps chalet in 1973, Ella talks about her time with the Maharshi “During this time I was thinking of the war in Europe, and with feelings of despair, I felt pressed forward to go to this Sage whose address I already had.”

Holding in his hand one of the photos Ella had taken of Bhagavan, the interviewer asked her if this was the first sadhu she had met. Ella, in general terms, explained to the interviewer what a sadhu is:

“A sadhu is a master who has found the truth; he is not looking for it, and all of his answers come from an inconceivable level of consciousness. Never would any of us reply as he did to all the varieties of questions that one would ask him. I decided to stay with him for quite a long time and then, after two years, I stayed with another master, another sage who was in Kerala (Krishna Menon) and who taught the same method of introspection – “Know Yourself”. Try to know who is the true Self, the ‘I’ – with a capital ‘I’ – and not the little ego. And in Kerala I also stayed a very long time, more or less until the end of the war.”

Then the interviewer, apparently a little puzzled, asked what were the questions to ask a sage and what it meant to live with a sage. Ella went on explaining, “Well, the basic question I asked myself since my childhood when I would see something while living at the Creux de Genthod (name of the place where she lived near Geneva) was: ‘What is Reality, the center, the essence of what we see; the essence of life in the present moment?’

“I knew that the present is the only ‘Real’ thing, but then again it’s just a word used to give a response. Well, with that understanding, when we want to get to the bottom of a problem, we have to know who we are, because everything depends on me. I am the one who is conscious and who sees things. And all the questions that one asks a sage revolve around that one fundamental question, ‘Who Am I?’ Who is the Real I? All of the wisdom in the whole world speaks of two ‘I’s’, a little ‘i’ who is identified with the body and an ‘I’ who refers to the Supreme ‘I’. And it is necessary that the two ‘I’s’ coalesce to form only one (merge into one), so that we are not perpetually divided in ourselves. And the true Master is one who has accomplished this Realization directly, the direct experience of the True ‘I’. He is capable of responding to our questions in such a satisfying manner that we say, ‘Voila! He is a Master,’ I understand his responses, I like the way he responds, and I will stay close to him to progress and refine myself so that I too will be able to reach his level of consciousness, if that is my destiny.

“So we stay close to such a sage, though most of the time he may respond in silence, without saying a word, by a kind of telepathy. And most of the time he foresees our questions. He gives us books, he helps us with readings, and we can ask questions when we have not understood something. And it’s this inner work that is worthwhile. Then we become so passionate about what we find within ourselves that we accept all the difficulties of living there in the extreme heat with unsuitable food and crude accommodations.”

Then the interviewer asked whether she succeeded in coalescing the two ‘I’s and, if so, why did she return to Switzerland rather than stay in India.

Ella: “Well, you speak of the supreme goal as if it were very easy to obtain. I think that I understood (the concepts), and equally the techniques that they gave me. And if I actually did understand something worthwhile, I should be able to put it into practice as well here (in Switzerland) as over there. The climate there is something really extreme and the food didn't agree with me at all. And I think if one is born in a certain place, it is in that place one must accomplish one’s life and one’s destiny But I went back many times to the Sage (The Maharshi), up until his death. After the war I went back three or four times and in 1951, I spent four or five months....”

These visits to the Ashram that Ella mentioned in this interview do not seem to have been recorded earlier. She may have also visited Krishna Menon (>Atmananda) in Kerala, with whom she had spent considerable time during the war years. He passed away only in 1959. He had no formal ashram and lived with his family in their Trivandrum home.

In the interview, filmed in her chalet study, two photos, the Welling bust photo of Sri Ramana and one that she herself had taken of Bhagavan, are prominent. By all evidence it was the Maharshi whom she connected with and revered most, and it was his teaching she practiced throughout her long life.

In the course of Ella’s natural, spiritual maturing process, which no doubt was accelerated in the Maharshi’s proximity, her relentless restlessness subsided with the realization that “The world with its countless aspects cannot give us the fundamental answer: only God can. And God can be met nowhere but in ourselves . . .” So when she returned to Switzerland in 1945 Ella settled down to a quiet life, though her fame continued to grow from day to day. A glimpse at the Index of Ella’s Geneva Archives reveals a prolific correspondence with renowned writers, thinkers and political figures of the 20th Century, including Winston Churchill, Teillard de Chardin, Alexandra David-Neel, Arnaud Desjardins, André Dupré, Olga Tolstoy, Titus Burkardt, Krishna Menon, Edwina Mountbatten, Pierre, Prince of Greece, to name a few. A little closer to home, the archives have folders of correspondence between Ella and Chinnaswami, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Major Chadwick, Guy Hague, Henri Hartung, Wolter Keers, Jawaharlal Nehru, Ethel Merston, and Swami Siddheswarananda.