Nadhia Sutara

In Profile: Mar 2022 issue Saranāgatī

Coming to Arunachala in the early 1980s, Nadhia worked for several years on 'The Mountain Path', and over the decades made an impression on her peers by virtue of her honesty, forthrightness, and transparency as well as her courage, humour and acceptance of all those she met. Drawing from published writings, personal correspondence and sharing with friends and family, the following is a brief account of her years at Arunachala spanning four decades until her untimely demise just a few days after her 72nd birthday in early August of last year.

Born 01 August 1949 to Jewish parents[1] in New York City, Nadhia Sutara (née Susan Teicher) was the eldest of three children. She grew up with multiple health issues, not least of all, severe allergies which impaired her ability to digest food. From an early age, she depended on a special diet. Her vision was also impaired, and she was said to have difficulty making friends because, with limited eyesight, ‘she wasn’t sure who was in front of her’ at any given time.

To top it off, childhood abuse brought mental health issues that plagued her teen years. Doctors were brought in, but progress was slow. The family was not actively religious, and Nadhia stood out in seeking solace for her early life trauma through spirituality rather than assistance in any formal medical or therapeutic setting:

I still had only one absolute certainty: that I did NOT need a psychiatrist. There were several in my family, and they were all as clueless as I was... Having a devotional temperament and an iṣṭa-devatā from [an early age], it was devotion to this ishtadevata that carried me through the darkest days of my life until one day I realised that [what I needed was] a spiritual teacher. So, I sought one out and became a serious sadhaka.[2]

At the age of 18, Nadhia found a spiritual teacher who helped her:

Once the teacher was regressing us, asking us to ‘see’ snapshots of when we were ever younger and younger and then before we were born. Suddenly I realized (and the thrill is with me even now) that ALL happens within me. I never move. The body is WITHIN me. Clearly the me of that experience was not the conventional ‘I’ or even sphurana. It was just one experience, [but] it changed my life.[3]

By her 30th year, however, this fruitful relationship dissolved. Though she had no Russian blood in her family lineage, she felt called to study Russian[3a] and found a mentor in her high school Russian teacher. She pursued Russian studies in her undergraduate years at NYU. Despite the richness and depth of her Jewish heritage, she felt called to convert to the Russian Orthodox Church and revelled in its extended Slavonic liturgies. She also sometimes attended St. Aloysius Roman Catholic Church in her native Great Neck, the region on Long Island where she grew up, bordering with Queens. She went on to do an M.A. in Russian literature at Columbia University. She recounted that when she took her final exam, she opened the exam paper and discovered she couldn’t answer a single question. Looking round the room she saw from the panicked expressions on everyone’s faces that the others seemed to be in the same position. Not willing to write nothing, she was bold enough to write at the top of her paper, ‘I have done years of research and study of Russian literature but none of the information I have accumulated is useful in answering these questions. So, instead of displaying my ignorance of the set questions, I will display my knowledge of Russian literature by answering the following questions.’ She then went on to invent her own exam questions and wrote about them. She passed the exam.[4]

In 1979, at the age of 30, she found herself at a crossroad. Uncertain about what to do next, she took a 9-hour bus ride to upstate New York to the Rochester Zen Center to seek the advice of Roshi Philip Kapleau. She had never met him or even corresponded with him, but ‘knew’ she was guided to seek his counsel. After listening to her for some time, Kapleau casually commented, ‘You know, some people in your position go out and travel.’[5]

Starting Out

The words resonated and Nadhia knew what she had to do. She returned home and made preparations to travel to India. She may or may not have known it then, but Roshi Kapleau had a karmic affinity with Arunachala. His daughter was a Bhagavan devotee and had visited the Ashram numerous times. Like the Roshi’s daughter, Nadhia set her sights on Tiruvannamalai:

When I finally arrived at Arunachala, it was literally love at first sight, and I found myself making my first spontaneous, wholehearted act of surrender. As I climbed the slopes behind the Ashram for the first time, I was so overwhelmed by the power of the sacred Mountain that my Ishta merged in It and I found myself falling to my knees and praying: ‘If I live or die, if I go mad, whatsoever happens, I surrender it all to you, O Arunachala!’[6]

