The Recollections of N.Balarama Reddy

Introduction

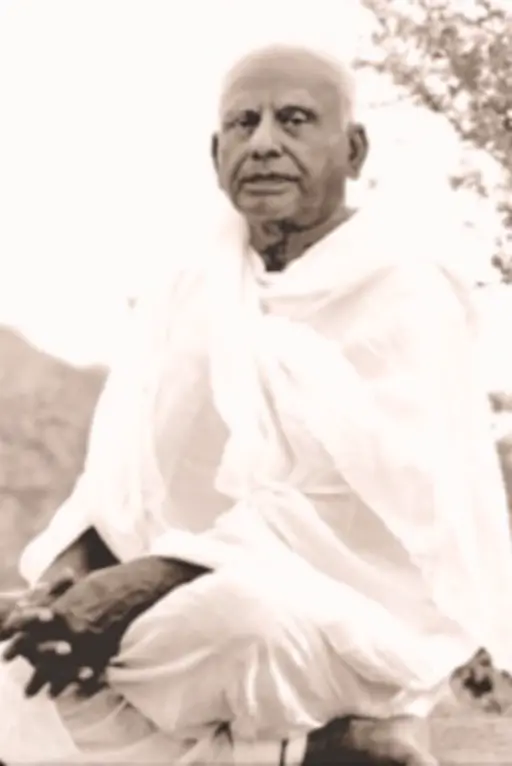

SOON after Sri Ramana Maharshi's Mahasamadhi in 1950, a committee was formed to collect written reminiscences from the Master's devotees. Committee members approached those devotees who were intimate with Bhagavan, had a first-hand experience of his ways and understood his teachings. Arthur Osborne and S.S.Cohen, who were members of the committee, met with N.Balarama Reddy and wasted no time in requesting him to write his reminiscences. Balarama Reddy declined. He told them he mostly sat silently meditating in Bhagavan's presence and never took notes of what he heard or saw.

This does not mean that Balarama Reddy had nothing to relate. On the contrary, he had plenty to tell, and over the years he did convey bits and pieces of it to devotees who sincerely questioned him. But, because of his humble and reticent nature, he never agreed to put his stories down in writing to be published; and it must be added, that during the last forty-five years since the Maharshi's passing, Balarama Reddy was often requested to do so.

During a visit to Sri Ramanasramam in 1993, my name was added to the list of devotees who entreated him to write. After all, he was then in his eighty-fifth year, and how much longer could he delay? I reasoned with him, explaining that where would be the Christ of the Christians if not for Matthew, Mark, Luke and John? I pleaded and said that it was only through his eyes that we, the second generation of devotees, can see and know about the personality that captivated his heart; the same personality that would undoubtedly captivate the hearts of countless future generations. "After you go, this wealth within you will be lost. You must write now while you are still able," I beseeched him.

Balarama Reddy is a kind man, intelligent and wise. If he didn't exactly agree with my argument, he sympathized with my sincerity, and in his goodness agreed - not to write, but to relate to me whatever stories about his life and experience with the Maharshi he could remember. These stories went on to include meetings with Ananda Mayi Ma, Swami Ramdas and other personalities. He fixed a time, between 6:30 and 7:30 in the evening, to meet with me. So I began meeting with him in his room every day for the purpose of hearing his reminiscences. After we met I would put down a few brief notes on the topics of our conversations, and in the morning, following breakfast, I would sit at the small desk in my room and use these notes to recall all I had heard the previous night.

I found this daily exercise to be an exhilarating experience, as I would be so caught up in the flow of the incidents relating to Bhagavan, that I felt as if they were taking place before my own eyes. Balarama Reddy has the power to draw out from his memory, like a spider drawing out its web, the dynamic personality of the Maharshi's presence. He easily caught me in this web, and I sincerely hope these recorded recollections catch many others.

I bow to Balarama Reddy and thank him a million times for kindly dipping into his storehouse of memories and scooping out glassful after glassful of this nectar for me, and all, to drink.

Nova Scotia, Canada

Third Visit to Sri Ramanasramam [part 2]

About a year later, in April of 1936, I had to leave Aurobindo Ashram and return to my village in Andhra Pradesh for two months. My plan was to travel to Ramanasramam at the end of those two months and stay there for seven weeks.

In June of 1936, I arrived at the Maharshi's ashram for a third visit. I was accommodated in the cottage next to Yogi Ramiah's. This cottage is on the west side of the ashram near Palakothu and was built by one of the Yogi's disciples with my namesake - Balarama Reddy. This same Reddy was also responsible for building Yogi Ramiah's cottage.

One afternoon about 2:30 p.m. I casually strolled out of the north gate of the ashram and onto the hill. Observing the majesty of the Holy Hill and studying the summit, a desire arose in me to climb up and see it. I was new in the ashram and had no idea how difficult this endeavor would be, especially since I decided to climb straight up from where I was.

I mentally drew a straight line over the rugged slope and began my ascent. When I reached about halfway up, I met a group of ladies carrying firewood on their heads. They asked me where I was going. After hearing of my plan they tried their best to dissuade me, saying, "The wind is very strong on the upper slopes and you will be blown off and fall to your death, or at least be seriously injured. No one frequents that area of the hill and so you will not be found or saved. Please go back."

I listened to their warnings, which they offered in all sincerity, but as I was still a young man and felt strong, and as I had already climbed more than halfway up, I was loath to turn back in spite of all the dangers they described. Needless to say, after the ladies left I continued my climb.

It wasn't too long before the slope became very steep and, while it slowed me down, this did not discourage me in any way. I came to one point where I had to pull myself up on a narrow ledge. Sitting on that ledge facing the plains I realized that I was unable to stand without losing my balance. In other words, I could not continue my ascent from where I was. On one side of me there was a dangerously steep precipice of more than one thousand feet. On the other side I saw an insurmountable vertical wall of rock. Then, to my great dismay, I realized that not only was I prevented from standing to ascend, I was so precariously positioned on this ledge that it was impossible for me to retrace my steps downward without tumbling head over heels to my death. And to top off all this distress, my sandals were now causing me to slip from the very ledge I was clinging to for my life. I carefully removed the sandals and let them fall down the slope. Sitting with my knees close to my chest and my feet up against my buttocks, I pondered my ill fate. I soon lost all hope of coming out of this ordeal alive. Closing my eyes I began to think of Sri Bhagavan and the Mother of Aurobindo Ashram.

For about ten minutes I sat in this sad condition. While my eyes were closed my head involuntarily turned to my left side. I opened my eyes and saw a clump of vegetation firmly rooted between some rocks. I looked at it and thought that perhaps I could grab onto that vegetation and pull myself up to a standing position. I caught hold of the growth and, to my surprise, executed the feat without much difficulty. And when I did stand up I was utterly amazed when I looked over this ledge and saw that I had reached the summit. Slowly I pulled myself up onto the summit and immediately exhaled a thankful sigh of relief. I walked over to the peak, looked around and soon began my descent down on what appeared to be a frequently used path. Without difficulty I reached the main road and followed it back to the ashram, arriving there just as the evening meal was being served. Without saying anything to anybody about my exploits I sat down with the others and ate.

This event, which was known to me alone, served to deepen my faith in the intervention of the Divine hand. I saw it as an unforgettable milestone in my life of faith and devotion.

During this visit I carefully observed how the ashram was managed and how guests were accommodated and served, and seriously thought about what it would be like to live in the ashram permanently. The presence of the Maharshi, with all his majestic dignity and grace, was a force I could no longer resist. The thought that I might later regret such a move carried little weight when I contemplated the accessibility and spiritual power of the Maharshi. I thought to myself that even if it turns out to be a great mistake, I must not miss this opportunity. I became convinced that my place was there with the Maharshi. I then decided to return to Aurobindo Ashram, wrap up my affairs, obtain the blessings of Mother and Aurobindo, and return to Ramanasramam as soon as possible.

Leaving Aurobindo Ashram

I had been with the Mother and Aurobindo for five years. During those years they showered me with kindness and love, while guiding me on the spiritual path. My gratitude and regard for them compelled me to obtain their permission and blessings before leaving. This turned out to be much more difficult than I imagined.

In Aurobindo Ashram, it was the practice of the disciples who had doubts or questions to write them in the form of a letter to Sri Aurobindo. All the letters were daily collected and taken to Aurobindo, who would sit with the Mother during the nights and promptly answer them in writing. Sometimes we would see the lights burning all night as they were engaged in this work.

