Munagala Venkataramaiah

and the Making of Talks[1]

In a very critical and distressing period of his life, a humble devotee sought the presence of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi for his own peace of mind, and lived in the Ashram with the kind permission of the Sarvadhikari, Sri Niranjanananda Swami. The seeker took it upon himself to note down, as occasions arose, the sweet, refreshing and enlightening words of the Master. This self-imposed task was undertaken for the purification of his own mind and better understanding of the subtle and profound words of Sri Bhagavan.

The foregoing anonymously written lines preface the early editions of Talks which, for many, stands as one of the greatest collections ever compiled about Bhagavan. Talks not only excels in its capacity to faithfully document over a sustained period the actual encounters between Bhagavan and devotees in the Hall but its prose is smooth and readable, rendering accessible what might otherwise have been difficult-to-understand phrases and instructions. The editor’s commentary sets the stage and contextualizes the atmosphere of the moment for each of the recorded dialogues. As the recorder and translator had an intuitive grasp of Bhagavan’s teaching — not to mention proficiency in the relevant languages (Tamiḷ, Sanskrit, English and Telugu) and the natural gift for translation — he was able to perceive and transmit the subtler features of Bhagavan’s responses to visitors’ queries, and thus provide the comprehensive presentation of Bhagavan’s teaching that we find in this remarkable book.

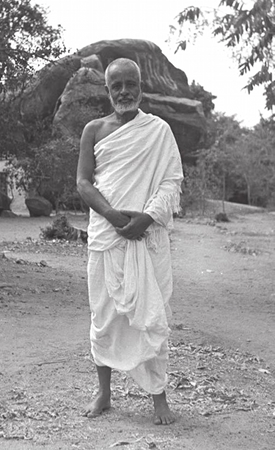

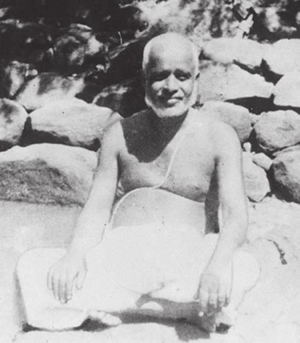

If it weren’t for Major Chadwick, posterity may not have known who the driving force behind this great book ever was, for the name “Munagala S.Venkataramiah” is nowhere to be found in the early editions of Talks. It seems that the responsible party had chosen to remain out of view and thus refers to himself only as “The Recorder”. In the following pages we will take a brief look at the life of “The Recorder”, Munagala S. Venkataramiah, (later Swami Ramanananda Saraswati), and at the circumstances that led to the production of one of the twentieth century’s great spiritual texts.

Munagala S.Venkataramiah was born near to Bhagavan, both in time and space, in Cholavandan of Madurai District in 1882. He was the only one of Munagala Subramanian’s five sons not to study in the patasala of Cholavandan, but instead took up studies in the English school. One day in 1896 he came home from school and told his mother about a young Brahmin boy from the neighbouring school who had run away and was no more to be seen. Little did he know that the boy in question would one day become his guru. [2]

At the tender age of thirteen, Venkataramiah and his uncle’s daughter were married. Venkataramiah devoted himself to his studies and later joined Madras Christian College before going to Bombay for further studies at a laboratory there. By the age of 18, the couple had their first child at which time Venkataramiah returned to Madras for examinations. Standing first in the Madras Presidency and having received the Ami Gold Medal, job opportunities abounded and he was privileged to join Noble College as a lecturer in chemistry.

He lectured at various colleges in the decade that followed until one day in 1918 tragedy struck with the sudden death of his daughter. Venkataramiah was so grief-stricken that he had trouble maintaining his professional duties. It was during these years that he took up a formal study of the Upanishads, the Gita and the Brahma Sutras and maintained contact with Sri Sai Baba Narayan Guru, a Bengali sadhu and a disciple of the famous Kali Kamliwala of Hardwar, who set him on the spiritual way. It was also at this time, 1918, that he first came to Skandasramam and met Sri Bhagavan.

As he worked through the trauma of family loss, he was transferred to Ooty to work as a chemist with the Madras Government in the Department of Small Industries which, while providing new environs from which to make a new start in life, carried with it the disadvantage of being geographically isolated from the Bengali sadhu who had been such a help to him. But two years later he was made the Superintendent of the Government Industrial Institute in Washermanpet (Chennai), which brought him back into close proximity with Sri Sai Baba Narayan Guru. This notwithstanding, the connection was short-lived: just two years later, 1922, his guru left the body.

