As I Saw Him - No.8

A. Devaraja Mudaliar had a unique, innate ability to associate with the Maharshi in an entirely natural manner, while yet maintaining complete faith and devotion to him. This resulted in an intimate relationship and frank dialogues on many subjects, including the practical application of the Maharshi's teachings.

The rare devotion Devaraja Mudaliar developed for the Maharshi eventually compelled him to leave his home and profession and settle down in Sri Ramanasramam in 1942. His four years of tenancy at the Ashrama secured for posterity invaluable records in the form of a diary, subsequently published as Day By Day with Bhagavan. Later, his written reminiscences formed the book entitled My Recollections, which is the source for the following article.

Devaraja Mudaliar, at the ripe age of 85, was absorbed in his Master in 1972.

The earliest recollection I have of Bhagavan dates back to 1900. Along with some of my relations, I went to Tiruvannamalai for the Deepam festival. Even as early as that, the crowds that came for Deepa darshan used to visit our Bhagavan, then popularly known as Brahmana Swami.

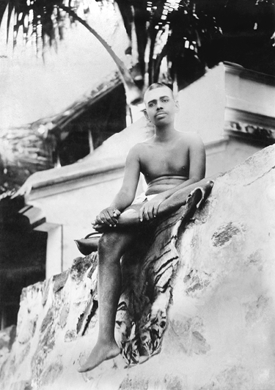

I did not visit him again until 1914, two years after I came to Chittoor and settled down there to practise as a lawyer. Kuppuswami Mudaliar accompanied me on my visit. We arrived at about 2 o'clock in the afternoon and found Bhagavan sitting on the parapet wall outside Virupakshi Cave. So far I can remember there was no one else there at that time. There were only a few monkeys near Bhagavan, and he started telling me about them, their ways, their government, kings, queens, etc. I stayed nearly two hours and the whole time was spent in listening to these stories about monkeys. I was still a young man and did not take seriously to the spiritual side of life, so I did not ask Bhagavan for any spiritual guidance. I was satisfied with having seen him and talked to him.

It was made possible for me to visit Bhagavan again about the end of 1922. By this time Bhagavan's mother had attained Mahasamadhi and Bhagavan had come to live near the mother's samadhi (grave) at the foot of the hill where Sri Ramanasramam now stands. There was a small thatched shed housing the samadhi, where the temple now stands, and to the north of the samadhi was a narrow pial, or raised floor, on which Bhagavan used to sit or lie down.

I told Bhagavan that, though I went to temples like other people, they did not much appeal to me and asked Bhagavan what he would advise me to do. He replied: "That does not matter. Think of God as being in your heart and meditate on God that way. That will be enough."

The end of 1933 saw my first long stay of nearly a week at Bhagavan's feet and his presence was such a balm to my stricken heart that from that visit dates my intimate and close association with him.

It is said that man's adversity is God's opportunity. Bhagavan proved a great solace to me when I lost my wife in 1933 (I was then 47). So naturally, when the next misfortune came, in 1935, I threw myself even more completely on Bhagavan, going to him as often as possible and basking in his presence.

I lost my job as Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor which I had held for fifteen years (that is for five successive terms). In my then circumstances, this was a great misfortune, and it was a serious problem with me how I was going to make both ends meet after losing a steady, assured income of about Rs. 6,000 a year to which I had been accustomed for fifteen years. I mention the gravity of this crisis only to indicate that it drove me to lean more and more upon Bhagavan.

I decided about 1939, that I would give up practice completely in 1941, wind up my establishment at Chittoor and go and live with Bhagavan at the Ashrama for the rest of my life. I asked and received permission to build a one-room cottage inside the Ashrama premises. Such permission was rarely given, in fact it was given only to two others, namely, Major Chadwick and Yogi Ramaiah. The room was ready for me by June 1940.

It was about the end of August 1942, I think, that I went to live at Sri Ramanasramam as a permanent inmate. However, for some little time more, I had to go to Chittoor now and then in connection with remaining professional work or my private affairs.

When I had resided in the Ashrama I gradually made a routine to sing for about half an hour between 10 and 11 in the morning, that is for the last twenty minutes or half hour between when Bhagavan had finished going through the second mail and when the gong went for lunch. Bhagavan saw that this was my line of approach and was doing me good. Therefore he took care, by the silent working of his grace, that nobody interfered with it.

In the early days Bhagavan encouraged me whenever I was singing with deep feeling. He would have such a look on his face, with his radiant eyes directed towards me, that I would be held spellbound, and not infrequently, at some especially moving words in the songs, tears would come and I would be obliged to stop reciting for one or two minutes. Bhagavan told me that such weeping is good, quoting from Tiruvācakam: "By crying for You (God), one can get you."