Upon my return from Ramanasramam I wrote a letter stating my desire to receive their blessings and permission to live at Ramanasramam. In the letter to Aurobindo I wrote that since your yoga begins with Self-realization, kindly permit me to go to Ramana Maharshi who emphasizes only Self-realization, a state I have not attained, or may not even be worthy of attaining. Aurobindo's reply was affectionate, but negative in regards to my leaving his ashram. He wrote, "Both Self-realization and the supra-mental state can be simultaneously developed and achieved here. There is no need for you to go there."

I was extremely disappointed at his response and consequently became frustrated, restless and discouraged. I soon began to have sleepless nights and felt distraught. I then wrote a second letter to Aurobindo with the same request. Again I was denied permission. It took a long five months and a third letter before Aurobindo and the Mother finally agreed, giving me their permission and blessings. Perhaps they realized I was determined to go and they saw no other recourse but to grant my request.

In Aurobindo's final letter to me he wrote, "Since you are determined to follow a path in which you can achieve only partial realization, we give you our blessings, though we believe it would be better if you stayed on here and pursued your sadhana where both the Mother and I can help you."

It was the rule in Aurobindo Ashram that any letter written to or received from Aurobindo should not leave the ashram premises. So, to comply with this rule, I burnt all my letters, except the final letter I received from Aurobindo. This I kept with the view of showing it to Bhagavan.

Settling at Sri Ramanasramam

On January 5, 1937 I finally arrived at Sri Ramanasramam for good. This happened to be the day after the Maharshi's fifty-seventh birthday was celebrated. As there was still a crowd gathered there for the festivities, I was accommodated with many others in the common guest room for men. Soon after, when nearly all the guests dispersed, I was given Yogi Ramiah's cottage to use. I then thought that I would use this cottage while the Yogi was absent from the ashram, which was most of the time, and find other accommodations during his visits. This seemed to me to be a convenient arrangement. After all, I had now come to settle down there permanently with the Maharshi as my guru. But after only one month had passed, the ashram management informed me that though they didn't want me to leave Bhagavan's holy presence, it was not the practice of the ashram to accommodate devotees permanently. They respectfully requested me to find a place outside and gave me a fifteen day extension to arrange it.

During the early years there were no houses anywhere near the ashram, as it was mostly jungle or forest. I eventually found an upstairs room in a brahmin's house near the Arunachala Temple in town. For my meals I would sometimes cook small items in my room, sometimes obtain food from somewhere outside, and somehow manage without feeling inconvenienced.

Daily I would rise at about 3 or 4 a.m., walk to the ashram, stay in the hall with Bhagavan until 10 a.m., return to my room, come back again to the ashram at 3 p.m. and stay there until 8 p.m. It went on like this during the first year. If possible, I would always sit close to Bhagavan so I could hear all of his precious utterances.

Soon after settling in Tiruvannamalai and surrendering to Bhagavan as my guru I wrote in English, on legal-size paper, a rather long, detailed history of my life and handed it over to Bhagavan. In that letter of several pages I poured out my heart to Bhagavan, withholding nothing. He carefully read through all the pages and then returned them to me.

For the first few months after my arrival Bhagavan would frequently start up conversations with me. With no apparent reason he would start explaining to me a verse, some aspects of a certain philosophy, or a certain spiritual practice. This went on to such an extent that S. S. Cohen, in a light way, complained to me, saying, "Why do you always make Bhagavan talk? I think I am getting jealous."

I naturally protested, "I am not making him talk. For some reason or other he simply looks at me and starts talking."

Often during these discussions Aurobindo's philosophy would come up. And on some occasions Cohen and Chadwick would also join in and try to dismiss any validity to Aurobindo's path. To my surprise, I would find myself defending his philosophy and easily crushing their arguments*. With them I had an easy time, but with Bhagavan it was a different matter. Whatever he would say on the matter was nearly impossible to dispute.

*S. S. Cohen, after repeatedly hearing about Sri Aurobindo, decided that the Yogi from Pondicherry must have some greatness. Consequently, one day he travelled to Pondicherry and while there wrote a note to Aurobindo describing who he was, what he wanted from life (Self-realization) and where he was then residing (Sri Ramanasramam). Cohen later showed me the reply he got from Aurobindo. It said, in brief, that all his aspirations could be fulfilled at Sri Ramanasramam, where he was then living.

I remember during my second visit to Ramanasramam the Maharshi was one day reading a lengthy book review from a newspaper. The book being reviewed was Aurobindo's Lights on Yoga. The reviewer was Kapali Śāstṛi and the editor of this newspaper was Bhagavan's devotee, S.M.Kamath. Bhagavan seemed to take great interest in the review and would occasionally stop reading and comment on what he had just read to those sitting around him. When he had concluded reading it, someone who was aware that I had that very book with me, said to Bhagavan, "This man has come from the Aurobindo Ashram and he has that book with him." Bhagavan turned to me and said, "Oh, is that so? Let me have a look at it."

I went back to my room, fetched the book and handed it over to Bhagavan. Immediately Bhagavan began reading it intently. He kept on reading it well into the night, with the help of a small oil lamp, until he finished it.

When I came into the hall the next day he began discussing the book with me, telling me that a certain term used in the book might look like something new, but it is actually the equivalent of this other term used in such and such ancient text, etc. Like this, he went on discussing and comparing Aurobindo's philosophy for some time. So Bhagavan thoroughly understood Aurobindo's philosophy both intellectually and also from the standpoint of experience.

One evening I said to Bhagavan that the major attraction of Aurobindo's teachings is that it professes that immortality of the body can be achieved. Bhagavan made no comment.

The next day, as soon as I walked into the hall and sat down, Bhagavan looked at me and began saying, "In Kumbhakonam there was one yogi, C.V.V.Rao, who was proclaiming to all, his doctrine of the immortality of the body. He was even so bold as to declare that Dr.Annie Besant (a distinguished public and spiritual personality in India) would have to come to him to learn how to make her body immortal. But, before he had a chance to meet Dr.Annie Besant, he died." This brief story clearly illustrated his point.

On another day, not too long after settling near Sri Ramanasramam, I approached Bhagavan when no one was in the hall and showed him that last letter I had received from Aurobindo. Bhagavan asked me to give it to him to read. I told him he would be unable to decipher Aurobindo's handwriting, as it was very illegible and only those who have studied it for sometime could read it. He said, "Give it to me. Let me try."

After looking into it and realizing he could only make out a few words, he returned it and asked me to read it out. I began reading it and when I came to the sentence, "Since you are determined to follow a path in which you can achieve only partial realization....", Bhagavan stopped me and said, "Partial realization? If it is partial, it is not realization, and if it is realization, it is not partial."

This was the final blow that silenced all my doubts. I then destroyed this letter, like all the rest. And because of all the discussions I had had with Bhagavan I soon felt perfectly established in his teachings, having a clear understanding of where the Maharshi's path and Aurobindo's path diverged and went different ways. When all the clouds of doubts and distractions dispersed, so did our discussions. Bhagavan then knew that I understood and the foundation work had been done. The purpose of all our discussions were served and so they stopped automatically.

Part 3

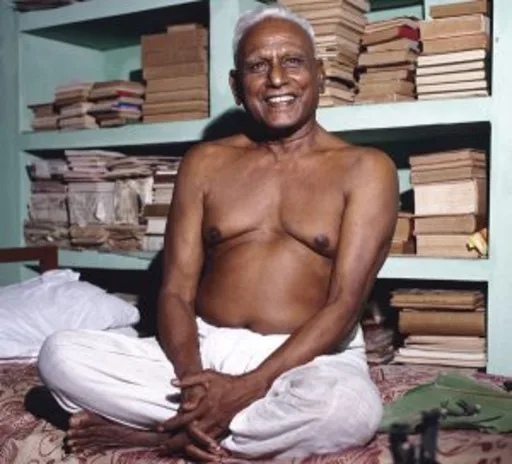

Entering upon the third installment of Sri N.Balarama Reddy's recollections, we are sad to announce the news of his sudden passing on May 11 in Bangalore. Sri V. S. Ramanan, the President of Sri Ramanasramam, informed us that for two months prior to his death Sri Reddy was saying that he did not feel well and had already lived long enough, being in his eighty-eighth year. Sri Reddy's relatives came to the Ramanasramam and took him to Bangalore on April 24. There he underwent many medical tests, and on May 10 a doctor reviewed all the results and said that Mr.Reddy was quite fit and could easily live for four more years. On May 11, the very next day, Balarama Reddy was absorbed into his Master, Sri Ramana Maharshi.(see Balarama's Last Hour)

When I had observed Bhagavan closely for some time I discovered that he would never openly say that he was our guru and we were his disciples; in fact, he would sometimes say things that sounded contrary to this. But for us close devotees there was never a doubt that he was our guru. He loved us like a mother, protected us like a father, guided us like a teacher and moved with us like a friend. We constantly felt his guidance and grace.