In the years that followed, Venkataramiah used his spare time to study works on Advaita Vedanta. As he had studied English and Latin in his youth and was not well-versed in Sanskrit, he now took it upon himself to take up a formal study of the ancient language to facilitate a better understanding of these great works. In 1927, a little more matured not only by virtue of his involvement with formal advaitic teaching but by ten additional years of life’s vicissitudes, he made his second visit to Sri Bhagavan. From the time of this meeting, he began coming with his family each summer to spend a month at the Ashram with Bhagavan. Five years passed this way until 1932, when trouble struck once again: without notice, Venkataramiah lost his position of employment. With a daughter yet to be married off and young sons yet to be educated, Venkataramiah found himself penniless, without work, and without any hope of getting work: it seemed that fate had dealt him its worst blow.

It was in this fragile period that he finally took refuge in Bhagavan and came to the Ashram as an inmate, placing all his cares at the Master’s feet. And it was in this ‘distressing period of his life’ that he took up the project of recording the conversations in the darshan hall each day, bringing with him not only his training in disparate languages and his wide reading in advaita but the keen and eager listening that comes with a searching heart.

After he lost his teaching position in 1932, Munagala S. Venkataramiah became a regular inmate of the Ashram. When devotees learned what had happened, Grant Duff, a family relation of the then Governor of Madras, stepped forward and offered to intercede on Munagala’s behalf in order that the injustice done him might be set right. A petition was filed in Madras and was sure to have been decided in Venkataramiah’s favour, assuring the reinstatement of his post, had it made it to the Governor’s desk. But as it turned out, the Governor went on leave and the one appointed as acting Governor was none other than the man responsible for the unfair treatment in the first place. Needless to say the petition was dismissed and Venkataramiah’s fate took another course.

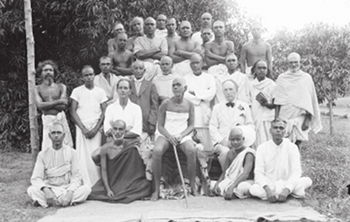

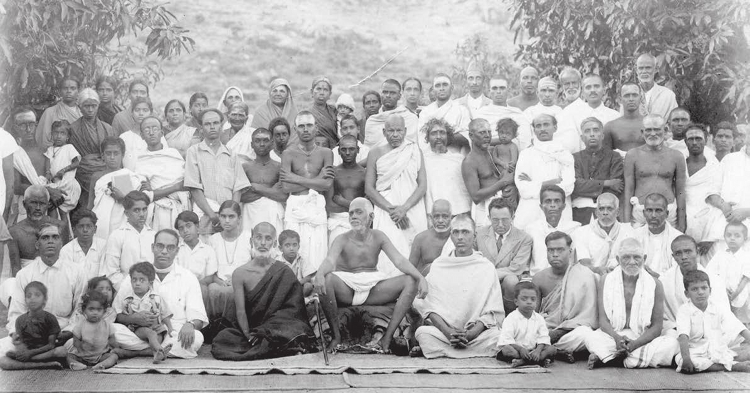

Though financially insolvent, Venkataramiah had the consolation of sitting at the feet of Bhagavan each day. He also had the good fortune to take up Ashram work and answer letters sent by out-of-state devotees. Acquainted with Tamiḷ, Telugu, English and Sanskrit, and having formal experience in translation, he was also called upon to serve as translator in the hall.

In January 1935, Venkataramiah began making entries in a notebook while sitting in Sri Bhagavan’s presence. In time, the practice of committing to paper the interactions that took place between devotees and Sri Bhagavan became for him a fervid sadhana and he took great care to faithfully record all he heard.

When perusing the notebook’s carefully annotated entries, one gets a feel for the passage of time, the numerous sincere seekers who came before Sri Bhagavan and the weightiness of what went on between them. Indeed these pages are the minutes of life-changing encounters between seekers deeply longing for a meaningful change in their lives — the recorder among them — and the Master, ever ready to dispense the requisite spiritual medicine.

On occasion non-native visitors wrote their questions down on paper in advance and presented them to Venkataramiah, either to be read aloud to Bhagavan or to be translated into Tamiḷ and then read out to Bhagavan. Some pre-written questions have been pasted onto the pages of the notebook and beneath them, Munagala’s transcription of Bhagavan’s response and the conversation that followed.

The recorder retained key Sanskrit words and phrases and transcribed Sanskrit and Tamiḷ slokas and verses in the original. In some cases, Bhagavan’s responses were noted down word for word in Tamiḷ providing present-day devotees with authentic samples of Bhagavan’s spoken Tamiḷ. This is significant when one considers the remarkable fact that, with the exception of a few brief passages in A. Devaraja Mudaliar’s chronicles, the Ashram literary corpus contains next to no transcriptions of Bhagavan’s spoken Tamiḷ.

For the most part the transcriber translated conversations into English extempore, writing them down as they occurred. On other occasions, when silence prevailed in the hall, he would narrate the details of the moment, outline the scene and give descriptions pertaining to the actions of those gathered as well as delineate features pertaining to their characters, appearance, state of mind, etc. His observations would invariably set the stage for the discussion to follow and his knack for illustration readily captured the stimulating atmosphere of the hall, giving the reader the flavour of what it would have been like to be in Sri Bhagavan’s presence in those years.