This seems an appropriate place for referring to another well known characteristic of Bhagavan. To those who have only a very superficial knowledge of him or his works, it might seem that he was a cold, relentlessly logical, unemotional Jnani, far removed from the Bhakta who melts into tears in contemplation of God's grace and love. But to those who had any real experience of Bhagavan and his ways, and works, it was clear that he was as much a Bhakta as a Jnani. Often he has told us that only a true Bhakta can be a true Jnani and that only a true Jnani can be a true Bhakta. The complete extinction of the ego is the end attained either in jnana or bhakti.

When touching songs were recited or read out before him, or when he himself was reading out to us poems or passages from the lives or works of famous saints, he would be moved to tears and would find it impossible to restrain them. He would be reading out and explaining some passage and when he came to a very moving part he would get so choked with emotion that he could not continue but would lay aside the book.[1]

Before taking leave of this topic, I must remark that it was not only any moving song about God that had this effect on him but anything grand, magnanimous, noble or generous moved him as few people could be moved. I was often reminded of the sentence, "The finest minds, like the finest metals, dissolve the easiest."

Many times I complained to Bhagavan that I was not making any appreciable progress, bemoaning the persistence of desires. Bhagavan replied making light of my trouble: "It will all go, all in time. You need not worry. The more dhyana (meditation) one performs the more will these desires fall off."

On other occasions when I complained that I was not improving, Bhagavan simply replied, "How do you know?"

Bhagavan, from what little I know of him, was not one who believed in forcing the pace. On the contrary, he gave me the impression that he felt it was not proper and was not for our real good, that he should interfere and do violence to our nature or Prakriti by hurrying us at a faster pace than we are built for, even towards realization.

Once I had planned to carry out something in conjunction with someone else who was then staying permanently near the Ashrama. Neither at the time, nor even now according to my lights, was there anything so very objectionable about what we had planned. But suddenly one afternoon, out of a trivial and altogether inadequate circumstance, a quarrel arose between us and what we intended was called off. The next morning I happened to be sitting very near Bhagavan's couch, at his feet, and Bhagavan, apropos of nothing in particular and with an expression of love and pity, turned to me and said in a low voice: "We should not make elaborate plans to get anything. I don't object to your enjoying what comes your way of its own accord."

Then I knew beyond all doubt that it was Bhagavan who, foreseeing some harm for me in what I had planned, brought about the sudden and unexpected quarrel the previous afternoon and aborted our plans. When Bhagavan told me this, I asked him, "Does that mean that if a thing comes to me without any planning or working for it and I enjoy it, there will be no bad consequences from it?"

Bhagavan then hastened to add: "It is not so," and explained: "Every act must have its consequences. If anything comes your way, by reason of prarabdha (destiny based on the balance sheet of past lives) you can't help it. If you take what comes, without any special attachment and without any desire for more of it or for a repetition of it, it will not harm you by leading to further births. On the other hand, if you enjoy it with great attachment and naturally desire for more of it, that is bound to lead to more and more births."

About work, Bhagavan used to say: "No sort of work is a hindrance on the spiritual path. It is the notion 'I am the doer' that is the hindrance. If you get rid of that by enquiring and finding out who is this 'I', then work will be no hindrance since you will be doing it without the ego sense that you are the doer and without any attachment to the fruits of your work. Work will go on even more efficiently than before; but you can always be in your own, natural, permanent state of peace and bliss. Further, one should not worry about whether one should engage in work or give it up. If work is what is ordained for one, one will not escape it, however much one may try. On the other hand, if no work is ordained for one, one will not obtain work however much one wishes to strive for it."

One summer afternoon I was sitting opposite Bhagavan in the Old Hall, with a fan in my hand and said to him: "I can understand that the outstanding events in a man's life, such as his country, nationality, family, career or profession, marriage, death, etc., are all predestined by his karma, but can it be that all the details of his life, down to the minutest, have already been determined? Now, for instance, I put this fan that is in my hand down on the floor here. Can it be that it was already decided that on such and such a day, at such and a such an hour, I shall move the fan like this and put it down here?"

Bhagavan replied, "Certainly." He continued: "Whatever this body is to do and whatever experiences it is to pass through was already decided when it came into existence."

Thereupon I naturally exclaimed: "What becomes then of man's freedom and responsibility for his actions?"