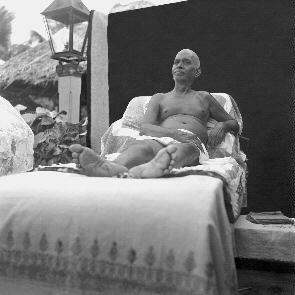

Where do we read in the annals of the spiritual history of India about a sage like Bhagavan, living in one place for fifty-four years, making himself available at all times and embodying such divine qualities? We would sit in the hall and meditate with our eyes closed, or just rest our vision on his form, which we believed to be the form of God. He would teach us orally, or in silence, or again by deed; sometimes in subtle ways, and at other times directly.

When I initially came to Tiruvannamalai and was living in town I would come to the ashram very early in the morning. When the attendant first opened the doors of the hall I would be waiting there. His opening of the door meant that Bhagavan had risen and was about to come out. Before Bhagavan had a chance to come out I would walk into the hall and find him on the sofa preparing to leave. He would often cover himself with a shawl at night and when I would see him removing his shawl I would take it from him and fold it. He was kind enough to allow me this little service.

In those days I was coming to the hall and sitting before Bhagavan in both the mornings and afternoons. During the late afternoons larger crowds were coming into the hall for darshan and causing some disturbance. I then discovered that I could meditate in my room with less distraction in the afternoons and, consequently, began omitting my afternoon visits to the ashram.

One afternoon G. V. Subbaramayya arrived at the ashram and not seeing me in the hall inquired from Bhagavan where I was. The next morning when I was folding Bhagavan's shawl he mentioned about what G. V. Subbaramayya had asked him on the previous day. By this comment I could understand that Bhagavan wanted me to resume coming to the hall in the afternoons, though he did not say so explicitly. In spite of this, I still remained in my room that afternoon.

The next morning when I entered the hall and went over to Bhagavan to take his shawl and fold it he didn't give it to me. He quietly folded it himself. I then realized Bhagavan was admonishing me in this way. After this I saw my error and resumed the afternoon visits to the ashram. From this I realized that Bhagavan wanted us to benefit from his company. But how could he say it openly?

In the first year of my settling in Tiruvannamalai, I remember one afternoon I was sitting in the hall and Bhagavan was explaining to me some particular point on a spiritual matter. During the discussion he asked me to go to one of the two almirahs that were up against the west wall, open it and bring him a certain book. I searched for the book but was unable to find it. I returned to Bhagavan and informed him of my failure to locate the book and then again sat down against the south wall facing him.

Presently, I saw Bhagavan alight from his couch, slowly and majestically walk over to the almirah, open it, and immediately pull out the book he asked me to find. He closed the almirah and, to my surprise, instead of walking back to the couch, he came and sat on the floor right next to me, on my left. He opened the book to the page he wanted me to read and, holding it in his right hand, held the opened book before my face and asked me to read the particular passage.

Attendants of Bhagavan had earlier told me that Bhagavan's body was like a furnace. Only then, when he sat so close to me, could I understand what they meant. I felt like there was an electric dynamo of spiritual power emanating from his body. I was thrilled to the core of my being.

I believe the most unique characteristic of Bhagavan was the power of his presence. Much of what he taught had already been transmitted to the masses down through the ages. In Bhagavan we found a being that was surcharged with the Reality to such an extent that coming into his presence would effect a dramatic change in us. This Divine Power of his presence was something remarkable, entirely outstanding in this century. But why just this century? It must be so for many centuries.

I always felt there was something tangibly distinct in Bhagavan's hall. When we walked into it and sat down we immediately felt like we had just entered a different sphere of existence. It was like the world we knew did not exist there - Bhagavan's presence, his other-worldliness, would so envelop the atmosphere. When we again walked out of the hall we were confronted with the old world we knew all too well. Nowadays we see many spiritual teachers opening schools, hospitals and the like. All this philanthropy has a purpose, no doubt, but Bhagavan never asked us to do such things. He wanted us to do one thing only, that is to know who we are, to know the Self. He believed this to be the panacea for all human suffering and the goal of life. But how many of us are adequately earnest to seek the Self alone? We are continually diverted and distracted by what we call "helping the world". Where is the world? And who are we? This is what we should be looking into.

In January of 1938, after staying with the Maharshi for one year, I returned to my village. I was planning to go again to the ashram after a couple of months, but before returning I decided to make a trip to North India.

After hearing very favourable remarks about Sri Krishnaprem from Dilip Kumar Roy in Aurobindo Ashram, I had a desire to visit him at his ashram in the Himalayas. He lived about eighteen miles from Almora.

I left my village and travelled by train to Delhi. From there I immediately boarded another train for Barelly, Uttar Pradesh, where I changed to another train that took me north to Kathgodam. I was advised to get down at Haldwani, one stop before Kathgodam, and board a bus for Almora. Following this advice, I arrived at Almora in the evening and spent the night in a dharmashala. About 8:30 a.m. I hired a coolie to carry my luggage and then began the eighteen mile trek through the forest and hills to Sri Krishnaprem's ashram in Mirtola. We covered about two miles every hour and reached the ashram by 4:30 p.m.

Approaching the ashram I could see from a distance his tall figure standing outside. I had not written him prior to this visit, nor did he have any idea who I was or where I was coming from. Nevertheless, he greeted me warmly, asked me to take my things to an adjacent guest room and then return to him for refreshments.

Krishnaprem was living there with his guru, Yashoda Ma. When Swami Vivekananda was still an unknown wandering monk, he chose the young daughter of a gracious host at Ghazipur for symbolic worship in Kumari Puja, as observed in Bengal. That same little Brahmin girl would one day become Yashoda Ma, the guru of Krishnaprem.

Krishnaprem's pre-sannyasa name was Ronald Nixon. He was a brilliant graduate of Cambridge, who came to India drawn by a spiritual thirst unquenched in England. He taught English literature at the universities of Lucknow and Benares before renouncing and becoming a Vaishnava monk. Krishnaprem spoke fluent Hindi and Bengali, and he was also a serious student of Sanskrit and Pali.

Their ashram building had a shrine room, kitchen, library and a couple other rooms on the ground floor. One additional room was built upstairs. The land they bought was three miles in circumference. Krishnaprem told me that the broker who arranged the purchase deceived them on some details. They, however, decided to make the best of it and appeared to be quite settled when I made this visit in May of 1938. To me the ashram was like an isolated oasis, surrounded by trees and hills, and far removed from the scorching summer heat I had just experienced in the plains.

I had brought with me two sapota fruits from my village garden, which I offered to them. They had never seen this variety of fruit and became extremely interested to know all about it. After eating the fruit they saved its black seeds with the intention of planting them in their garden. I saw that they were growing many fruits and vegetables and, I was told, had even tried their hand at starting a tea garden, but because of the excess of humidity in those hills it failed.

When Krishnaprem and Yashoda Ma came to know that I had spent five years in Aurobindo Ashram and one year in Sri Ramanasramam they became keen to hear all about Bhagavan and Aurobindo. I had planned on staying with them for only three days, but when I started telling them stories about Bhagavan and Sri Ramanasramam they decided I should stay a month - so intrigued were they on hearing about the Maharshi. I was not prepared to make a longer stay and so left them as scheduled.

During this short visit I was able to observe that they were living an exemplary life of one-pointed devotion and intense spiritual practice. Apparently, the weather of this mountain retreat favoured Yashoda Ma's health, whereas the weather near the sea favoured her husband's. Thus, for health reasons, they lived separately. Yashoda Ma's daughter was also then living at the ashram, and Yashoda Ma had so much faith and trust in Krishnaprem, she had given her over to his care. He, on his part, looked after her like his own ward.

When Krishnaprem asked Yashoda Ma to initiate him and make him her disciple, she said, "Yes, I will. But there is one condition. That is, that you never complain about your spiritual progress." He consented and till his end was fully satisfied with the stature and grace of his guru.