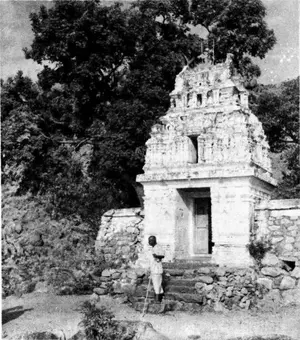

Nadhia arrived in the early 1980s. After a stay at Morvi Guest House, Nadhia moved up onto the Hill just about the time Swami Ramanananda (Seshadri) vacated Bhagavan’s Mother’s room at Skandasramam. Nadhia took up residence in the same room for a time before shifting to Guhai Namasivaya Mantapam: Within a few months of arriving, I was living on the Mountain, and this first act of surrender became, in essence, surrender to life itself as it unfolded while I lived on the Mountain[7] ... I was living in Guhai Namasivaya Kovil. Everything was very sparse and spartan in those days: very few tourists, and then only during the winter months; only about ten Westerners were living in Tiruvannamalai at the time.[8]

She had a rather central location, just slightly down the Hill from Virupaksha Cave. Of course, this is the same temple where Keerai Patti had lived all those years earlier during the period when Bhagavan was living on the Hill. Invariably people came to visit Nadhia, not least of all, because her abode had been home to the legendary 16th-century Virasaivite[9] yogi-saint, Guhai Namasivaya. Regular Western pilgrims coming to India, following the trends of the time, also came to see her, and in some cases, tried to tempt her away from her new-found paradise:

People used to visit occasionally and tell me that J. Krishnamurti or Anandamayi Ma were in Chennai, or Sai Baba was in Puttaparti, and so on. Ammachi personally invited me to come with her to her ashram in Kerala and be her disciple. Everybody was recruiting, it seemed, and my peers were running around looking for someone to hand them the ‘Truth’, Enlightenment, or whatever they imagined their goal to be. I found this perpetual frenzy confusing but was saved by reading a line in Sri Ramana’s Talks, where he says: “Attend to the purpose for which you have come.” It rang so true that I stayed where I was, and everything I needed did indeed come to me. Thus, this teaching of Sri Bhagavan became my guiding principle. I referred to it again and again as events cropped up, and it always stood me in good stead.[10]

Entering the compound through a gopuram on the eastern side, Nadhia made use of the spring of fresh water next to Guhai Namasivaya’s cave. She found the mantapam spacious and it provided her with a protected environment, well-suited to the work she was about to undertake. Sadhus resided in caves and grottos nearby, including two Westerners, Therese Rigos, the retired French dentist who had formerly been close to the Pondicherry Mother, and the Australian, Narikutti Swami, an architect, who had come via Sri Lanka, where he had been a disciple of Yogaswami.[11]

All was well. Or so it seemed. But soon enough, trouble struck:

Shortly after I’d moved into Guhai Namasivaya mantapam, I became ill. Somehow the word got out and one day, Therese walked into the compound. She took one look at me and said in her typically joyous voice, ‘Oh! You have jaundice!’ in the same tone as one might say, ‘Merry Christmas!’ She then approached me, introduced herself and read me the Riot Act: she forbade me from leaving the compound until all the yellow had gone from my eyes and skin. She promised to bring me a lot of fresh fruit to eat — oranges, sweet limes, etc — to help counteract the bile and keep me from having to go out to shop. She also went down to the Ashram every week to bring me back spiritual books to read. Despite her lack of money, she never failed in this, even providing a huge clutch of green coconuts for me to drink every day. It took two months for the yellow tint to depart completely. Therese then announced me cured and went back to her solitary life.[12]