Bhagavan explained: "The only freedom man has is to strive for and acquire the jnana which will enable him not to identify himself with the body. The body will go through the actions rendered inevitable by prarabdha and a man is free either to identify himself with the body and be attached to the fruits of its actions, or to be detached from it and be a mere witness of its activities."

It may be well to remind ourselves that Bhagavan has given his classic answer to the age-old question "Can free will conquer fate?" as follows in his Forty Verses: "Such questions worry only those who have not found the source of both free will and fate. Those who have found this source have left all such discussions behind."

A lady Principal asked Bhagavan whether it was not better for people to work and do something for the betterment of the world than to sit in contemplation, aloof from the world, seeking for their own salvation. This was not by any means a new question and Bhagavan had given a very clear answer to it which has already been published in the Maharshi's Gospel. In brief, it is that one Jnani by his Self-realization is doing much more for the world than all social workers put together and that his silence is more eloquent and effective than the words of orators and writers advocating any courses for man. On this occasion, however, Bhagavan remained silent. When the lady found that Bhagavan did not answer, she went on speaking for some ten minutes. Even then Bhagavan remained silent. The lady and her sister then left in chagrin.

After they had left Bhagavan said to me: "It is no use telling them anything. The only result would be that it would be published in the papers that such and such are the views of so and so and there will be endless dispute. The best thing is to keep quiet."

His view on the attempts, however well intentioned, by idealistic reformers, whether socialist or communist or whatever label they may wear, to make all people equally well-placed in life can be epitomized as follows: "There never was and never will be a time when all are equally happy or rich or wise or healthy. In fact none of these terms has any meaning except in so far as the opposite to it exists. But that does not mean that when you come across anyone who is less happy or more miserable than yourself, you are not to be moved to compassion or to seek to relieve him as best you can. On the contrary, you must love all and help all, since only in that way can you help yourself. When you seek to reduce the suffering of any fellow-man or fellow-creature, whether your efforts do succeed or not, you are yourself evolving spiritually thereby, especially if such service is rendered disinterestedly, not with the egoistic feeling 'I am doing this', but in the spirit 'God is making me the channel of this service; He is the doer and I the instrument'." On two successive days, in answer to questions from visitors, Bhagavan said in effect what I have summarised above.

Most of the time I lived with Bhagavan, I used to feel peaceful and absolutely free from care. That, as many can testify, was the outstanding effect of his presence. Nevertheless, it did occasionally happen that something disturbed the peace and happiness for a while. On one such occasion I asked Bhagavan: "Why do such interruptions come? Does it mean that we have ceased to have Bhagavan's grace then?"

With what graciousness did Bhagavan reply: "You crazy fellow! The trouble or want of peace comes only because of grace."

On other occasions also Bhagavan has similarly told me: "You people are glad and grateful to God when things you regard as good come to you. That is right, but you should be equally grateful when things you regard as bad come to you. That is where you fail."

Here I must say the only method I have adopted to achieve liberation or Self-realization is simply to throw myself on Bhagavan, to surrender to him as completely as lies in my power, and to leave everything else to him. And Bhagavan's teaching, the last I ever got from him before he attained Mahasamadhi, was just this: "Your business is simply to surrender and leave everything to me. If one really surrenders completely, there is no room for him to complain that the Guru has not done this or that."

To me and a number of other devotees of Bhagavan, he was God and all in all. We felt as Saint Arunagirinathar felt when he declared to Lord Muruga:

"I rely on none except you and will follow none except you." I have often sung this song before Bhagavan, altering the last two lines in such a way that they would refer to Bhagavan, instead of to Muruga. But about whomsoever we sang, whichever temple we visited, or whatever image we worshipped our homage always went to Bhagavan.Mother Azhagammal, Her Final Day

Seventy years ago this month, on May 19, 1922, the Mother of the Maharshi breathed her last with her son sitting by her side. She prayed it would happen like this. The marvelous story of how the Maharshi guided her soul to the final shore of emancipation during her last moments is related here by, perhaps, the only living survivor who witnessed it, Sri Kunju Swami. Also, he goes on to describe in detail how the body was interred near the Pali Tirtham.

On that last day from 5:00 a. m. there was a premonition that this was Mother's final day. Bhagavan sat by her side and put one hand on her chest and the other on her head. He was advising everyone to go and eat, because if she died it was considered unclean by orthodox people to eat in a house where a death occurred. Some of the orthodox ones among us went and ate. But others who felt particularly close to Bhagavan didn't think about leaving him to go and eat.

Bhagavan continued to sit by Mother's side and kept his hands on her.

Different expressions of joy and sorrow were passing over her face. Bhagavan was commenting, "Is Mother in this world? No. She is in different worlds going through various births and the consequent experiences."