Many years after this visit I received a letter from him wherein he wrote that we were both blessed: me, because I had Bhagavan as my guru, and he, because he had Yashoda Ma.

I stuck to my plan and left their ashram after the third day, returned to Almora and then travelled to Dehra Dun. From there I boarded a bus for Rajpur, which is just seven miles south of Mussoorie. A one mile walk up the hill from Rajpur was the ashram of Dr.K.D.Śāstṛi. In 1931, after leaving my studies in Benares, I visited this ashram. Even when I had come here seven years earlier, its founder was already deceased and his American wife was managing the institution. It was founded for the purpose of teaching young people spiritual traditions, Indian History and other cultural subjects. When I first went there in 1931, T. L. Vaswani was a resident teacher. He was then a popular author of many respected books, an acclaimed public speaker and an esteemed spiritual personality in his own right. Prior to teaching in this ashram he was the chancellor of a college, a job he resigned for the purpose of becoming a sadhu; a title which later became a prefix to his name - Sadhu Vaswani. He was not teaching in this ashram when I came there this second time.

Soon after arriving at Dr.K.D.Śāstṛi's ashram someone asked me if I had met the Bengali mystic-saint who lived just four miles south of there. I had not, and so was encouraged to again take the return bus and get down at Kishenpur, which was just halfway between this ashram and Dehra Dun.

Alighting there I inquired and soon found the house of the saint. I was met at the entrance and escorted to a room where I was asked to enter and take a seat on the floor. Before me sat a remarkable looking woman, clad in a white sari, sitting on a white sheet that was spread over a thin mattress laid on the floor. Her spiritual charm and the cool breeze of peace and harmony that she radiated had an extraordinary effect on me. I almost felt as if I was sitting before the Maharshi himself. And in many ways similar to the Maharshi, glowing with warmth and illumination, sat a rare spiritual personality of the twentieth century, Ananda Mayi Ma. She was then 42-years old.

In an endearing manner she made kind inquiries about matters concerning my life. As we were talking the room slowly filled up with visitors. I told her that I had just come from Krishnaprem's ashram. After hearing that she said that Krishnaprem and Yashoda Ma had created an Uttar (north) Vrindavan in Almora.

When I looked around the room again I saw many devotees had gathered. Some were meditating, some were talking quietly among themselves and others began questioning Ananda Mayi Ma on certain matters. Everything seemed to be going on spontaneously in a natural manner. There appeared to be no enforced code of behaviour in Ananda Mayi Ma's presence, which immediately reminded me of the Old Hall at Sri Ramanasramam.

At about noon the saint stood up and walked out of the room. A few of the devotees followed her and I decided to do likewise. She walked to a doorway of another room and stood there looking in. I also looked into that room and saw a bearded, middle-aged man lying on the floor writhing in pain. I was surprised to have recognised this man from an incident that occurred two days earlier, while I was travelling to Rajpur:

When I was in Dehra Dun and boarded the bus for Rajpur, this same bearded man had entered the bus and sat next to me. The bus was nearly full and, although it was the scheduled departure time, the bus driver and ticket collector had not yet made their appearance. Consequently, most of the passengers began to show signs of impatience, especially this bearded gentleman seated beside me. He went to the point of getting off the bus and shouting out loud for the driver, imagining that he was in some building nearby neglecting his duties. I later discovered that this might have been true. Probably for financial reasons, dictated by the bus owner, the bus personnel were notorious for not showing up till the bus was filled to capacity, regardless of the scheduled departure time. Eventually the driver appeared, the passengers grumbled a bit and we left Dehra Dun.

Standing in the doorway, seeing this same bearded man terribly ill, I was told that he was the husband of Ananda Mayi Ma. How Ananda Mayi Ma happened to marry him, the relationship they had together and how they came to move from Dacca to this place makes quite an interesting story.

I was later informed that on the day of my first visit to Ananda Mayi Ma, her husband was ill with smallpox. Knowing this, Ananda Mayi Ma asked her mother and a resident disciple known as Didi to leave the house and live elsewhere. Of course, they objected. She then told them if they did not leave, she would. Ultimately, they were persuaded to leave and Ananda Mayi Ma was left alone to attend to the needs of her sick husband.

Her husband was a good man, loved by all of Ma's followers. He was even looked upon as a father figure in the ashram and, although he was well served by his wife during this illness, he eventually succumbed to the disease. Perhaps she had anticipated this and wanted to be alone with him during his last days. Just before dying he joined his palms together in salutation and said to his wife, "You are my Mother." There is little doubt that Ananda Mayi Ma did more than attend to just his physical needs during those last days. The time she spent alone with him certainly must have brought him far along on his spiritual journey.

In the afternoon I returned to Dr.K.D.Śāstṛi's ashram. A younger American sister of K.D.Śāstṛi's widow was also in the ashram at this time. She was interested in studying music and was taking lessons in Lucknow. She was also quite interested in coming to Tiruvannamalai to meet Bhagavan. Before leaving there I told her to write to me and come to Ramanasramam when I was present in the ashram. She somehow came when I wasn't present, stayed in the Morvi Guest House and was relieved of over four hundred rupees by a thief. She had no idea of what security precautions to take. In due time she left India and returned to America.

After a two or three day visit to the Rajpur ashram I left for Vrindavan. I had no special desire to visit Vrindavan at that time, but Krishnaprem made me promise that I would stop there while returning south. Yoshada Ma's guru, a sannyasi, lived there and they wanted me to meet him. Also, they wanted me to visit a few of Krishnaprem's disciples who lived in a house they owned in Vrindavan. When I arrived I immediately went and visited the sannyasi and disciples and was able to board a departing train the very same day. Although I was then feeling eager to return to Ramanasramam, I decided I would break my journey once more before reaching Tiruvannamalai.

Part IV

About a year earlier I had left Tiruvannamalai for a month and visited Swami Ramdas at his Ananda Ashram in Kanhangad, Kerala. The Swami's brother-in-law was an officer in the revenue department and the land allocated by the government for Swami Ramdas to set up his ashram was acquired through his intervention. In fact, his brother-in-law's property bordered the ashram.

After Ramdas left his home and became a mendicant sadhu, his wife and daughter came to live here with his wife's brother (the same brother-in-law). Even at the time of my first visit to Ramdas in 1937, his wife had already passed away, but other relatives, including his daughter, would visit the ashram daily.

Amongst all these family members and devotees the Swami would cheerfully move about, never putting on the airs of a sannyasi or even that of a householder. He treated everyone as if they were all part of the same family, in a very natural, affectionate and, above all, detached manner. It was a delight to watch him. In all guilelessness and humility he would sit down with anyone and begin narrating one story after another, all from his personal life and experience. On my first visit in 1937 there was only Mother Krishnabai and two or three sadhus living in the ashram. Ramdas would be engrossed in telling me some story or reading from his manuscripts when Mother Krishnabai would appear with cooked food and feed us. In the course of one of these stories Ramdas told me how he came to Arunachala and saw Bhagavan. When he was a mendicant and was travelling to all the holy places, he heard of Arunachala. He had also heard of Ramana Maharshi, but to see him was not the main purpose of his visit to Tiruvannamalai.

Soon after reaching there he came to Ramanasramam and stood before the Maharshi, who was then sitting on a raised platform. Ramdas said that he felt Bhagavan's grace pouring out through his eyes and filling him. After having Bhagavan's darshan he went up on the hill and resided in a cave and performed continuous round-the-clock japa. He said that by doing this constant japa he lost his mind and after two weeks the universal vision of God appeared to him. In other words, he saw everything as God. Since that day, he said, he has been living in Ram. Ramdas had received the Ram Mantra from his father and he was one of those few great souls who could execute his sadhana to completion without the help of a physical guru.

During my first visit, Ramdas was present for only two of the four weeks I stayed in his ashram. Devotees from Maharastra were eager to see him and so he had travelled there. After he left, Mother Krishnabai was kind enough to tell me some stories from her life, describing how she came to Ramdas and other personal matters. It was all very interesting and elevating. When I returned to Ramanasramam I received a letter from Ananda Ashram wherein they requested me to write in English all I had heard from Mother Krishnabai relating to her personal life and experiences. I did this for them and it was included in a biography they published of her. Also, when I was in Ananda Ashram in 1937, I had written to my family in Andhra to send a certain quantity of rice to this ashram for their use. Later, when I returned to Ramanasramam, a letter arrived from Swami Ramdas in which he wrote they had received the rice and that it was much superior to the scented rice they were presently using. I showed the letter to Bhagavan.