A number of entries suggest that there were occasions when Venkataramiah was, for whatever reason, unable to record immediately the goings-on in the hall but only later summarized them by recollection. In some cases when Bhagavan replied in Malayalam or a language unfamiliar to Venkataramiah, the recorder would have to rely on subsequent summaries from native speakers. On other occasions, when dialogues took place outside the hall, such as on the Hill during Bhagavan’s afternoon walk (e.g. Talks §225), Venkataramiah would jot down a synopsis given by an attendant or another devotee who was present.

In the same year Venkataramiah began his recording, Maurice Frydman, the Polish engineer-inventor, translator and editor came to the Ashram and spent a good deal of time in the hall. He proved to be an engaging interlocutor and a number of his questions with Bhagavan’s replies are included in Talks (e.g. §74, §115, §158, §179, §182...). In 1936, with Munagala Venkataramiah’s permission, Frydman made use of his formidable editing skills, went through the notebooks and made selections from the available entries. These he edited and compiled into a small volume that was to become a modern advaitic classic. Maharshi’s Gospel was published three years later on the occasion of Bhagavan’s 60th Jayanthi in 1939 and was immediately popular with devotees. Readers found their doubts and questions evaporate by Bhagavan’s unique way of moving straight to the heart of the question in a way that dissolved the question altogether, sidestepping any extraneous conjecture. Bhagavan seemed to mirror the insights of the Upanishads simply by his presence but when pressed, he could speak to knotty philosophical problems and onerous spiritual vexations in plain terms, and in a manner that even the uninitiated could grasp. Alas, devotees would have to wait another fifteen years before the remaining entries would make it into print. But all in good time.

By Bhagavan’s bountiful grace and Munagala’s nimble hand, the notebook entries continued. Excepting some variation in sequencing, the handwritten notebooks reflect what we know today as Talks and nowhere is there any indication that entries were omitted, discarded or lost. However, time gaps appear — some a few days at a stretch and others for longer periods. The entry for June 12th, 1937 (Talks §426-27), for example, is followed by an entry dated December 15th (Talks §428), a full six months later. Was Venkataramiah away during these months or otherwise ill-disposed? There is no way of knowing for certain though in general, entries during the summer months were sparse, and thus would suggest that the recorder may have spent portions of the year elsewhere.

The journal logs continue until 1st April, 1939, when a final entry was made (Talk §653). Sometime after this Venkataramiah handed the notebooks over to the Ashram for safekeeping and, as far as we know, made no further diary entries in the hall.

Not long after this, Devaraja Mudaliar settled in the Ashram and began his own chronicles which were serialized in the Call Divine and later published by the Ashram under the titles ">My Recollections of Bhagavan Sri Ramana (1960) and Day by Day with Bhagavan (1968). Suri Nagamma also began chronicling daily life at the Ashram in 1945 and published two volumes titled Letters from Sri Ramanasramam (1969) and later, a third volume, Letters and Recollections from Sri Ramanasramam (1979).

Venkataramiah left the Ashram in 1952 after Bhagavan’s Mahanirvana but returned two years later. After recovering from a heart attack, he received sannyasa diksha and took the name Swami Ramanananda Saraswati. He then helped with compiling and editing the notebooks he had maintained twenty years earlier, the entirety of which were published in three volumes in 1955.

I went to Calcutta, met Sri Sankaracharya Krishnabodhasramji of Badrinath and had his sannyasa sanctioned. In 1959 he returned to the Ashram — not to leave Tiruvannamalai again — and continued his translation work which eventually yielded a number of Ashram publications, i.e. Tripura Rahasya, Advaita Bodha Deepika, Kaivalya Navaneeta and Arunachala Mahatmyam, among others.

Ini retrospect, when one considers the spiritual and literary sway of Talks, one can be thankful that Venkataramiah lost his teaching post and was compelled to take refuge in Bhagavan in that ‘distressing period of his life’. What may have at the time looked like ill-luck turned out to be a great boon, both for Munagala Venkataramiah, who would be graced to sit at the Master’s feet and imbibe his words and silence on a daily basis, but also for countless devotees who over the decades would have the opportunity to encounter Bhagvan’s teaching in its purest form, made accessible and free of superfluity, faithfully pointing the reader toward the goal in such a way as few publications then or since would be able to do. By virtue of one man’s diligence in the hall 75 years ago, we find in Talks the direct path set forth in clear, straightforward language, a message that promises nothing less than transforming the lives of all who would partake of it.

February, 1963

Munagala S. Venkataramiah was absorbed into Bhagavan in Tiruvannamalai.

[1] Reproduced from the July and August 2012 issues of Sri Ramanasramam's Saranāgatī newsletter)

[2] For biographical details, see M.V.Krishnan’s article in the Mountain Path April, 1979, pp. 97-99.