When her passing seemed imminent, people like Ganapati Muni, T.K.Sundaresa Iyer, and others decided to recite from the Vedas. On the other side, Saranāgatī Ramaswami and a Punjabi gentleman started reciting Rama Japa. Without any forethought we joined in with the singing of Aksharamanamalai and Arunachala Siva.

Amidst this loud singing and reciting of various scriptures, Mother left the body. Still Bhagavan continued to keep his hands on her heart and head. We wondered why he was still seated like that. Then he explained: "When Palaniswami was breathing his last, I did the same thing. I thought the soul had subsided in the heart and removed my hands. He opened his eyes and the life force left through the eyes. So this time, to be certain, I am keeping the hands on longer than needed." I learned this important secret from Bhagavan that day.

He then got up and we all ate. After eating we gathered again near the body without any feeling of pollution.

Ganapati Muni had raised the question about the possibility of a woman attaining the state of Realization in Ramana Gita. Bhagavan said that the state of Realization does not relate to the form of the gross body. So we all felt satisfied that Mother had attained liberation and we were happy. Happier, indeed, because we saw that Mother's face and body were now radiating such lustre and light.

Since Bhagavan had given her mukti, and her whole body and face were shining, it was decided that the body should be given a ceremonial burial, instead of the customary burning for Brahmin widows.

We then joyfully decorated the body with kumkum, malas and flowers. After deliberation we decided that Mother's body should be buried near the Pali Tirtham. We decided to keep this decision secret because we knew if this news spreads there would be an unimaginable crowd gathered for the samadhi (funeral).

We decided to bring the body down to the hill before 5:00 a.m. In the meantime, Ramakrishna Swami and Perumal Swami went to town and brought to the burial site two or three cart loads of funeral supplies - cement, camphor, vibhuti, etc.

I still remember that the day before Mother's Mahasamadhi, Ramakrishna Swami and I had gone up the hill and found many bamboo trees and brought back a good number of bamboo sticks to Skandasramam. It was these sticks that were tied together and used to carry Mother's body down to Pali Tirtham.

I was instructed to remain at Skandasramam because telegrams had been sent to relatives in Tiruchuzhi and other places and they were expected to arrive at Skandasramam that morning.

The body was kept under the Asavastha tree and Bhagavan, along with other devotees sat near it. By 7:00 or 7:30 a.m. relatives from Tiruchuzhi and other places arrived and I brought them all down to Pali Tirtham. By this time the whole town heard the news and had come there. Many shopkeepers arrived with supplies of bananas, camphor, etc., pundits were reciting scriptures and Bhagavan sat majestically alongside the body. It looked as if we were in a temple.

There was much wild cactus at this site, and while some of us were removing it, Perumal Swami dug the pit and constructed the samadhi inside of it. About 10:30 or 11:00 a.m. everything was ready.

Bhagavan had already marked the passages in Tirumandiram, a text written by the great saint Tiruvarul explaining how a Jnani's body is to be interned. Accordingly, Mother's body was carried to the samadhi pit, placed inside, and Bhagavan poured on the body a large amount of vibhuti. Others followed by adding camphor, sandalwood, etc., in full accordance with saint Tiruvarul's injunctions. The samadhi was then closed, some stones were placed over it, and a small shrine was constructed. It was, indeed, a glorious sight.

After this ceremony we all went to Palakothu where arrangements were made to feed some 200 people. Bhagavan started walking towards Palakothu with the others. Leading the procession was a group of musicians with drums and horns playing the nadaswaram. The distance to Palakothu was only one or two hundred yards, but Bhagavan walked so slowly and majestically it took two hours to cover the distance. It was a sight even for celestial beings to see.Pranayama and Self-Enquiry

To the visitor who pursued the question about pranayama (breath contol), Bhagavan said, "The aim is to make the mind one-pointed. For that pranayama is a help, a means. Not only for dhyana, but in every case where we have to make the mind one-pointed - it may be even for a purely secular or material purpose - it is good to make pranayama and then start the work."

"Those who have not the mental strength to concentrate or control their mind and direct it on the quest are advised to watch their breathing, since such watching will naturally and as a matter of course lead to cessation of thought and bring the mind under control. Breath and mind arise from the same place and when one of them is controlled, the other is also controlled. As a matter of fact in the quest method - which is more correctly 'Whence am I?' and not merely 'Who am I?' - we are not simply trying to eliminate saying 'We are not the body, not the senses and so on,' to reach what remains as the ultimate reality, but we are trying to find whence the 'I' thought for the ego arises within us. The method contains within it, though implicitly and not expressly, the watching of the breath. When we watch wherefrom the 'I' thought, the root of all thoughts, springs, we are necessarily watching the source of the breath also, as the 'I' thought and the breath arise from the same source. Retaining breath, etc., is more violent and may be harmful in some cases, e.g., when there is no proper Guru to guide the sadhaka at every step and stage. But merely watching the breath is easy and involves no risk."