Not long after that, when I was alone with Bhagavan, he asked me about Swami Ramdas. He wanted to know his daily schedule and, in particular, what he did in the mornings. It was unusual for Bhagavan to inquire about others in this manner. I then told him that someone had suggested to Ramdas that he should daily practice a certain pranayama exercise, as it would be good for his health. It simply involved inhaling slowly and deeply, and exhaling slowly, without any breath retention. He was doing this for one hour every morning. I also told Bhagavan other matters concerning his daily routine. When I visited Swami Ramdas on my return from North India in 1938 I only stayed a few days. Upon leaving, Mother Krishnabai gave me some food items to offer to Bhagavan. The practice of sending certain food items to Ramanasramam from Ananda Ashram became an established tradition which continues to this day. For Bhagavan's Jayanti celebration Krishnabai would send a large quantity of dried banana chips and kanji. Even after her passing these generous offerings continue, not only for Jayanti, but at other times as well.

It was near the end of May in 1938 when I returned to Ramanasramam from North India. When my bus was approaching the ashram on the Chengam Road I asked the driver to stop and let me off near Palakothu, just west of the ashram. S.S.Cohen occupied a small cottage there and during my previous stay in Tiruvannamalai he often requested me to come and live with him in Palakothu. I decided to take him up on the offer. Leaving my luggage in his room, I walked over to the ashram, entered the Old Hall, prostrated before the Maharshi and sat down until 11:00 a.m., which was the dinner time. I then returned to Cohen's cottage to eat. I didn't realize at the time that devotees just arriving after a long absence were usually requested to take their first meal with Bhagavan, even though, as in my case, they may be living outside the ashram. When Bhagavan came to Palakothu on his walk after lunch, his attendant stopped and told me that Bhagavan, not seeing me in the dining hall, had inquired as to my whereabouts. The attendant stayed and talked to us as Bhagavan continued on alone. I was very touched by the Maharshi's solicitude. I met him as he was returning from his walk and told him about my North Indian trip. I began narrating my visit to Krishnaprem and told Bhagavan how keen he was to hear all about him and Ramanasramam. It was then the month of May, the hottest time of the year. I explained to Bhagavan how delightfully pleasant and cool the climate of Almora was, especially compared to the present weather in Tiruvannamalai. Bhagavan said, "The real coolness is within. If we have that coolness it will be cool wherever we go. Similarly, if you want to protect your feet from the rough ground, you don't try to cover the earth with a piece of leather. You simply put leather shoes on your own feet and the job is done."

Mouna

One night, not too long after moving in with S.S.Cohen at Palakothu, some time after 9 p.m., I had an urge to go on pradakshina around Arunachala. I was then staying on the verandah of his cottage near the outside door, which enabled me to come and go without disturbing him. He probably didn't know I went out that night.

I was slowly walking around the hill when I came near the Kanji Road. This is just halfway around the hill and near what is now called "Sri Bhagavan's Bridge," named because Bhagavan would often stop there and rest on it. I was looking at the holy mountain, surcharged with peace and silence, when a strong feeling arose from within to take a vow of mouna (silence). On the spot I resolved to stop speaking to anyone, except those occasional exchanges I may have with Bhagavan. In the morning, when Cohen met me he began talking to me in his usual way, he soon discovered I was not responding. I wrote on a piece of paper about my decision to observe mouna, which took him by surprise. It was not long before everyone in the ashram knew.

Swami Viswanathan was at that time translating Swami Ramdas' book, In the Vision of God, into Tamiḷ. He was corresponding regularly with Ananda Ashram, and in the course of this correspondence he had written about my observing mouna. Soon after this, he received a letter from Ramdas wherein the Swami wrote: "Balarama Reddy is observing mouna? That is very good. He is a pure soul."

A day or so after this letter arrived I was entering the ashram one afternoon at about 5 p.m. by way of the stairs on the north side. One has to ascend a few steps and then descend a similar number of steps which takes you down to the ashram level. These steps take you over the bund on the side of a small canal bank where water would flow during the rainy season. When I had reached the top of the stairs I met Bhagavan and his attendant proceeding in the opposite direction. I stood aside to let them pass. Bhagavan looked at me and said, "Viswanathan received a letter from Swami Ramdas and Ramdas wrote: 'Balarama Reddy is observing mouna ? That is very good. He is a pure soul.'" Bhagavan repeated this quotation to me in English.

Bhagavan's mentioning this, provided me with the assurance that my decision to observe mouna was correct. It was sometimes difficult to tell if Bhagavan approved of a certain act or discipline, as he interfered very little in our outward lives. But if we kept alert, he would somehow let us know in one way or another - often in a subtle manner - that what we were doing was correct or incorrect.

Once Major Chadwick decided that he too would observe mouna, but Bhagavan made it clear to him that it wasn't necessary or advantageous in his case.

I continued observing silence from June 1938 to September 1939 when something Bhagavan said induced me to end it. In September of 1939, I was sitting near the end of Bhagavan's couch, where his feet rested. There wasn't a fence around the couch in those days and we could easily sit close to him. It was about 7 p.m. when I opened my eyes from meditation and saw sitting before me T.L.Vaswani and his nephew, J.P.Vaswani. T.L.Vaswani recognised me and I joined my palms and saluted him in greeting. As I was still observing mouna, I didn't say anything to him. The dinner bell rang, everyone got up and left and I returned to my residence. After breakfast the next morning, I told Bhagavan the identity of our guests and inquired about where they had gone. T.L.Vaswani was renowned all over India but, like many famous people back then, very few could recognise him by sight. I was surprised to hear from Bhagavan that he and his nephew had already departed. I was disappointed that I had no chance to communicate with them or inform anyone who they were before they left. When I had expressed all this to Bhagavan he told me that I could have said something to him on the previous evening. Bhagavan's mentioning that I could have said something, gave me an indication that my silence was now not necessary in his view and I should end it, which I did. I later wrote to T.L.Vaswani and expressed my disappointment at his early departure from the ashram, and explained how I had been then observing mouna. I also related to him my conversation with Bhagavan after his departure and how it resulted in my abandoning a vow of silence. He wrote back praising Bhagavan, expressing how blessed I was to be sitting at the feet of a sage like the Maharshi.

In this same year, 1939, I occupied another hut near Cohen's in Palakothu. This hut consisted of two small rooms, about six feet by eight feet each. I stayed in one of these and Swami Prajnanananda, a westerner, was using the other. One night before I returned from the ashram, someone broke the lock on the door and made off with my suitcase and some other things. The next day I searched in the nearby woods and found the suitcase, which contained mostly books. The books were scattered around near the suitcase. I collected them and returned to my room. A short time later there was another robbery. Someone pounded a hole in the mud wall near the window frame. At this exact place I kept some money in a jar. Somebody must have seen me taking money from there and got the idea of stealing it. The next day when Bhagavan came to Palakothu on his walk I told him about the theft. He looked over the scene and explained to others how some of these local people keep an eye open for such opportunities, and how they must have seen me take money from that jar and decided to pound a hole in the wall to get at it. He then told me that I should not keep anything in this place that would be desired by others. I therefore shifted my belongings to town and gradually moved back there myself.

My Father's Death

Not long after I ceased my mouna I received a letter from my mother asking me to come home for a visit, since she had not seen me for a long time and was missing me. I returned home and just four days after my return, on November 10, 1939, my father unexpectedly collapsed with a heart attack and died. It was about 9 p.m. on the night of Deepavali when someone came running to my garden cottage and told me to come immediately to the main house. By the time I arrived at the house it was all over: my father had expired. It seems he took his evening meal as usual and was relaxing when he experienced a sharp pain in his chest. As he lay there suffering he told my brother and mother that he felt his prana (life force) leaving his body. He first described to them how it was leaving his lower extremities and was slowly working its way upwards. When it had reached his chest he said he would now die and gave instructions as to where his body should be buried. All this happened within half an hour.

I wrote to the ashram and informed them of my father's demise. Viswanathan later told me that Bhagavan read the letter and commented to those around him "that it was all over in half an hour." Two years earlier my father had come to Sri Ramanasramam and had Bhagavan's darshan. The fact that I was able to return home just a few days before my father's end - and many other such incidents in my life - instilled in me faith in the guiding presence of the Maharshi. I also felt assured that surrendering to him as my guru and master was the best decision I had ever made.