Nadhia learned Tamil while on the Hill. As she had no income, she lived on a meagre diet. If she was naïve in respect of the spiritual practices of South India when she arrived, she got help in basic meditation from Maniswami, the caretaker of Virupaksha Cave, and other swamis living on the Hill. Nadhia’s inquisitive mind led her into the heart of the teaching through books on and about Sri Ramana and she took them to heart and set about repairing injuries from the past:

I needed to deal with a seemingly endless mass of seriously negative vasanas that had no intention of surrendering to anything or anyone and fought back by creating crippling migraine headaches whenever I tried to meditate. I had by then learned about Bhagavan’s Self-enquiry, but I had a problem because I was unable to grasp in practice what he had meant. The fact was, I had no experience of an underlying permanent ‘I’.[13]

As for her friend, Therese, ever the hermit, she continued to remain aloof and could not be counted on for any ongoing advice. But one day Therese came to visit Nadhia at Guhai Namasivaya:

Therese came to tell me that the Mango Tree swami, Subramaniam, had died and his sadhu funeral would be held that day. She explained to me that it is considered a sacred obligation to attend the funeral of anybody one had known, despite one’s feelings for or against them. So, I prepared to go. Maniswami who was the most spiritually educated of us all, conducted the proceedings and he was already there arranging things when I showed up. The first thing I noticed besides the order that Maniswami immediately brought to the situation was the Silence. I had never been near a just-deceased person before in my life, not to mention a sadhu, and the palpably thick spiritual Silence impressed me profoundly. It has been my experience ever since that time that some mysterious blessing lingers around the recently deceased, especially if they have lived a spiritual life and not died in fear. What a difference to your garden variety Western funeral. First, nobody was sad or crying, and it had nothing to do with the fact that Subramaniam Swami had managed to antagonize or alienate almost everybody who knew him except Therese. He was dying of TB and gasping for breath for many days before he expired. He refused to go to the hospital where he could have been given oxygen to ease his suffering. No, he wanted to end his life on his beloved Arunachala. So, with every breath he would gasp, ‘Arunachala! Arunachala!’ until the last breath.[14]

Nadhia continues:

Later, when I read how Ramana Maharshi always found something good to say about a departed soul, I remembered how we all marvelled at Mango Tree Swami’s fortitude and determination in refusing all comfort and dying with his Ishta’s name on his lips with every single breath until the last. Truly, we never knew him until the day of his death, when we learned how profound his devotion had been![15]

The funeral wake took place at Mango Tree Cave where Subramaniam had resided but as per tradition, interment should not take place on the Hill itself but down below in the burial ground:

The men took Swami’s freshly washed and clothed body to be buried. Therese, Narikutti Swami and I stayed behind at Therese’s hut (Mango Tree Cave’s former kitchen room) and, over tea and biscuits, discussed what we wanted done with our bodies if we were lucky enough to die here. Narikutti Swami mentioned that he wanted to die sitting up in meditation. Therese said that she had heard that cremation was painful and stated that she wanted to be buried. She mentioned that in addition to her Hindu leanings, she was also deeply attuned to Christianity. She was indeed quite psychic. She mentioned that upon the death of her father, who had no religious or spiritual leanings whatsoever, he came to her and complained that nobody he had visited after his demise had understood that he was there. Only Therese did, and they spent a few days talking so that he could move on in peace and harmony. [As for me], I firmly stated that I wanted to die with Arunachala’s name on my lips and be cremated without fuss or delay.[16]

The Tapasvin Tradition

Years on the Hill provided Nadhia with first-hand training in the life of renunciation. Her seclusion allowed her to work through the misgivings of her youth and she took refuge in Bhagavan Ramana’s teaching, not least of all, in Self-inquiry. She was presented with an approach to religious practice unlike anything she had experienced in her native North America. Till then, she had seen religious people engage their faith in a merely formalistic way without taking the risk to put their hearts on the line, and how their faith seemed to be a merely rational preoccupation. But in Tamil Nadu, she learned that religious faith has as its singular purpose to lead the seeker out from suffering to transform their lives:

Organised religion does not provide for enquiry into the profound truths behind the dogmas upon which their faith is built... While faith and surrender are the Path, if one remains at this stage — believing rather than understanding — and turning someone else’s experience (Bhagavan’s for instance) into ‘unchewed’ blind faith, they remain at the stage of religion, which of course has its purpose but is not an end in itself. There is also a great risk of killing the teaching in oneself, making it into an intellectual, hardened conceptual understanding, incapable of modification, even preventing further experience. Sri Bhagavan’s teachings, for example, are intended to take the mind beyond itself, not further burden it with more thoughts. A conceptual understanding can become so complete that it becomes a jail; and rather than modify one’s understanding of the initial teaching through continual reflection (manana), one throws away what experience may come as invalid — so unfortunate! — and continue to construct a conceptual bunker leading from the ‘ground floor’ of ignorance to an imaginary ‘roof ’ of enlightenment. A great tragedy.[17]

Nadhia began to see that the tapasvins that had lived on the Hill, not least of all, Bhagavan Ramana, embodied the understanding that faith, worship and surrender are deeply personal matters and that any valid spiritual undertaking begins in one’s own heart with direct experience:

How does this teaching apply to me? Can I find some application for [it] in my life? Can I hold it up as a mirror to guide me? If not, what in me is blocking my understanding? If I do not yet understand it, let me keep it on a handy shelf in my mind in case something comes up to illuminate it. Then I can reflect upon it further.[18]

Her near decade-long apprenticeship on Arunachala, however, would not last indefinitely. She narrates:

Things shifted for the three of us western mountain cave-dwellers in 1990. There had been a general amnesty for hardened criminals when the new Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu had been elected, and the Mountain became seriously unsafe for anybody. Slowly, each of us left. I was invited to live and work in Sri Ramanasramam; Therese went to join her husband, Richard, who was having heart problems. From there they would only visit their three places on the Mountain (Richard and Therese had found another cave on the other side of the Mountain) when Richard’s health permitted; and Narikutti, after harsh treatment at the hands of a thief who believed he had money in his cave, moved into Seshadri Ashram.[19]

Now living at the foot of the Mountain amidst society, the change of lifestyle affected Nadhia at first and she would later recall her years on the Hill as ‘the happiest days’ of her life.[20] But soon she found herself doing work that she loved. Having had abundant experience editing, writing and translating before coming to India, she began to assist V. Ganesan, the then editor of The Mountain Path in editing. She wrote articles and proofed the magazine. This work suited her, and she adjusted to life off the Hill, having now given up her solitude.

She travelled to North India and spent time in Lucknow before returning to Tiruvannamalai. By the mid-1990s, however, after nearly fifteen years in India, Nadhia’s life-long frailty with respect to food-intake caught up with her and her bodyweight dipped dangerously low. Food would go through her whole GI tract without breaking down and being absorbed. She hovered around 91 pounds and said her main ambition physically was to ‘become a 98-pound weakling’. Her doctors warned her that she had to stay above 85 lbs since that was the point where she would start getting irreversible damage to her organs. Finally, she had no choice but to return to the West. In the days leading up to her flight, she required intravenous fluids.

Once back in North America, her body got a chance to recover. But spiritually, the change was stark, and she felt the lack of Arunachala. Then, something amazing happened and the years spent in a cave on Arunachala began to reveal their power:

It had always been my aim to become ‘portable’, not to fall apart because I wasn’t on the Mountain or in Tiruvannamalai, or even in India. That is, to find Arunachala in my heart so that I need not be glued to any physical place, so that the grace I experienced living on the Mountain might be with me wherever I found myself. After all, Sri Bhagavan did say that the real Arunachala is in one’s own Heart. Thus, it turned out that, being pragmatic, I came to be practicing both surrender and enquiry simultaneously, and while this may not suit anybody else, it suited me very well.[21]

Twenty Years Later

A few years ago, Nadhia made a triumphant return to Tiruvannamalai after twenty years away. This time she settled here forever. Her health problems persisted but she took better care of herself. While away, she had continued the work, and it paid off. She once confided:

Having had a rather massive dissociative disorder [in my youth] wherein I would literally evaporate into the left brain and its activities, I knew the work in order to overcome this [was] non- judgmental self-observation, until there was enough space (and a lot of suffering) for the right side to manifest. Once balance was established, enquiry naturally began, [but] it was not gruelling because the purification had eliminated most of the resistance.[22]

In January 2021, friends heard her complain increasingly of various ailments, not just her eyes and back. She suffered pain in the body and her debility and weakness increased right up until late July when in a phone conversation with her sister, Krishna Priya, Nadhia asked her to pray for her which is something she had never done before. Nadhia passed away a week later in her flat at the foot of the Hill.

In the weeks leading up to her departure, she worked with great care on an article for the October 2021 issue of 'The Mountain Path'. She sent it around to friends for proofing and derived a great deal of happiness from working on it.[23]

In putting Nadhia’s story in perspective, it feels like things turned out just as they should have, that Nadhia’s life was somehow complete. While it had been a life full of suffering, it was not a suffering that had been met with self-pity or denial, nor were her hardships something she tried to evade, but rather something she embraced as method and means, like a refiner’s fire, the white-hot smelting that would burn away all that was not gold. Indeed, she bravely enlisted the wounds of her youth as aids in the process, and the closing lines from one of her recent poems[24] suggest that by the time of her demise, this work had come along quite well:

I wake from sleep to sleep again,

the dreamless sleep of sages;

Rising from the dream-life of our infancy,

leaving toys and cradles in the nursery,

Emerging into Stillness and accord,

our separateness dissolving with our cages.

[1] Nadhia was the first of three children born to Louis and Roslyn Teicher. Her father was of Austrian descent and her mother of mixed European ancestry. Her father had been highly influential as music-operations director for the CBS television network for more than 40 years before his death in 1981.

[2] ‘Surrender and Self-Enquiry’, 'The Mountain Path', April 2021, pp.71-77.

[3] Private correspondence.

[3a] Nadhia translated Oleg Mogilever's "INQUIRY INTO THE I - A Garland of Sonnets", which was serialized in the Mountain Path: Aradhana 1990, Jayanti 1990, Aradhana 1991

[4] This story from David Godman.

[5] Personal conversation.

[6] ‘Surrender and Self-Enquiry’, 'The Mountain Path', April 2021, pp.71-77.

[7] Ibid.

[8] ‘Death in Tiruvannamalai’, 'The Mountain Path', April 2020, pp.65-68.

[9] Virasaivism is ‘an offshoot of Saivism and can be traced back to the 12th cent. Its philosophy grew out of the twenty-eight Saiva Agamas and the writings of its early exponents.’

[10]

‘Sravana, Manana and Nididhyāsana’,

'The Mountain Path',

July 2020, pp.101-106.

[11] Notes from Nadhia for ‘In Profile: Therese Rigos’, Saranāgatī, January 2021, pp.3-9

[12] Ibid.

[13] Surrender and Self-Enquiry’, 'The Mountain Path', April 2021, pp.71-77.

[14] Notes from Nadhia

for ‘In Profile: Therese Rigos’,

Saranāgatī,

January 2021, pp.3-9

also see ‘Death in Tiruvannamalai’,

'The Mountain Path',

April 2020, pp.65-68.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17]

‘Śravaṇa, Manana And Nididhyāsana Nididhyāsana’,

The Mountain Path,

July 2020, pp.101-106.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Notes from Nadhia

for ‘In Profile: Therese Rigos’,

Saranāgatī,

January 2021, pp.3-9

[20] Dev Gogoi.

[21] ‘Surrender and Self-Enquiry’, 'The Mountain Path', April 2021, pp.71-77.

[22] Personal correspondence.

[23] "It's Not About the Rain", October 2021

[24] ‘I Wake from Sleep’, published in 'The Mountain Path', January 2021, p.82.

Mountain Path contributions

October 2021 "It's Not About the Rain", pp.31-36Jayanti 1990, "Guhai Namasivaya", pg.115-123