Films from Sri Ramanasramam

Part 6

We continue with the description of the Golden Jubilee film taken on Tuesday, September 1, 1946, by the Indian Information Bureau. This film was later distributed to cinema houses around the country. During this scene (described in our January/February 1992 issue) we hear the following narration in typical British accent:

"...Ashram of Ramana at Arunachala drew crowds of devotees on September the First to mark the completion of fifty years when Ramana first set foot on the sacred soil of this historic mountain shrine. From far and near they flocked the darshan of the holy sage, who by the severest austerities and profound contemplation has attained spiritual wisdom and serenity unique in the country. Thousands draw comfort by his mere presence, for he neither preaches nor blames, setting all at ease who come to him by the essential goodness he radiates to all around - a good man in a troubled world."

The beginning of the narration has been cut off, perhaps lost, but what remains is sufficient to recreate what many thousands of viewers saw throughout India.

At the end of this newsreel we see the most detailed frontal view of the Maharshi's face on film. He is wearing a short beard, exhibits a calm and distant look, and faces directly into the camera for twelve seconds. His head, which is shaking slightly, nearly takes up all the screen. The last few of these twelve seconds were stilled by an earlier film editor.

Then something interesting takes place. Suddenly we are looking at the Maharshi's back, while a small group of prominent devotees surround him. They also have their backs turned to the movie camera. This is quite unusual, though the reason is soon noticed. Bhagavan is facing a large crowd of devotees and in the front of this crowd, with tripod and camera, stands Dr.T.N.Krishnaswami focusing in on his favorite subject - the Maharshi. Filmed from behind and photographed from the front, Bhagavan displays a typically indifferent but gracious attitude.

We must mention here, that Dr.T.N.Krishnaswami was the ordained Ashrama photographer and is responsible for many of the hundreds of photos we have of the Maharshi today. As a young man he first came to Tiruvannamalai in 1930 with his new camera to take photos of the grand Arunachala Temple. While at the temple, someone mentioned that he should go a little distance down the road and take photos of the sage living there. He did. The Maharshi cordially consented, and Dr.T.N.K., as he is often referred to in books, became an ardent lifelong devotee - a devotee with a camera. The walls of his house in Madras (he died in 1975), where his son now lives, are still lined with large framed photos of his Master.

We now come to a two minute 8mm color film taken by K.K.Nambiar. In his book, The Guiding Presence of Sri Ramana, he mentions the details relating to this film. In 1946 the State of Madras sent him abroad to learn certain engineering procedures. Before leaving New York he bought a 8mm color movie camera with the sole purpose of making a film at Sri Ramanasramam, which he did upon his return in February of 1947. After this, K.K.Nambiar filmed the Maharshi often and is responsible for more than half of all the films that we now have. He rose to the top of his profession and was able to assist the Ashrama in many capacities. As both an eminent and active devotee, we are deeply indebted to him.

And although Mr.Nambiar readily handed over all his other films to the Ashrama, he was reluctant to hand over this first film he took of Bhagavan in 1947. In fact, he never did: only after he passed away did his son give it to the Ashrama in February of 1990. Mr.Nambiar died in 1986.

A clue to why Mr.Nambiar withheld this particular reel is revealed from what his kind wife recently told us. She said that as he lay in bed during his final days, he would often reach over to the projector at his bedside, switch it on and view this film again and again.

While watching this film, and seeing the special indulgence granted to the Nambiars by Bhagavan, we can easily understand Mr.Nambiar's attachment to the film and the emotion it must have evoked in him.

[1]

...when he was reading and explaining some incidents in

Sundara Murthi Nayanar’s

life in connection with the

sacred history of Tiruchuzhi in the Sthala Purāṇam and also

when he was reading out

Thayumanavar’s

works and came to the 24th verse:

Regarding earth and heavens as you and drawing your portrait on the page of my thoughts, looking into that picture again and again I cry out, ‘Oh, my Master and Beloved, won’t you come and embrace myself regarding myself as you?’ Unable to perceive anything further, my heart grieves like those who are afflicted and tears gush forth from my eyes and I stand like those lost in ecstasy.