Soon after my father's demise I left my village and returned to the ashram to attend Bhagavan's sixtieth birthday celebration, which fell on December 27, 1939. In our Indian tradition the sixtieth birthday is considered an important event in one's life. It is called Shashti Purthi, and many devotees attended the occasion.

Bhagavan's Love and Care [part 5]

It is hard to describe, and it was a wonder to see, how Bhagavan bound all with his love. Between Bhagavan and some of his long-standing devotees words would never pass. Nevertheless, these devotees, whether men, women or children, knew that Bhagavan's love and grace was being showered on them. By a single glance, a nod of the head, or perhaps by a simple inquiry from Bhagavan - sometimes not even directly but through a second person - the devotees knew that he was their very own and he cared for them. In his presence all distinctions and differences were resolved. We lived together like a huge family with Bhagavan at the center, guiding us and shedding his grace and blessings on all.

Bhagavan was most considerate and kind-hearted, but at the same time he was a strict disciplinarian. Even if he appeared indifferent to the onlookers, he still took a keen interest in the progress of seekers, particularly if they happened to be youngsters. Many times I was helped by Bhagavan.

Later, for instance, due to a crisis in my home, I was informed that my continuous presence in the village was now required. That meant I would have to leave Bhagavan for good. When I received this news I went and explained it all to Bhagavan, who kindly listened and then simply nodded his head. The meaning of this nod I understood only upon receiving a letter from my mother, who wrote that I need not leave the presence of Bhagavan and that she would attend to all the affairs in the village. This was a turning point in my worldly life and it was due, no doubt, to the direct intervention of Sri Bhagavan's Grace. When I showed my mother's letter to Bhagavan, he read it and gave me a benign smile, as if to say: "Are you now satisfied?"

It was a mystery to see how he was so detached from the ashram and its operation, but yet was still somehow getting everything done as he wished. The Sarvadhikari, Sri Niranjanananda Swami, once told me, "It is difficult for others to understand, but sometimes I feel there is something like a wireless connection between me and Bhagavan."

Niranjananda Swami

Bhagavan's brother had to endure considerable criticism while managing the ashram. Even so, there is little doubt that Bhagavan used him as his instrument. When Niranjanananda Swami felt an inner prompting from Bhagavan, he confidently acted on it. The following may be an example of one such occasion.

It is widely known that Paul Brunton's book, A Search in Secret India, did much to make known to the world that the Maharshi, a unique sage of this century, was living inTiruvannamalai. Brunton was a professional writer and in those days wherever he would go he would often be seen taking notes on bits of paper. While in the Old Hall listening to questions put to Bhagavan and his replies, he would be eagerly taking notes. After the success of A Search in Secret India, he began writing many other books in which he would sometimes adopt the Maharshi's teachings without giving due acknowledgment. When the ashram authorities realized this they decided to stop him from taking notes in the hall.

One day in 1939, Brunton was sitting next to me taking notes as usual when Niranjanananda Swami boldly walked into the hall, stood next to Bhagavan and told Munagala Venkataramiah to tell Brunton in English that he is no longer permitted to take notes while sitting before Bhagavan. Brunton was told accordingly. Brunton looked at Venkataramiah and said, 'Is this also Bhagavan's view ?' Venkataramiah did not reply to this question and Bhagavan who was quietly sitting there didn't say a word either. A few tense moments passed. Then Brunton stood up and left the hall. That was the last time he took notes in the hall, and that was also when Brunton began distancing himself from the ashram.

It was very unusual to see the Sarvadhikari appear so bold and authoritative before the Maharshi. He must have felt that this exploitation should stop and was confident that Bhagavan was behind him.

Correcting Proofs and Settling in the Ashram

It was perhaps a year or two later, when I was preparing to make a trip back to my village, when Bhagavan asked me to check through the proofs of the fourth edition of Self Realization, written by B.V.Narasimha Swami. I was in the hall and getting ready to take leave of Bhagavan when the final proofs - we called them "strike forms" back then - for the fourth edition of Self Realization were handed over to Bhagavan. He called me, handed over the proofs and requested me to go through them. I thought it odd that although Bhagavan knew I was planning to leave that day, he would detain me with some work. It is said in the scriptures that the guru blesses his sishyas (disciples) by giving them work to do, and so I naturally felt blessed at his request, especially because he would rarely ask any one of us to do anything for him.

When I had gone through one proof, another would arrive, and in this way my trip home kept getting delayed. When I had finally finished all the strike forms and showed Bhagavan the errors, he expressed surprise and said, "I have gone through these proofs, others have gone through them, and after all of this Balarama Reddy finds more errors!" The corrections I found had to be added in the end of the book under the title 'ERRATA.'

Completing this work, I returned to my village for the summer months. While I was there the newly-printed fourth edition of Self Realization arrived at my house by post. The book was inscribed: 'With the blessings of Sri Bhagavan.'

Perhaps Bhagavan had reminded the office that I had worked on the proofs and requested them to send me the new release. I have preserved that book in my village.

When I returned at the end of the summer, the ashram administration, for some reason, made a change in their policy regarding my residence in the ashram. It was my regular practice to stay a few days in the ashram and then settle into some rented room in town. This time the management favored me by letting me remain in the ashram itself. I placed my things in the northeast corner of the Guest House for Gentlemen. The ashram kindly gave me a very large, thick Malaysian mat, woven with split bamboo, to spread on the floor. I hung carpets on the west and south sides and thus created my own simple room, which I found quite comfortable. I believe I may have been at that time the only devotee allowed to live in the ashram and not required to do some form of service or make payments.

All this happened in a natural, spontaneous manner. It was as if the ashram had accepted me as a family member, and when we visit our home where do we stay - not in some rented room?. How fortunate I felt. It was all Bhagavan's grace.

Sanskrit

In my youth, when I was attending a Christian school, I began to study Sanskrit. However, the school decided to drop this subject from their curriculum soon after my studies began. Later in life, when I left the university and directed all my attention toward the spiritual ideal, I resumed studying Sanskrit on my own. But for some reason or other, these studies didn't proceed well either and I soon dropped them. Then, when I settled down at Aurobindo Ashram, I again thought I should take up the study of Sanskrit. The main focus in language at Aurobindo Ashram was to improve our proficiency in English, not Sanskrit; and although I did improve my English considerably at Pondicherry, Sanskrit studies remained an unfulfilled aspiration.

One evening, after I had settled in Bhagavan's ashram, I saw two large volumes and an oil lamp on the stool next to Bhagavan's couch. I asked Bhagavan what those books were. He told me that they were two volumes of Yoga Vashistam, a famous Sanskrit text, and then went on to extol the wisdom of the verses in the books. Regretting my inability to learn Sanskrit, I told Bhagavan that although I had attempted to learn the language three times, to that day I had learned very little. He kindly replied, "I don't know much either. I don't even know rama sabda - the first rule of Sanskrit grammar." This encouraged me to learn more Sanskrit in Bhagavan's presence, especially as I noticed how Bhagavan took great interest in Sanskrit compositions and was all praise for Ganapati Muni's mastery over the language.

One time a Sanskrit professor from Annamalai University was in the hall speaking to Bhagavan in Sanskrit. Bhagavan could understand spoken Sanskrit, but didn't speak it himself. He was closely following what the professor was saying and I, sitting nearby, was also able to grasp most of what was being said. When this had gone on for some time, all of a sudden, I lost the thread of the conversation. At that very moment Bhagavan turned to me and asked, "Did you follow that?" I was amazed how he caught me at the very moment I got lost.

Once Bhagavan mentioned about a Sanskrit biography of Saint Manikkavachakar. The particular book he was speaking about was a transliteration of the Sanskrit text into Telugu. Some of us devotees took it upon ourselves to locate this book and bring it to Bhagavan. We searched long and hard, as it was out of print for many years. Finally we were able to secure a copy from the estate of an influential zamindar (landholder). When we presented it to Bhagavan he seemed pleased and then asked me to begin reading aloud in the hall. I began and, as the time passed, Bhagavan's head leaned back on the pillow and his eyes shut. An old devotee of Bhagavan, one Subba Rao sitting by my side, signalled me to stop reading, as it looked obvious that Bhagavan had dozed off. I didn't stop immediately, but after his repeated silent requests, I stopped. The instant I stopped Bhagavan opened his eyes, looked at me and asked why I stopped. Usually we could not tell if Bhagavan was asleep or awake, though, in reality, he was always awake, awake to the Self.

Sometimes we would approach his couch, see him reclining with his eyes shut and softly say, "Bhagavan." I suppose we thought if we spoke softly and he didn't hear us, it meant that he was sleeping and, if he did hear us, he would respond without us disturbing him, as he was obviously awake and just resting his eyes. But however we reasoned, whenever we approached him in this manner, he would immediately open his eyes and say, "Yes, what is it?"

The Sanskrit recitation of the Vedas morning and evening in Bhagavan's presence was usually well attended. Initially, some priests from the main temple in town began coming and reciting before Bhagavan, thinking, perhaps, it was edifying for them to do this in the august presence of the Maharshi. Although everyone liked this, it was not performed with any consistency, depending mostly on the whims of the priests. The Sarvadhikari thought the ashram should have similar daily parayanas in a routine way. With this end in mind, a Veda Patasala, or Vedic school, was established in the ashram. The students, much like today, would come twice a day and recite before the Maharshi. Now the only difference is that they recite before Bhagavan's tomb. Bhagavan often commented on the value of listening to the Vedic chants. We would normally see him sitting fully alert and absorbed throughout the duration of these recitations.

In 1942, Bhagavan was near the back steps of the ashram when he abruptly placed his stick before the path of a dog that was in hot pursuit of a squirrel. In this successful attempt to save the squirrel, he lost his balance and fell, fracturing his right shoulder. Soon after this incident, when I was taking leave of Bhagavan to visit my village, I looked at the bandaged shoulder and wanted to ask him how he was feeling. But how could I? I knew perfectly well what his reaction would be to such a question regarding his physical well-being.

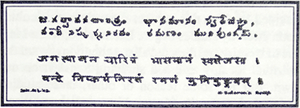

Reaching my village, I wrote a letter to Bhagavan in which I quoted the following verse:

'It is improper to make inquiries about the health and welfare of those whose sole delight is in the Self, since they are strangers to those mental states which distinguish between weal and woe.'

In addition to this, I also included a short Sanskrit verse that I composed.

When I returned to the ashram, one of Bhagavan's attendants told me that on the day my letter arrived, Bhagavan removed it from the other letters and put it by his side. He later returned all the letters except mine. Subsequently, he asked the attendant to bring him the big notebook in which all the verses composed on Bhagavan were recorded. Then, in his own hand, he copied the Sanskrit verse I composed into the notebook. He not only copied the Telugu script, which I had written it in, but also transliterated it into the Devanagari script. Then, with a red ink pen, he artistically framed the verses using two close parallel lines, one thicker than the other. The finished product looked like a piece of art. When I heard all this from the attendant and saw what Bhagavan had written in the book, I was very moved by the solicitude and attention he extended to me.

Many years later I asked President T.N.Venkataraman if I could cut out from that big book my verse written by Bhagavan. He gave me permission and I now keep it in my album containing photos of Bhagavan. Below is a copy of what Bhagavan wrote in the notebook, followed by my English translation.

'I salute Ramana, who shines by the effulgence of the Self, who delights in non-action, and whose life purifies the world.'

In January of 1946, Bhagavan came across a verse in the Srimad Bhagavatam that seemed to have appealed to him immensely. He first found it in the Tamiḷ Bhagavatam and then searched and found it in the original Sanskrit Srimad Bhagavatam. He then made his own Tamiḷ rendering of it and, at my request, translated it into Telugu, my mother tongue. Because Bhagavan was giving this verse so much time and attention I naturally thought it must convey a special meaning, especially in regard to his own spiritual experience. The literal translation in English is:

'The body is impermanent (not real). Whether it is at rest or moves about, and whether by reason of prarabdha it clings to him or falls off from him, the Self-realized siddha is not aware of it, even as the drunken man blinded by intoxication is unaware whether his cloth is on his body or not.'

Bhagavan showed me his Telugu translation and asked me to correct it. When I protested, saying, "How can I correct Bhagavan's writing?" he simply said that he must take advice from those who are proficient in whatever language he happens to use.

Ganapati Muni [part 6]

After Ganapati Muni died, Bhagavan would always turn down requests to compose anything in Sanskrit. He never studied Sanskrit grammar and composed verses only through inspiration. He would say now that Nayana (Ganapati Muni) is gone, who could he turn to for assistance? He had complete faith in Nayana's knowledge of the language.

I never met Ganapati Muni, but I remember being with Kapali Śāstṛi in Aurobindo Ashram when the news of his death arrived. I saw Śāstṛi openly weep, lamenting the Muni's death. At that time Kapali Śāstṛi had so much faith in Aurobindo and Mother, I heard him say, "If Nayana was here (at Aurobindo Ashram) he would not have died."

Nayana died in 1936 at Karagpur in West Bengal. A telegram relating this news was sent to Sri Ramanasramam, and then from there another telegram was sent to Aurobindo Ashram. Swami Viswanathan told me that when Bhagavan read the telegram, these few sad words fell from his lips: "Where will we find another like him?" Ganapati Muni was no ordinary sadhaka. He believed he was born on earth for a mission. He had great power and intelligence, and desired to rejuvenate India through mantra japa.

Bhagavan was once talking about him to me and said, "If Nayana had not come here (meaning to himself) and had his mind turned inwards to the Self, he would have certainly ended up in jail." Nayana had in his earlier years a predilection for political activity.

Aurobindo and the Mother recognized Ganapati Muni's extraordinary gifts. Kapali Śāstṛi once took the Muni to Aurobindo Ashram and everyone there was eager that he should stay. He was given a royal welcome and offered a house and all the necessary conveniences for him and his family. Someone back at Sri Ramanasramam informed Bhagavan of how Nayana was being enticed to stay in Aurobindo Ashram. While this person was describing it all to Bhagavan, he expressed the opinion that Nayana, indeed, might very well settle down there. Bhagavan looked at the man in surprise and said, "Nayana ? Settle down at Aurobindo Ashram? Impossible!"

Muruganar, like Ganapati Muni, was an inspired poet. It is said when one receives the gift of writing it is similar to taking a new birth. Muruganar was like that. His poetry is of a very high order. In his case, the gift became the master and he was the servant of it. The gift compelled him to write.

Learned Scholars

Many learned scholars and sannyasins would often visit Bhagavan and ask questions. Bhagavan's response to these visitors, and also to other visitors, was not always uniform. To some people he would give much attention, either by talking to them or pouring out his grace through a silent look; others he would stoically ignore. All these variations were not governed by status, wealth, or fame.

One morning a famous swami of Ahmedabad arrived at the ashram. I understood he had many wealthy disciples and was himself attired in a costly silk, ochre-colored cloth. He also had several pieces of luggage, which clearly indicated he was a man of some means. The swami came into the Guest House for Gentlemen and introduced himself to me. He wanted to know when he could see the Maharshi. I told him at 10 a.m. I would be going to the hall and he could accompany me and at that time I would introduce him to the Maharshi.

During that period, between 10 and 11 a.m. every morning in the Old Hall, Devaraja Mudaliar, Munagala Venkataramiah and I were going through Venkataramiah's English translation of a Tamiḷ scripture. Bhagavan would open and hold the Tamiḷ book in his hand and we would read the English translation for each verse. Then we would discuss it until we found it acceptable to Bhagavan.

The swami entered the hall with me at 10 a.m. and I introduced him to Bhagavan. He was fluent in Sanskrit and other languages, and also was well versed in all the scriptures. He inquired if he was allowed to ask a question. The consent was given and he asked Bhagavan if Ishwara, the personal God, actually existed. The Maharshi replied with one of his standard rejoinders: "We do not know about Ishwara or whether he exists or not. But what we do know is that we exist. Find out who that 'I' is that exists. That is all that is required."

The swami was not satisfied with this answer and continued to discuss the matter, quoting from various scriptures. Bhagavan then said, "If the scriptures say all this about it, why question me further?"

This also was not acceptable to the swami and he proceeded with more elucidation, at which point Bhagavan cut him off by turning to us and saying, "Come on. Let us begin our work." It is needless to say that the swami became quite annoyed and soon left the hall.

Later in the day I met him and he told me that my Maharshi doesn't seem to know very much. I simply replied, "Yes." And although this visitor was originally planning on staying for three days, he cut his visit short and left that very afternoon, without ever going back into the hall to see the Maharshi. Bhagavan later asked me what the swami said before leaving. When I told him, he simply smiled.

I remember when another similar incident occurred with a famous swami from Bombay, brought to the ashram by Mr. Bose. Although this swami too was well-known, had numerous disciples and was always given high honors wherever he went, in Bhagavan's presence he was just like everyone else: given no special seat, no special attention and made to sit on the floor with all the others.

When the swami had asked his first question, Bhagavan remained silent for a long time. He must have been wondering why there was no answer. Probably no one had ever, seemingly, ignored him like that before. The question was: "Which Avatar (incarnation) are you?" After sometime the Mauni (Srinivasa Rao) came into the hall and Bhagavan said to him, "He wants to know which Avatar I am. What can I say to him? Some people say I am this and some say I am that. I have nothing to say about it."

This was followed by a barrage of questions from the swami, who asked about Bhagavan's state of realization, about samadhi, the Bhakti school, etc. Bhagavan answered him very patiently, point by point. The swami listened and whether or not he was satisfied is hard for me to say. Before leaving the hall, the swami touched Bhagavan's couch, joined his palms in salutation and took leave.

In Day by Day with Bhagavan more conversations with this swami have been recorded. Mr. Bose reported that before the swami boarded his departing train in town he told him, "I have truly gained something from this visit to the Maharshi." Bhagavan also commented after his departure, "It will work." Whenever he made this observation we understood it to mean that the conversation the person had with Bhagavan will sink in and ultimately have positive effects.

One day, this same Mr. Bose came to the ashram in deep despair. His only son, a bright boy of twenty, had just died. A private meeting with Bhagavan was arranged between 12 and 2 in the afternoon. At one point during the interview, in a desperate and somewhat challenging tone, Mr. Bose asked, "What is God?" For such a long-standing devotee to ask this question looked incongruous.

Bhagavan kept silent for a while and then gently replied: "Your question itself contains the answer: What is, (is) God."

One should note that this was not merely a clever and well-thought-out answer. That may be the case with ordinary men. A Jnani's utterances are free from the intermediary action of the mind, which colors and often distorts the truth. Also, Bhagavan's silence before answering the question was evidently meant to prepare the questioner to receive the full impact of the answer.

Another incident comes to my mind when yet one more learned swami visited Bhagavan. He questioned Bhagavan in Sanskrit and Bhagavan, once again, patiently answered in Malayalam, the swami's mother tongue. As the session continued it became clear that this swami's sole intention was to defeat Bhagavan in argument. Eventually Bhagavan said, "Will you be satisfied if I issue you a certificate stating you have defeated me in the argument?" But even that did not silence the swami's impertinence.

Jagadish Śāstṛi, a Sanskrit pundit, was quietly listening to the proceedings. When he saw that the swami was incorrigible, he blurted out in Sanskrit, "He dushta bahirgachha," which means "O wicked man, get out!" I don't remember anyone ever making such an aggressive remark in the presence of Bhagavan. But it worked. The swami finally got the message and left the hall.

Bhagavan had no desire to argue or to prove anything to anyone. If people were not ready to accept his teaching, he would never try to force his views upon them. He left people free to believe whatever they wanted.

And his response to visitors was never influenced by status, wealth, or appearance. What was within the heart of the visitor reflected onto the clear mirror of Bhagavan's mind. His responses were automatic and directed to the needs of whomever he addressed. Those with genuine humility and childlike faith would attract his grace spontaneously. The garb of a sannyasi, of a householder, a man, child, or a woman, meant nothing before the pure, all-knowing gaze of Bhagavan.

Insincerity

When we were living with Bhagavan there was one thing we could never be: insincere. There was no way we could fool him on this account.

Once a group of influential devotees from Madras came up with a scheme to take Bhagavan away to Madras. In an attempt to execute this plan, a number of them arrived at the ashram and came into the hall. It wasn't long before they realized that Bhagavan would never consent to leave Ramanasramam, and eventually they left.

One old devotee was sitting in the corner of the hall quietly watching the whole drama unfold. He said nothing while the discussion was underway, though he was secretly in collusion with the group from Madras. After the group left, Bhagavan turned to one of his attendants and said, "Some people will sit quietly as if they have nothing to do with what is taking place before them. But on the contrary, they have everything to do with what is going on."

The old devotee questioned, "Bhagavan, are you testing me?"

Bhagavan simply remained silent. Any acts of insincerity were easily known to Bhagavan and he did not hesitate to point them out.

Foreigners and the English Language

I had seen many Western visitors come to the ashram after reading or hearing about the Maharshi. Out of all these foreigners, none had impressed me so much as Grant Duff. He was 70-years-old, tall, lean, graceful in his movements, and when he spoke his words were clear and soft, originating from a deep sincerity.

On his first visit, I remember him asking if he could hear the Vedas recited. A chair for him was placed in the hall opposite Bhagavan's couch, while the priests chanted. At the conclusion of the parayana he looked at Bhagavan and said with deep feeling, "Magnificent!". Bhagavan also openly spoke of his virtues. Rarely had I heard Bhagavan speak about anyone like that.

Grant Duff studied Sanskrit for six months in Ootacamund. He loved the language and he loved Bhagavan. No one has written in English about Bhagavan as he has, as can be seen in the preface to Ramana Gita.

Duncan Greenlees, whom I knew well, was another Englishman attracted to Bhagavan. He had an M.A. degree from Oxford University. Because of the many plans and projects he wanted to carry out in India, he was unable to stay with Bhagavan for any length of time. He was a Theosophist and had been commissioned by the Theosophical Society to write a fifteen volume History of Religion. Besides this, he had grandiose schemes to open many schools in India, but as fate had it, he was unable to accomplish any of his great designs before his death.

Bhagavan was familiar with, and had respect for, the classical English works. He had read many English books and would daily read an English newspaper. W.Y. Evans-Wentz had given Bhagavan copies of his published books, and of these books Bhagavan liked best Tibet's Great Yogi, Milarepa. He once requested me to read it.

Although he read and understood English quite well, he rarely spoke it. If people spoke English to him with clear diction and pronunciation he would not have much trouble understanding them. Once he said to me, "I couldn't understand a word Chadwick said." Which shows he did fail to understand English at times if not spoken clearly.

Bhagavan was once walking to Palakothu when the American engineer Guy Haig was standing directly in his path, apparently waiting to ask something. I was at the moment approaching from behind, but before I reached there, Haig had asked, "Can I help others after the attainment of Self-realization?"

To this Bhagavan replied in concise English, "After the realization of the Self there will be no others to help."

The State of a Jnani

Bhagavan once remarked, referring to himself, "In this state it is as difficult to think a thought as it is for those in bondage to be without thoughts." I also remember him telling us, "You ask me questions and I reply and talk to you. If I do not speak or do anything, I am automatically drawn within, and where I am I do not know."

This state is difficult for us to comprehend. Once during the winter months Bhagavan was sitting on his couch and, at one point, while picking up a shawl and wrapping it around himself, remarked, "They say I gained realization in twenty-eight minutes, or a half an hour. How can they say that? It took just a moment. But why even a moment? Where is the question of time at all?"

Then I asked Bhagavan if there was ever any change in his realization after his first experience in Madurai. He said, "No. If there is a change, it is not realization."

How he managed to remain in that unbroken state of Universal Awareness and still function in a limited, physical form remains a mystery. We cannot understand that state. And in spite of his exalted state, he interacted with us at our level. He took considerable interest in the operation of the ashram and the accommodation of visitors. This, no doubt, was a simple act of grace on his part, for what need did he have for all of this?

Once a princely family of India was visiting the ashram. It was commonly known that in spite of their high social position they were having financial difficulties. After they had visited for a few days and were preparing to leave, Bhagavan sent word to the office that no one should ask them to donate anything to the ashram.

On another occasion there was a French visitor named Jean Herbert, who had written several books on India, its holy men, and ashrams, etc. I saw him while he was on his second visit to the ashram. During this visit he requested the publication rights of all of the ashram literature, as he planned on using this material in his books. The ashram authorities were at first enthusiastic about books being published in the West on Bhagavan and his teachings. I told Bhagavan that Jean Herbert also requested the same permission from Aurobindo Ashram, but they decided not to give it. Perhaps they felt he would exploit Aurobindo's writings. When I had told Bhagavan this, he requested me to go to the office and explain it to them. I did, and the permission was withheld.